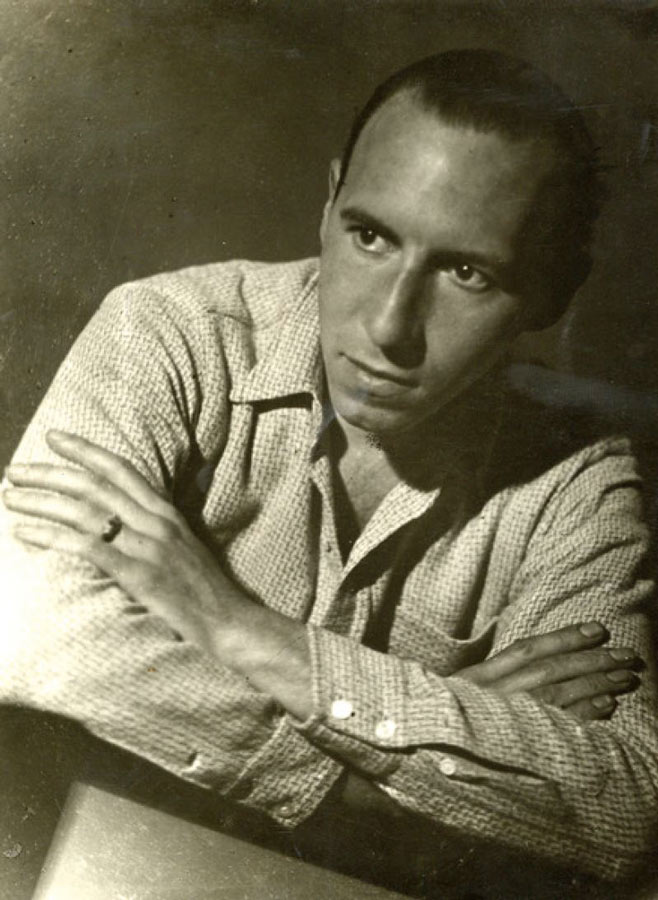

THE ARTIST

1901

childhood

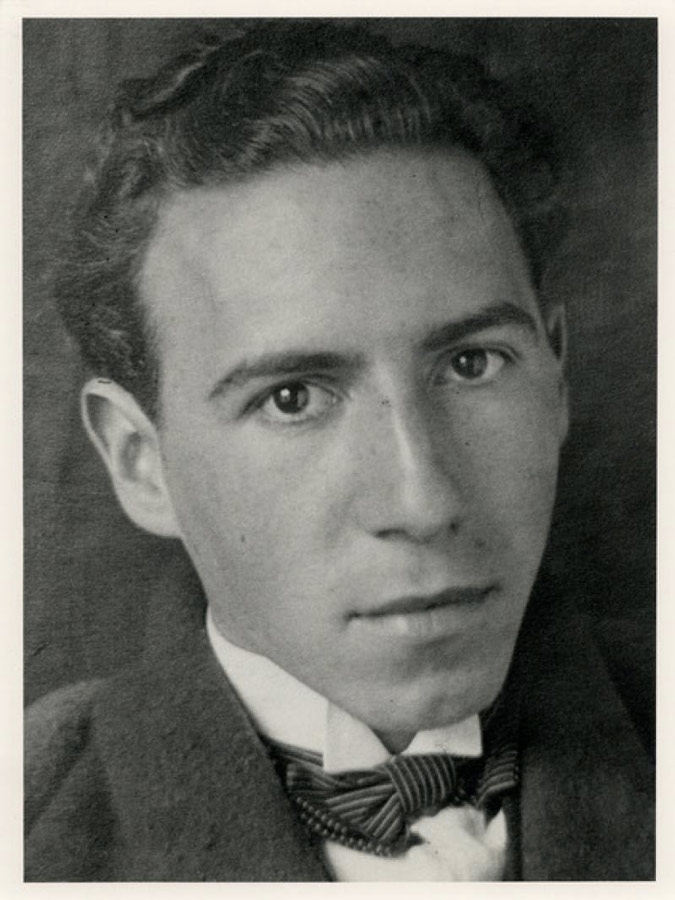

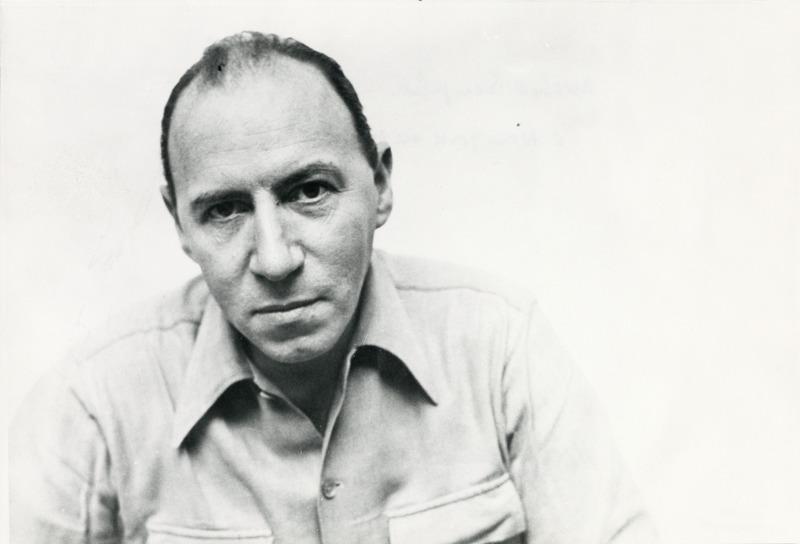

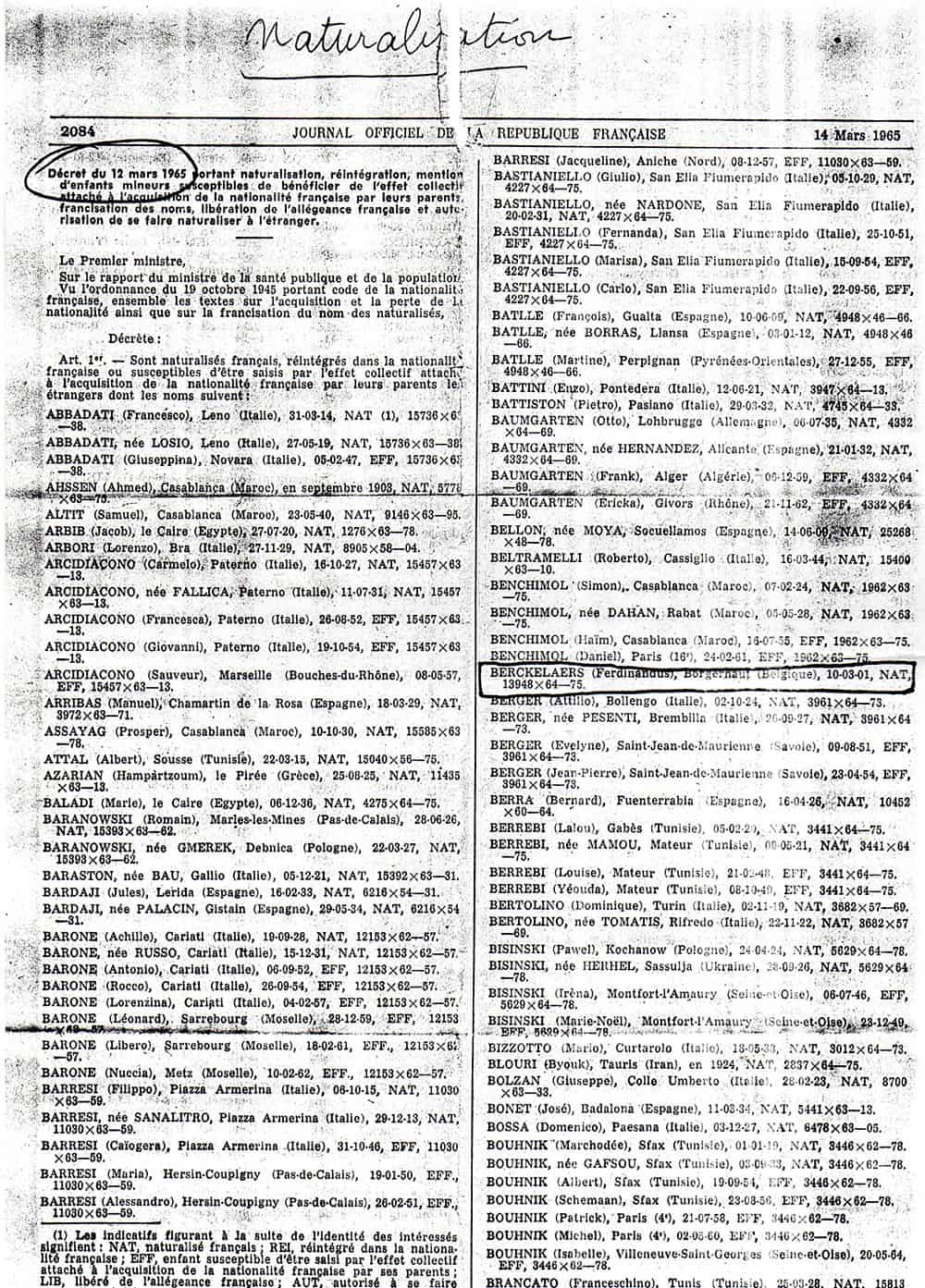

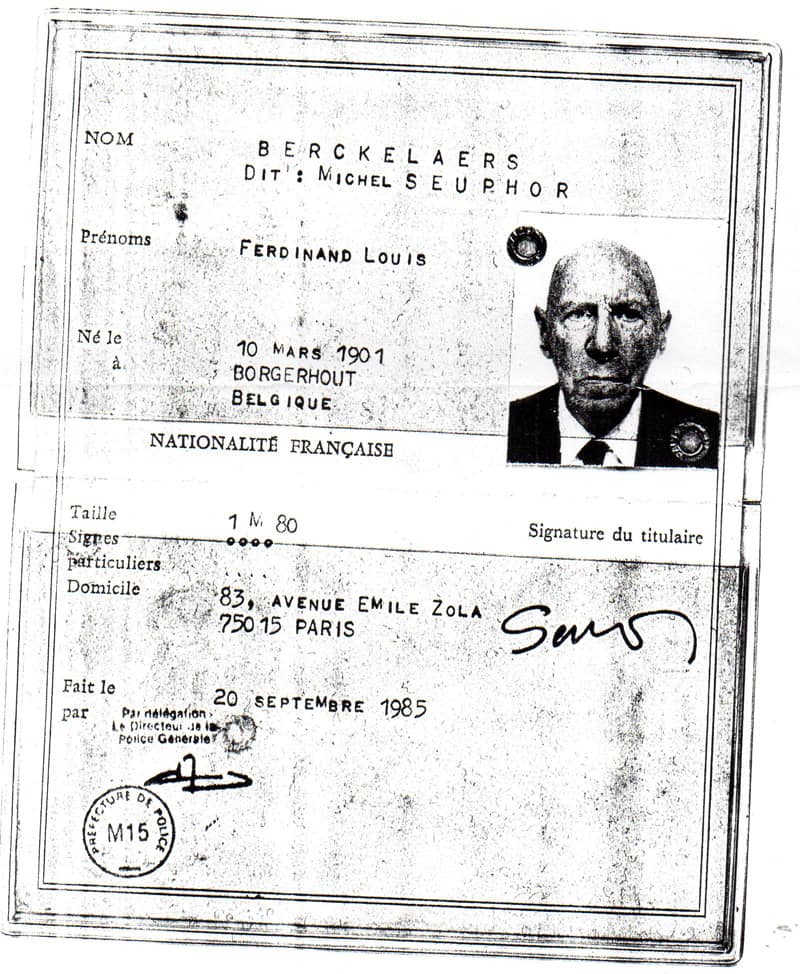

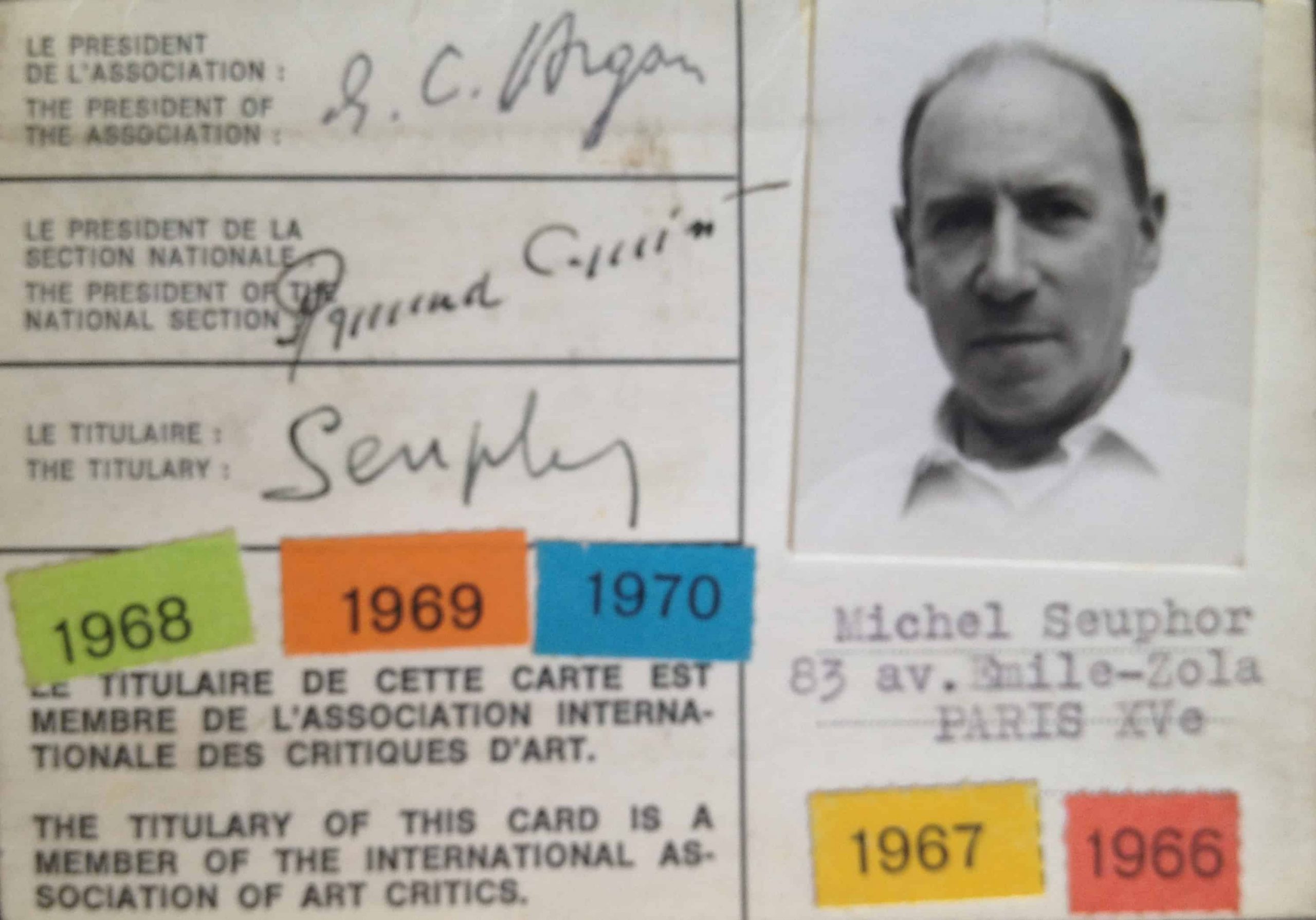

Fernand-Louis Berckelaers was born on March 10, 1901 in Borgerhout, a town near Antwerp in Flemish Belgium. His father died of tuberculosis when he was 9 years old. His mother was educated in her youth as a French-speaking bourgeois. She was avidly interested in art and culture. She liked to go the opera, the theater, and concerts. She took her son to the circus. Her personal library was very rich and young Fernand devoured its contents as soon as he could read. An only child, often left to his own devices, he developed his creativity through play and benefited from the tenderness and attention of his grandmother and the young maids who looked after him. These female figures surrounded him with a language bath where Flemish alternated daily with French.

His mother remarried in 1912 and gave birth to two little girls, Gabrielle and Madeleine. Seuphor always showed a great tenderness of feeling for his young sisters.

THE ARTIST

1901

childhood

Fernand-Louis Berckelaers was born on March 10, 1901 in Borgerhout, a town near Antwerp in Flemish Belgium. His father died of tuberculosis when he was 9 years old. His mother was educated in her youth as a French-speaking bourgeois. She was avidly interested in art and culture. She liked to go the opera, the theater, and concerts. She took her son to the circus. Her personal library was very rich and young Fernand devoured its contents as soon as he could read. An only child, often left to his own devices, he developed his creativity through play and benefited from the tenderness and attention of his grandmother and the young maids who looked after him. These female figures surrounded him with a language bath where Flemish alternated daily with French.

His mother remarried in 1912 and gave birth to two little girls, Gabrielle and Madeleine. Seuphor always showed a great tenderness of feeling for his young sisters.

•

Marriage of Eugène Berckelaers and Caroline Marien, parents of Fernand Berckelaers, late 1890s

•

Seuphor with his mother around 1904

•

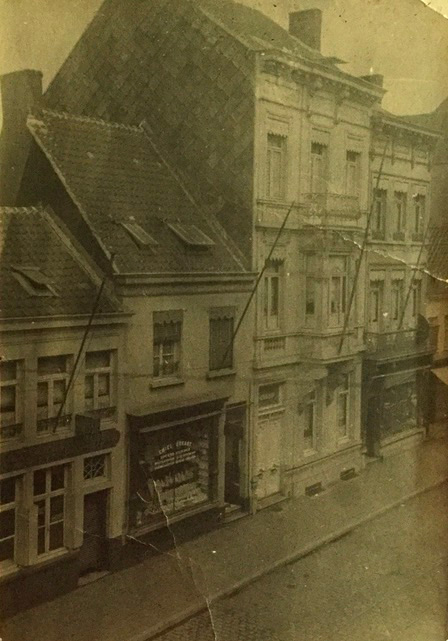

Family house in Turnhoutslaan, Antwerp-Borgerhout,

bombed during the second world war

1910

the college

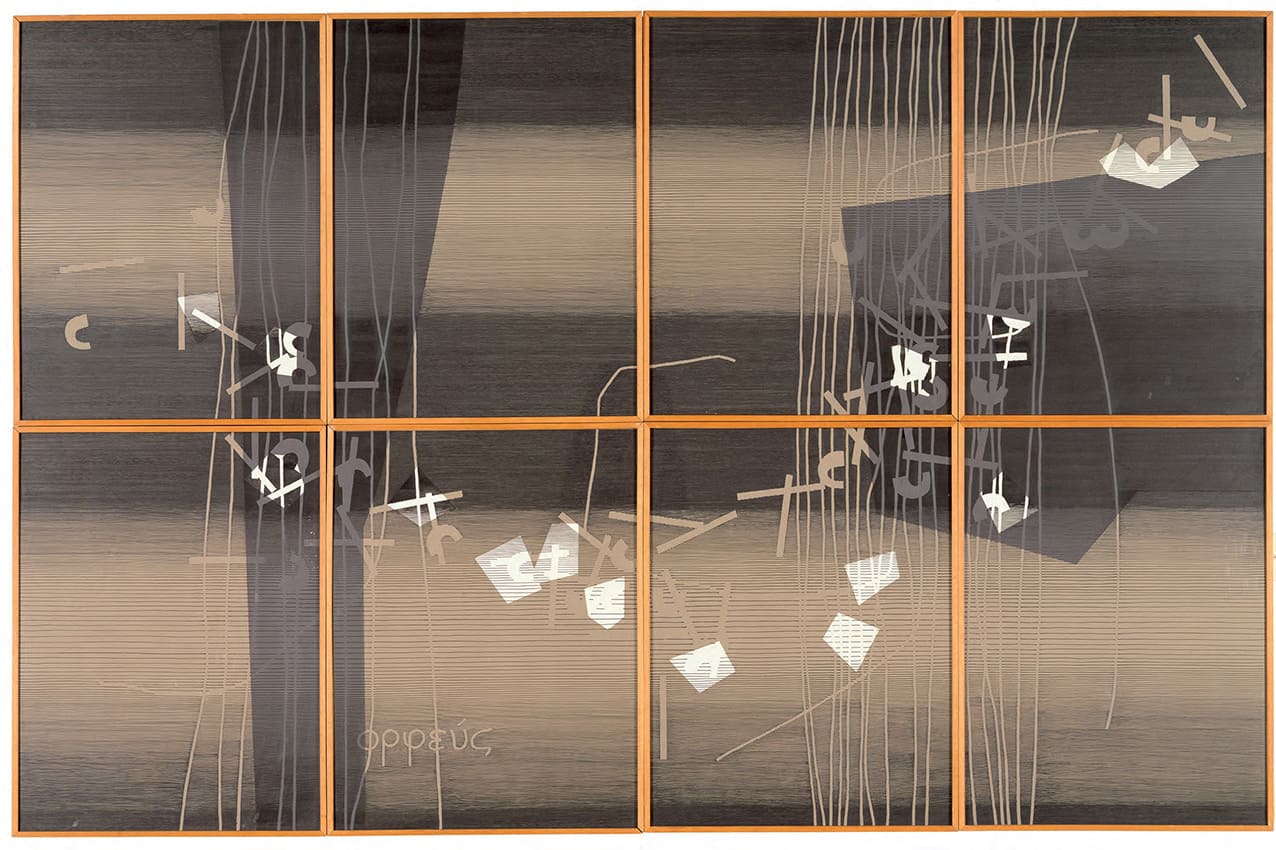

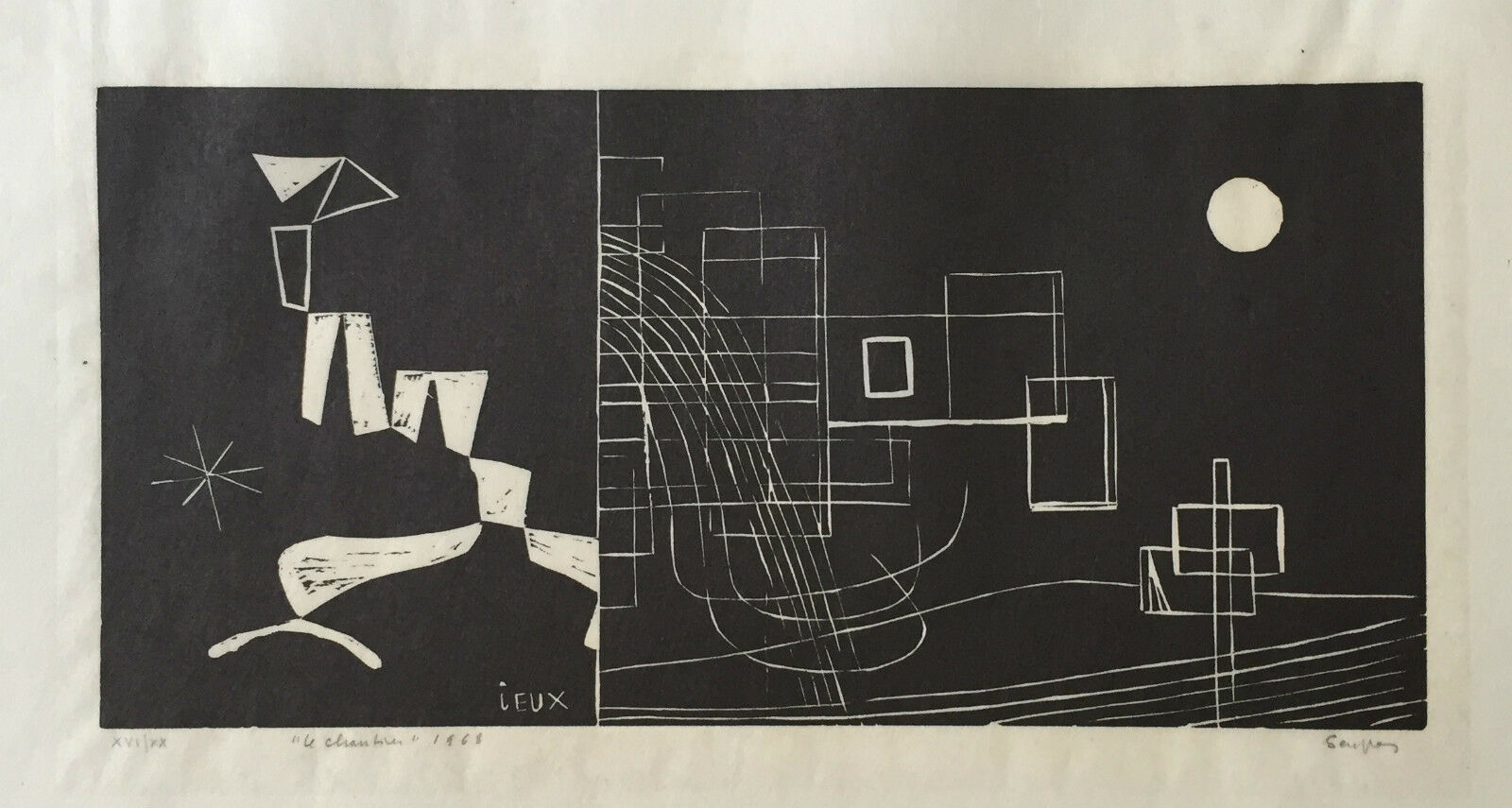

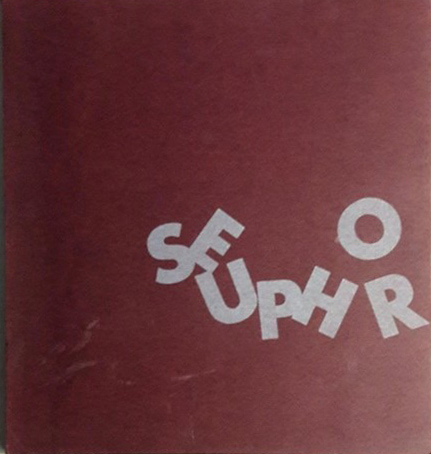

In 1910, Fernand entered the Jesuit College of Antwerp to pursue Greco-Latin studies in French. He would keep only painful memories from these years. Very early on, he came up against the rigidity of the fathers, and later endured their hostility when he committed to the Flemish movement. In a clandestine leaflet against them in 1917, he used, for the first time, the pseudonym Seuphor, an anagram of Orpheus taken from the title of a book by Salomon Reinach that he had in front of him.

“It was not thought out, simply because these letters were there, in large characters, white on mauve (…) But the name imposed itself little by little and, finally, remained. That day I had entered, with a light step, into another soul. (Le jeu de je, 1976).

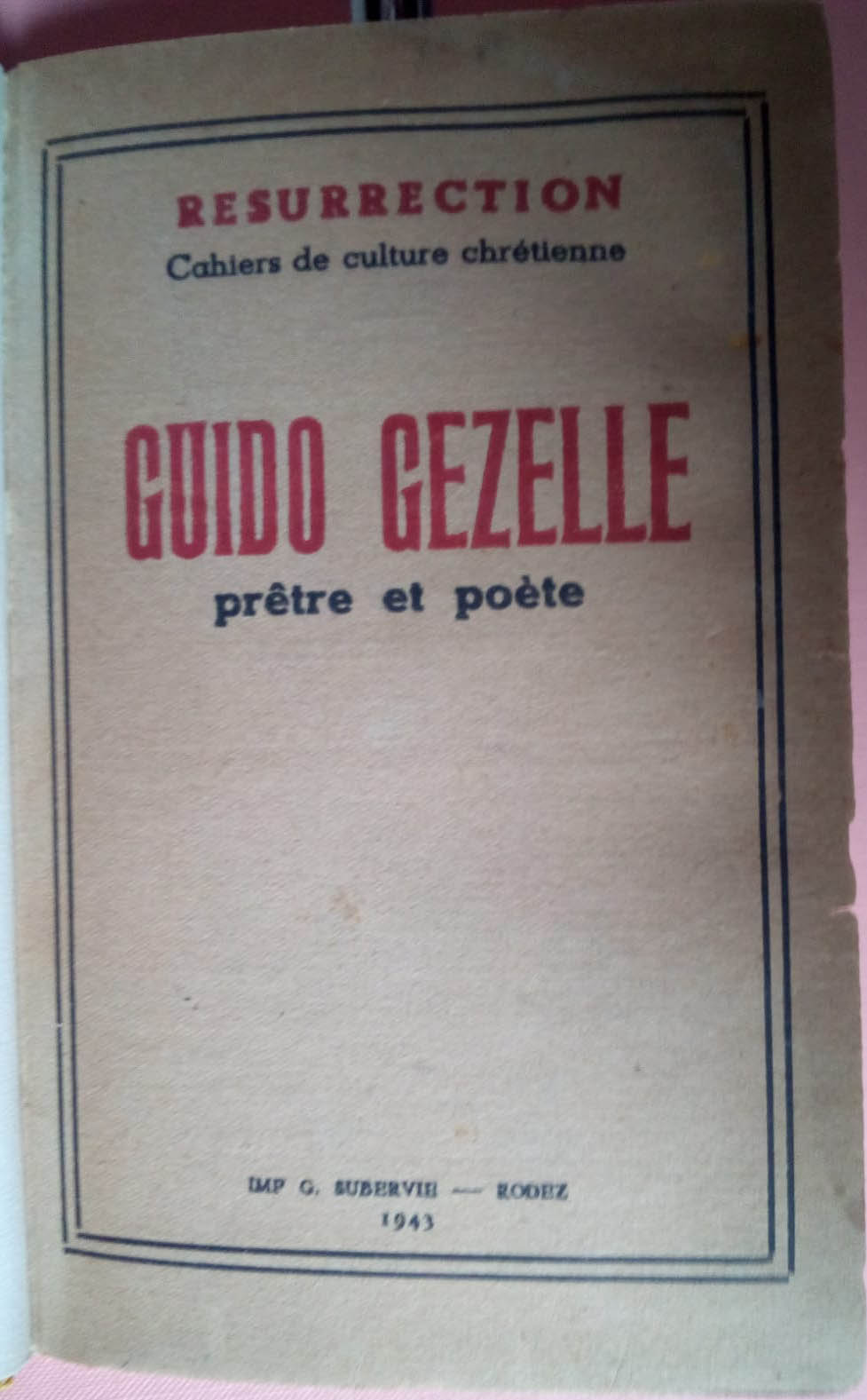

It is also at the college that he felt his first deep poetic emotion when he disovered the works of the Flemish poet Guido Gezelle, introduced by his young professor of Flemish, the father De Clipelle.

“Gezelle never left me. He has been the companion, both peaceful and exhilarating, of my long life.” (Le jeu de je, 1976).

In the end, he decided to terminate his studies at the college in 1918. Taking this freedom gave him paradoxically the taste and the absolute necessity of studying, which accompanied him for the rest of his life.

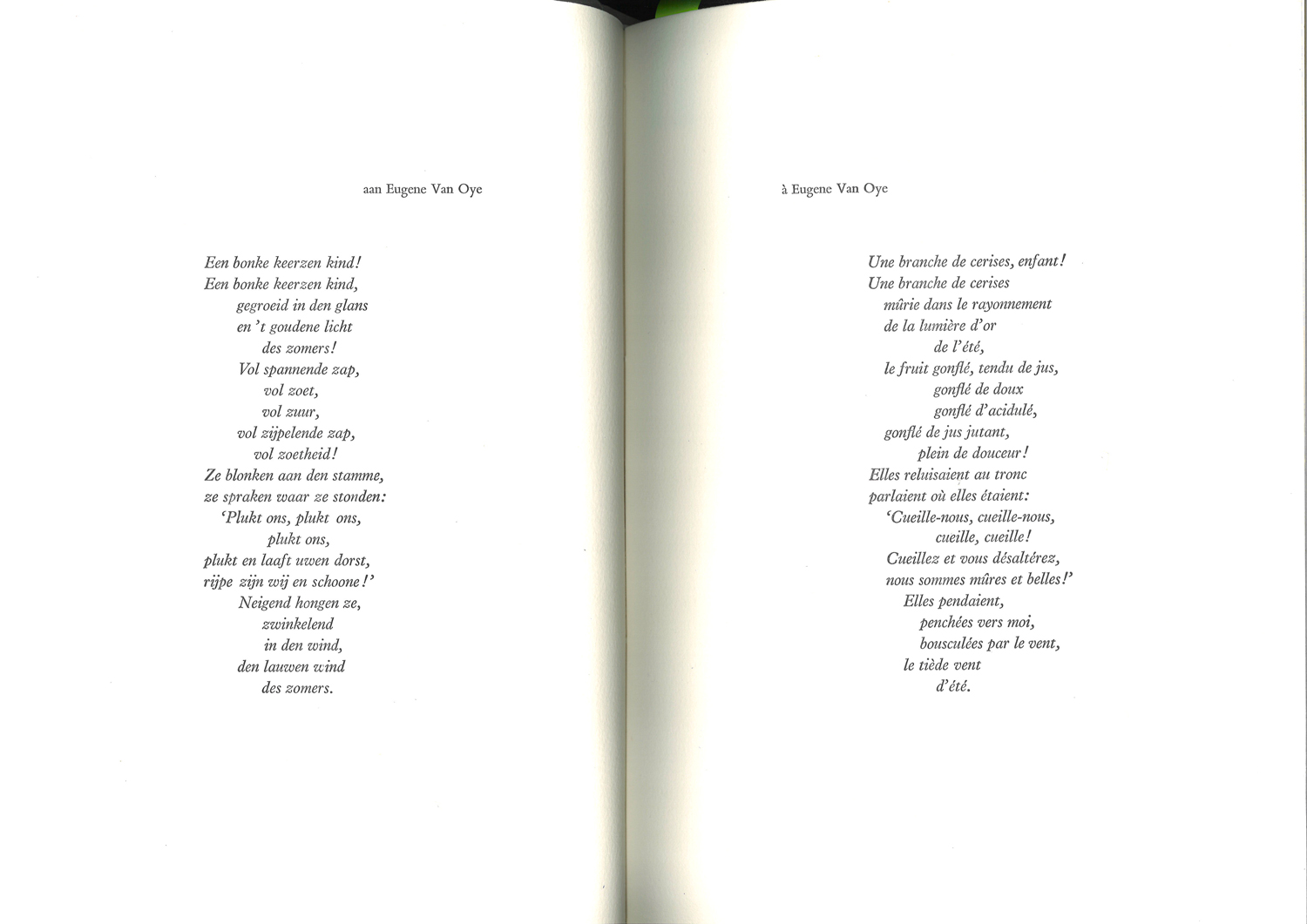

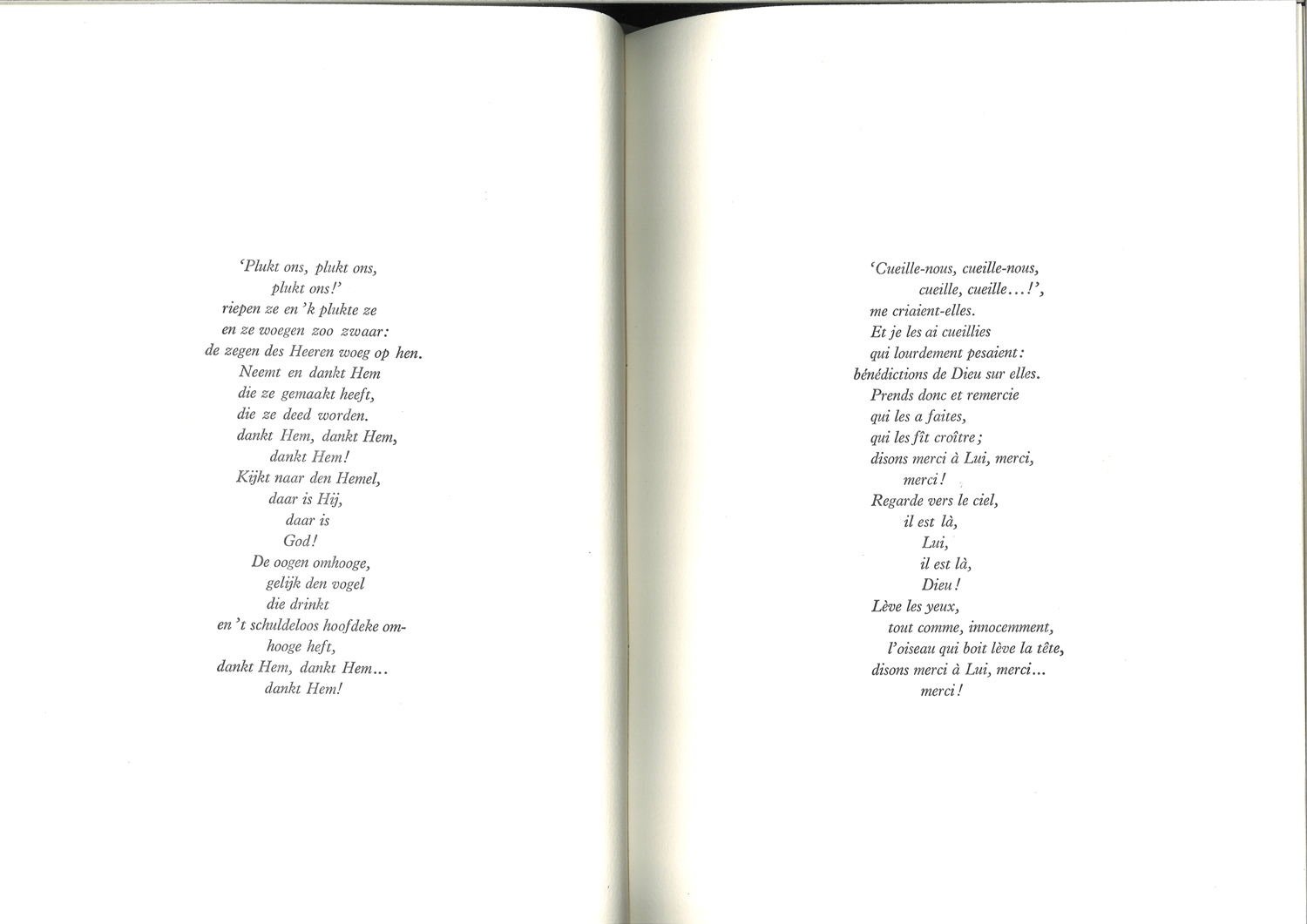

↑

A branch of cherry, child

Excerpt from Seuphor's French translation of Gezelle’s poem first published in his journal La Nouvelle Campagne and republished in Le Tombeau de Gezelle, Seuphor vertaalt Gezelle. Anthology of Seuphor's translations of the Flemish poet, edited by Agnes Caers, De Blauwe Reiger, in 19991910

the college

In 1910, Fernand entered the Jesuit College of Antwerp to pursue Greco-Latin studies in French. He would keep only painful memories from these years. Very early on, he came up against the rigidity of the fathers, and later endured their hostility when he committed to the Flemish movement. In a clandestine leaflet against them in 1917, he used, for the first time, the pseudonym Seuphor, an anagram of Orpheus taken from the title of a book by Salomon Reinach that he had in front of him.

“It was not thought out, simply because these letters were there, in large characters, white on mauve (…) But the name imposed itself little by little and, finally, remained. That day I had entered, with a light step, into another soul. (Le jeu de je, 1976).

It is also at the college that he felt his first deep poetic emotion when he disovered the works of the Flemish poet Guido Gezelle, introduced by his young professor of Flemish, the father De Clipelle.

“Gezelle never left me. He has been the companion, both peaceful and exhilarating, of my long life.” (Le jeu de je, 1976).

In the end, he decided to terminate his studies at the college in 1918. Taking this freedom gave him paradoxically the taste and the absolute necessity of studying, which accompanied him for the rest of his life.

↑

A branch of cherry, child

Excerpt from Seuphor's French translation of Gezelle’s poem first published in his journal La Nouvelle Campagne and republished in Le Tombeau de Gezelle, Seuphor vertaalt Gezelle. Anthology of Seuphor's translations of the Flemish poet, edited by Agnes Caers, De Blauwe Reiger, in 1999

•

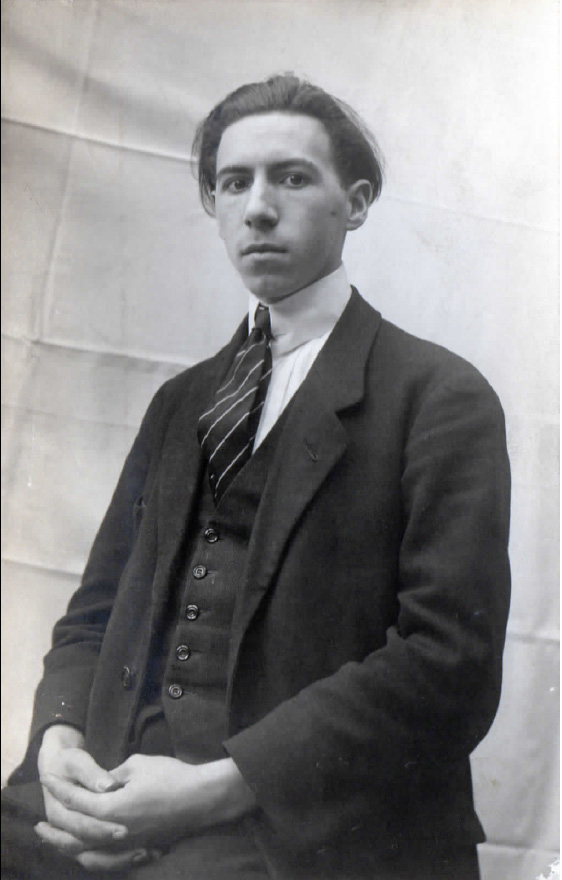

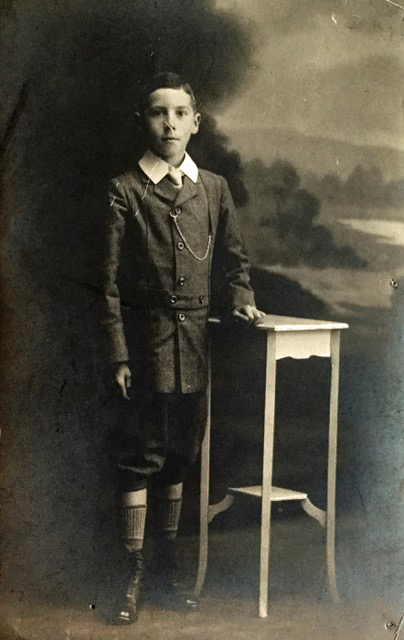

Seuphor

The young Fernand in school clothes around 1912

↑

Guido Gezelle

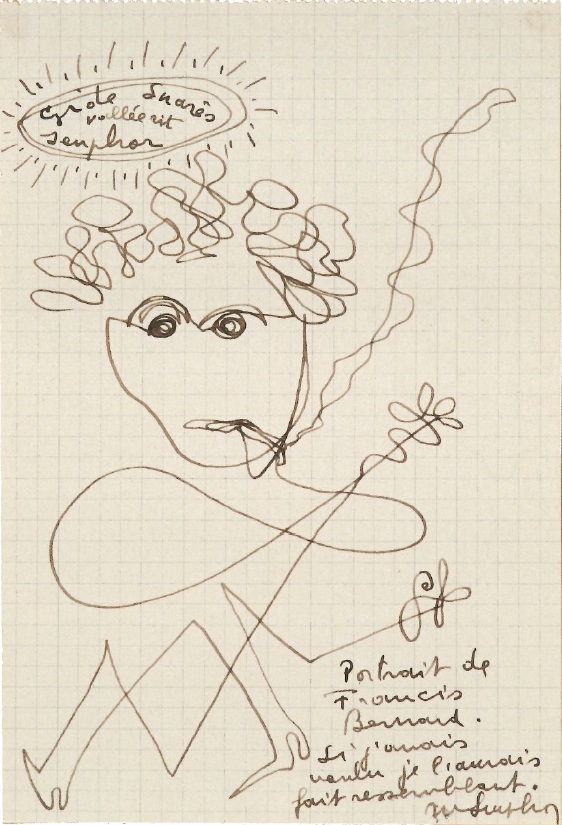

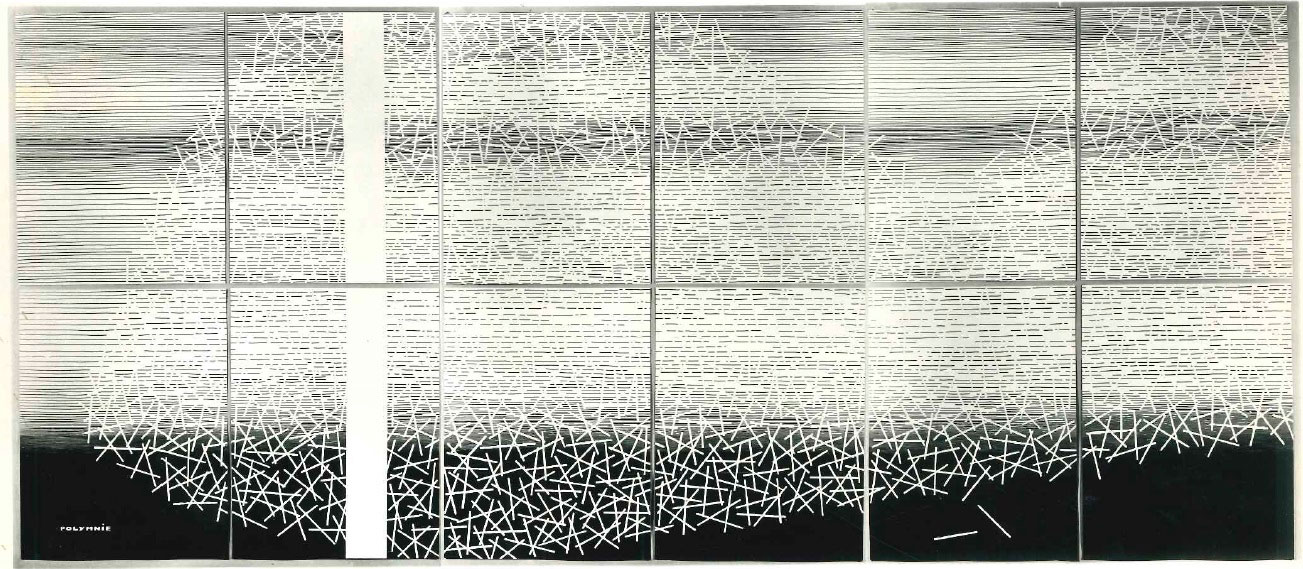

Lacuna drawing by Seuphor, April 5, 19641919

engagement

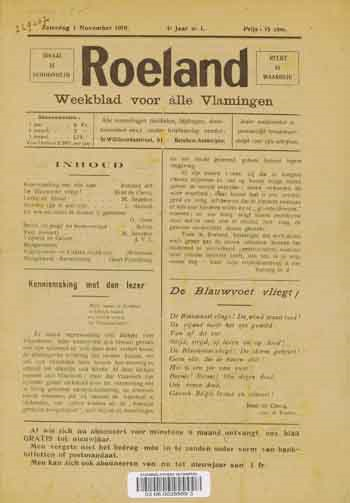

Following the armistice, in 1919 Seuphor became actively involved in the Flemish movement. During the occupation, he had refrained from publicly showing his convictions because he refused to be associated with the activists who had not hesitated to take advantage of the protection of the German army to make their demands. He founded two small militant magazines, De Klauwaert – (the man with the claw) and – Roeland, and participated in the Flemish demonstrations. The police repression of July 11, 1920, during the commemorative demonstration of the Battle of the Golden Spurs, left a deep impression on him. On the Antwerp Grote Markt, the mounted police charged the demonstrators, and his friend Herman van den Reeck was killed before his eyes by a policeman, while he himself received two saber blows on the head.

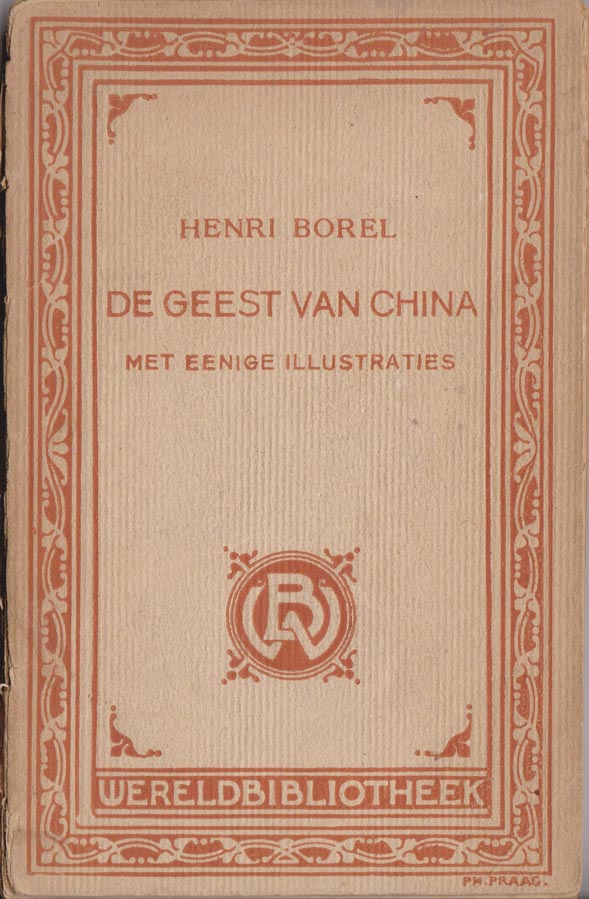

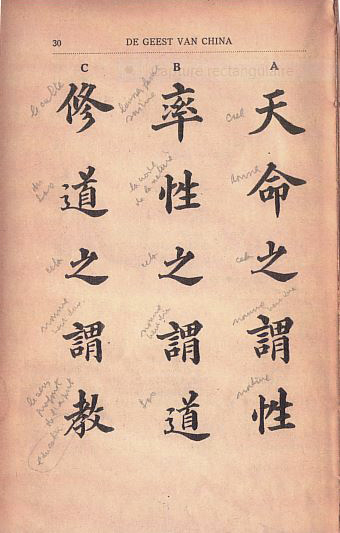

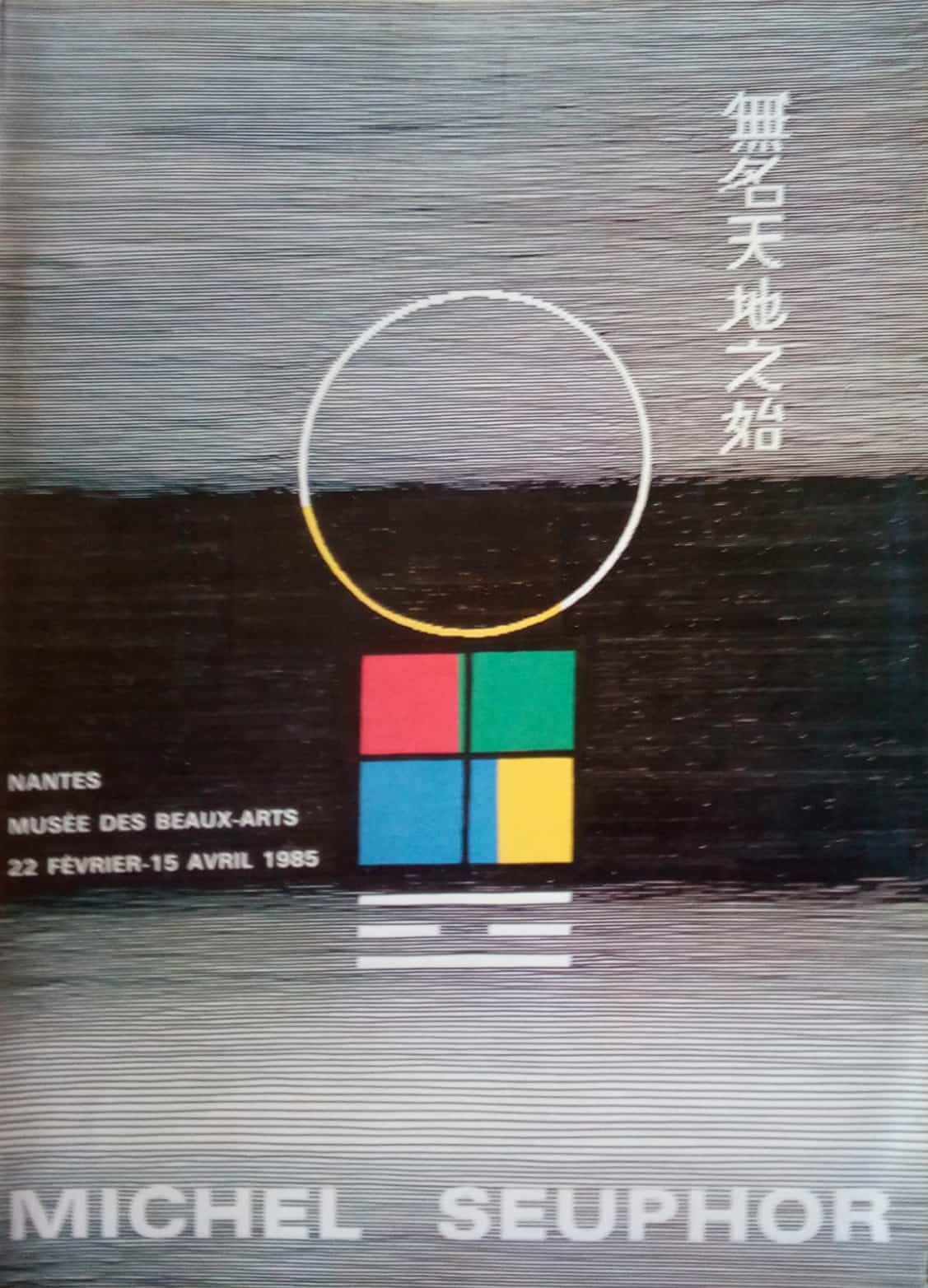

Seuphor’s interest soon extended beyond Flanders. While trying out various professional careers, without much enthusiasm, he read avidly and shared with his friends his discoveries of authors such as Walt Whitman, Nietzsche, Multatuli, Pascal, Romain Rolland, etc. He also discovered oriental philosophies, notably through De Geest van China – L’esprit de la Chine (The Spirit of China) by Henri Borel, found in the pocket collection published by the Wereldbibliotheek of Amsterdam. It was a shock, a salutary and memorable opening of mind.

“Greco-Latin studies were about the West only and, suddenly, I understood that the world has two parts and that it is round” (Un siècle de liberté, page 19). These various readings instilled in him what he would later call “the definitive foundations of his moral being”, setting him on a quest for the universal his entire life.

•

Seuphor and his Antwerp friends, from left to right: Top row: Marc Edo Tralbaut, Michel Seuphor, Jan de Roover, Lode Krinkels; Middle row: Leo Steinen, Alice Nahon, Mevr. Stuyts-Lambeaux, Herman Engels, Sylvia de Ridder; Bottom row: Geert Pijnenburg, Flora de Lannoy, Magda Stuyts. Copyright: Archive of Geert Pijnenburg, Letterenhuis Antwerp, 1921

1919

engagement

Following the armistice, in 1919 Seuphor became actively involved in the Flemish movement. During the occupation, he had refrained from publicly showing his convictions because he refused to be associated with the activists who had not hesitated to take advantage of the protection of the German army to make their demands. He founded two small militant magazines, De Klauwaert – (the man with the claw) and – Roeland, and participated in the Flemish demonstrations. The police repression of July 11, 1920, during the commemorative demonstration of the Battle of the Golden Spurs, left a deep impression on him. On the Antwerp Grote Markt, the mounted police charged the demonstrators, and his friend Herman van den Reeck was killed before his eyes by a policeman, while he himself received two saber blows on the head.

Seuphor’s interest soon extended beyond Flanders. While trying out various professional careers, without much enthusiasm, he read avidly and shared with his friends his discoveries of authors such as Walt Whitman, Nietzsche, Multatuli, Pascal, Romain Rolland, etc. He also discovered oriental philosophies, notably through De Geest van China – L’esprit de la Chine (The Spirit of China) by Henri Borel, found in the pocket collection published by the Wereldbibliotheek of Amsterdam. It was a shock, a salutary and memorable opening of mind.

“Greco-Latin studies were about the West only and, suddenly, I understood that the world has two parts and that it is round” (Un siècle de liberté, page 19). These various readings instilled in him what he would later call “the definitive foundations of his moral being”, setting him on a quest for the universal his entire life.

•

Seuphor and his Antwerp friends, from left to right: Top row: Marc Edo Tralbaut, Michel Seuphor, Jan de Roover, Lode Krinkels; Middle row: Leo Steinen, Alice Nahon, Mevr. Stuyts-Lambeaux, Herman Engels, Sylvia de Ridder; Bottom row: Geert Pijnenburg, Flora de Lannoy, Magda Stuyts. Copyright: Archive of Geert Pijnenburg, Letterenhuis Antwerp, 1921

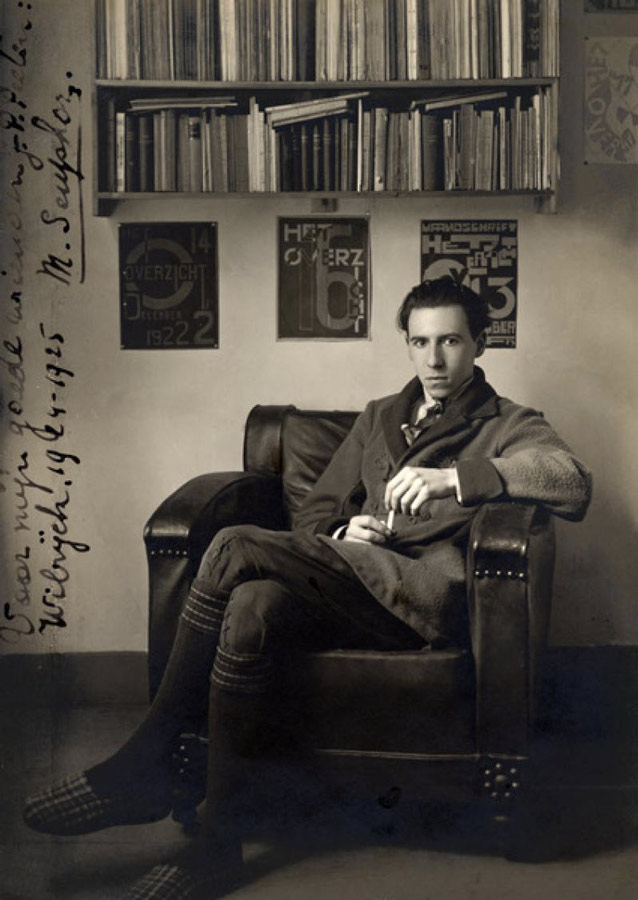

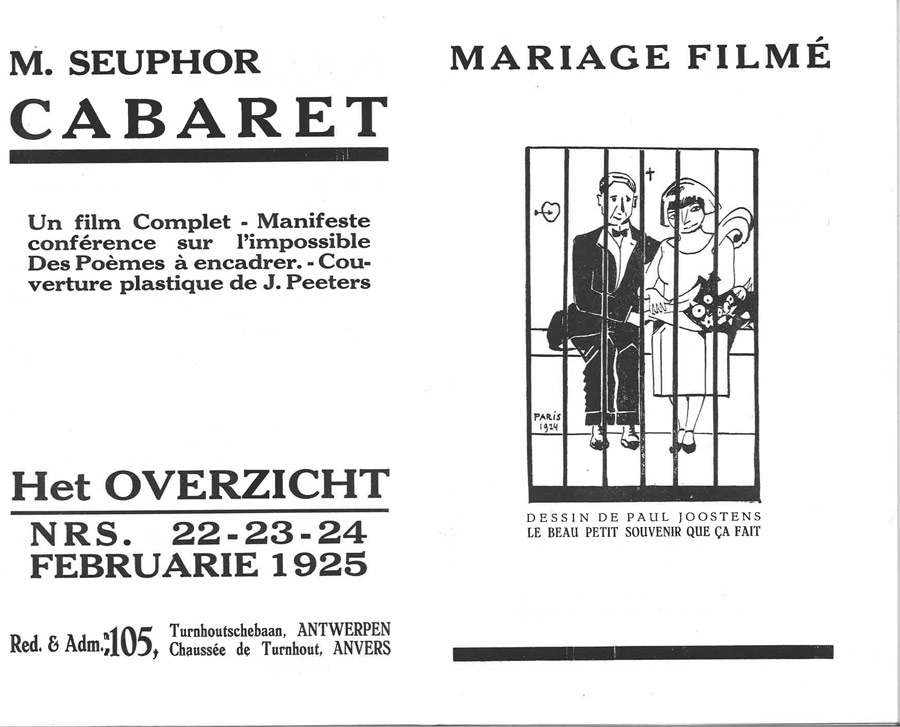

1921 – 1925

Plunge into abstract art

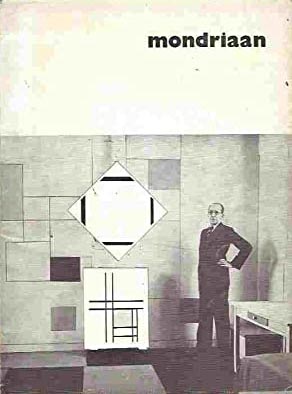

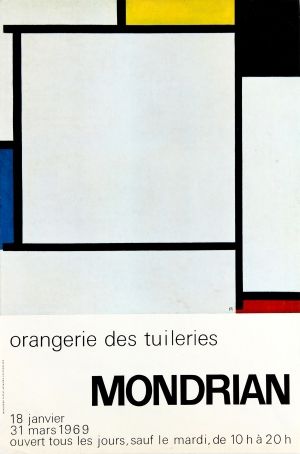

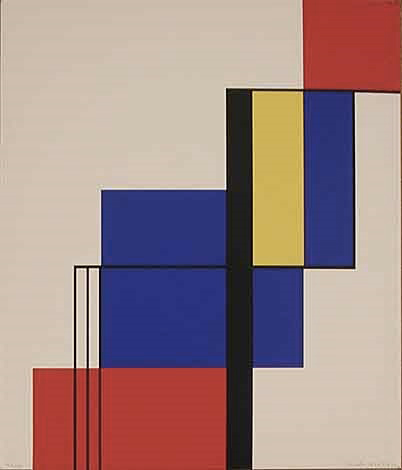

Seuphor published poems in several periodicals (Herleving, De Smeden, De Shelde) and graduated as a librarian. He decided to sell all his books to start a new magazine : Het Overzicht, dedicated to ‘the arts, letters, and humanity’, in collaboration with his friend Geert Pijnenburg. The first issue appeared on 15 June 1921 and was followed by 24 others until March 1925. Initially Flamingant and literary, the magazine quickly became international and avant-garde. From 1922 onwards, it became involved in the promotion of abstract art. This transformation followed Seuphor’s discovery of Piet Mondrian’s neoplasticism during a conference given by Theo van Doesburg, co-founder of the De Stijl movement and its magazine, at the Athenaeum in Antwerp on December 2, 1921. Moved by the discovery of Mondrian’s ideas, Seuphor decided that same evening to change the editorial line of his magazine and to share the direction with the painter Joseph Peeters. For him, the magazine had imperatively to open up to this new conception of the arts, which was also a new conception of humanity.

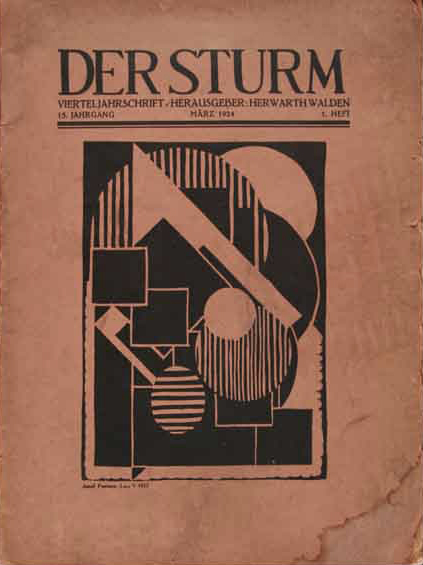

In December 1922, Seuphor made his first important trip abroad to Berlin, accompanying Joseph Peeters and his wife. There he met, among others, the poet Filippo Marinetti (the founder of Italian Futurism) and his colleague the abstract painter Enrico Prampolini; the Hungarian painter László Moholy-Nagy (soon to be appointed professor at the Bauhaus), the Russian sculptor Naum Gabo, the sculptor Rudolf Belling ; as well as Herwarth Walden, who was the director of the German magazine Der Sturm at the center of modern art in Berlin (Seuphor later contributed poems to it), the architect Walter Gropius, the committed critic Adolf Behne, and Paul Westheim, the director of Das Kunstblatt, a cosmopolitan magazine dedicated to living artists that was eventually interrupted when Westheim fled Nazism in 1933.

In April 1923, in order to meet Piet Mondrian, Seuphor made his first trip to Paris, which was followed by several others in the following years. Of his first visit to Mondrian’s studio, he wrote: “When I left, I had the feeling of having encountered, for the first time in my life, the perfect human balance. The lofty idea I had of the man and my admiration for his work gave way to something different, an attraction, an intimate feeling, what is generally called friendship” (Le jeu de je, 1976).

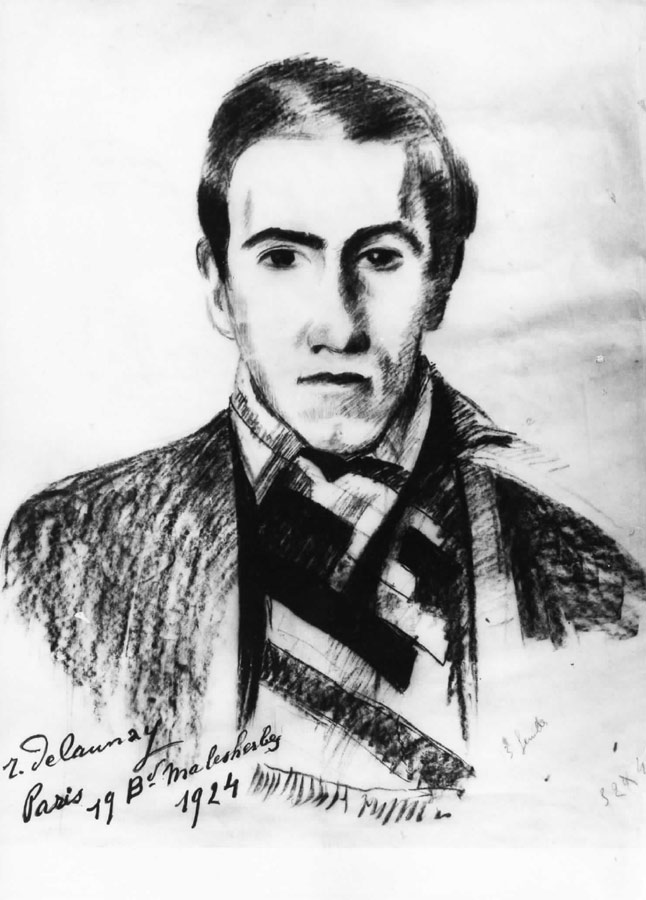

During this first stay, he also became acquainted with the France-based avant-garde. He met the artist couple Robert and Sonia Delaunay, as well as many other artists such as Fernand Léger, Amédée Ozenfant, Albert Gleizes, Mikhail Larionov, Constantin Brancusi, Jacques Lipchitz, Louis Marcoussis, Picasso, Paul Dermée, Yvan Goll, Céline Arnauld, Tristan Tzara, Joseph Delteil, René Crevel, Jean Cocteau and Blaise Cendrars.

In November, he also travelled to Holland and befriended the Dutch architects Hendrik Petrus Berlage and Jacobus Oud, who became collaborators of Het Overzicht.

He also visited the Kröller collection, which later became the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, and stayed in Amsterdam with the painter and poet Albert Carel Willink. Het Overzicht reflects these international connections. The names of the entire European avant-garde can be seen in it, with articles, poems, and reproductions of works by Delaunay, Prampolini, Marinetti, Tzara, Kandinsky, Dermée, Goll, Picasso, Malespine, Huidobro, Prokofieff, Manuel de Falla, Russolo, Belling, Walden, Larionov, Gontcharova, Gleizes, Fernand Léger, Ernst Kállai, Kurt Schwitters, Péri, Soupault, Juan Gris, Picasso, Kassak, Moholy-Nagy, Dexel, Oud, Berlage, Huszar, Guillermo De Torre, Cangiullo, Behrens Hangeler, Servranckx, Mesens, Joseph Peeters, Maes, De Boeck, Van Ostaijen, Victor Bourgeois, Maurice Casteels, Louis van der Swaelmen, Gaston Burssens, Paul Joostens, etc. These international relations nourished Seuphor’s aspirations to universalism, definitively distancing him from flamingantisme.

At the end of 1923 and beginning of 1924, several poems by Seuphor appeared in Der Sturm, in Dutch and in German translation. He traveled a lot in France, to Menton in the south, even going to Tunis, and several times to Paris. He attended the wedding of Paul Joostens with Mado, which inspired him to write Mariage filmé, a work that belongs to the Dadaist movement.

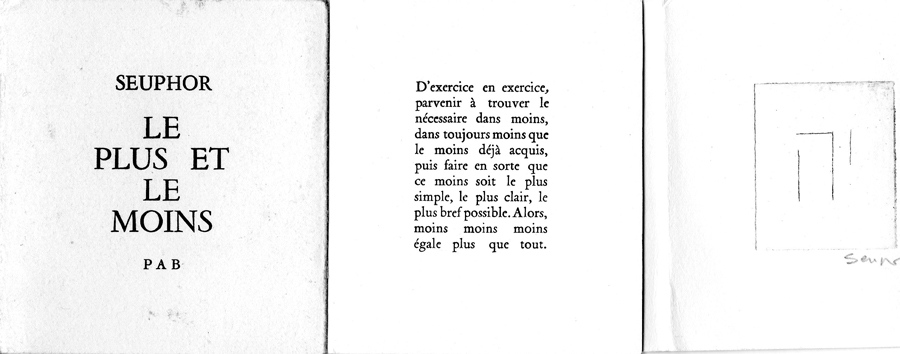

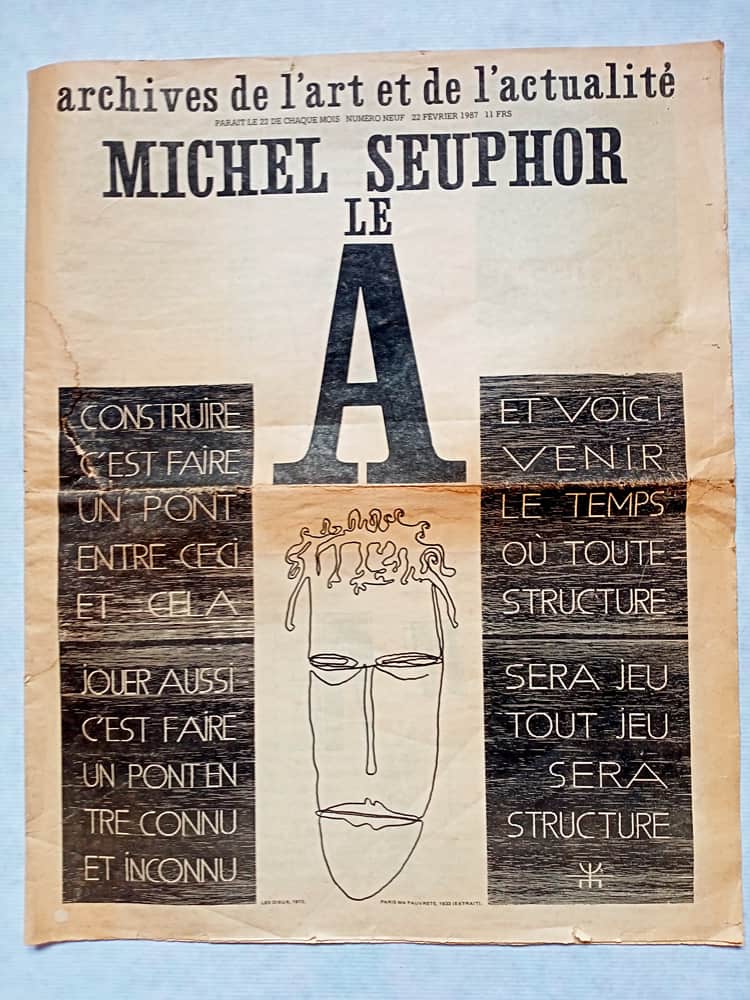

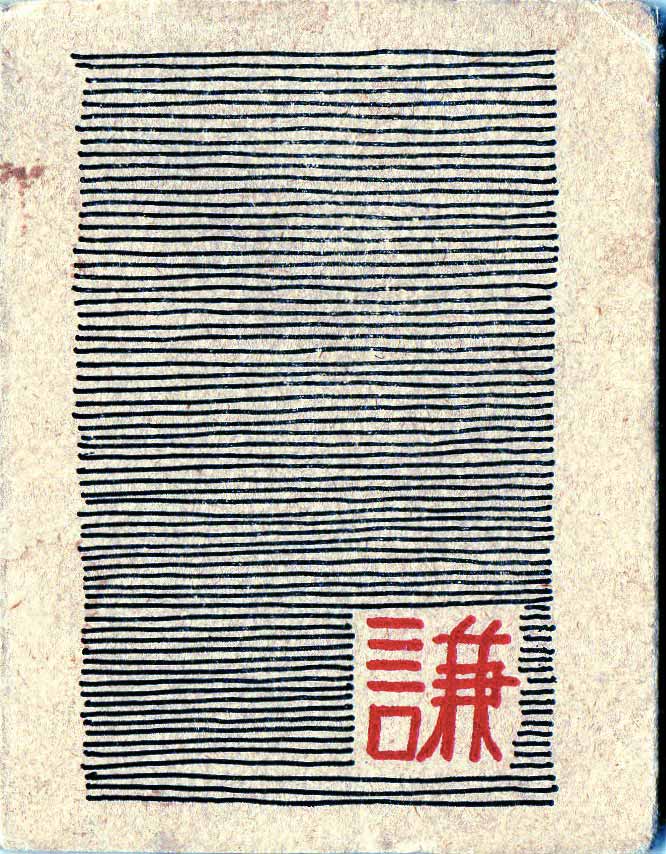

Seuphor also published his literary works in Het Overzicht, where he also experimented with typography. He invited Kurt Schwitters, whose poetry he had discovered and admired, to collaborate in Het Overzicht. His own poetry evolved; it began to give more importance to words, to the rhythm of the sentence and to musicality. His most representative writings of that time also show the growing importance of France: for example, Te Parijs in trombe, a text in Dutch with a drawing by Delaunay, and Seuphor en or, which was edited with a cover by Schwitters.

Meanwhile, in Antwerp, difficulties arose in his collaboration with Peeters, who was turning his attention to Paul van Ostaijen and Eddy du Perron. After the publication of the numbers 22-23-24 of Het Overzicht under the title Cabaret in March 1925, the discord with Peeters increased to the point that Seuphor decided to end their collaboration and to move to Paris.

1921 – 1925

Plunge into abstract art

Seuphor published poems in several periodicals (Herleving, De Smeden, De Shelde) and graduated as a librarian. He decided to sell all his books to start a new magazine : Het Overzicht, dedicated to ‘the arts, letters, and humanity’, in collaboration with his friend Geert Pijnenburg. The first issue appeared on 15 June 1921 and was followed by 24 others until March 1925. Initially Flamingant and literary, the magazine quickly became international and avant-garde. From 1922 onwards, it became involved in the promotion of abstract art. This transformation followed Seuphor’s discovery of Piet Mondrian’s neoplasticism during a conference given by Theo van Doesburg, co-founder of the De Stijl movement and its magazine, at the Athenaeum in Antwerp on December 2, 1921. Moved by the discovery of Mondrian’s ideas, Seuphor decided that same evening to change the editorial line of his magazine and to share the direction with the painter Joseph Peeters. For him, the magazine had imperatively to open up to this new conception of the arts, which was also a new conception of humanity.

In December 1922, Seuphor made his first important trip abroad to Berlin, accompanying Joseph Peeters and his wife. There he met, among others, the poet Filippo Marinetti (the founder of Italian Futurism) and his colleague the abstract painter Enrico Prampolini; the Hungarian painter László Moholy-Nagy (soon to be appointed professor at the Bauhaus), the Russian sculptor Naum Gabo, the sculptor Rudolf Belling ; as well as Herwarth Walden, who was the director of the German magazine Der Sturm at the center of modern art in Berlin (Seuphor later contributed poems to it), the architect Walter Gropius, the committed critic Adolf Behne, and Paul Westheim, the director of Das Kunstblatt, a cosmopolitan magazine dedicated to living artists that was eventually interrupted when Westheim fled Nazism in 1933.

In April 1923, in order to meet Piet Mondrian, Seuphor made his first trip to Paris, which was followed by several others in the following years. Of his first visit to Mondrian’s studio, he wrote: “When I left, I had the feeling of having encountered, for the first time in my life, the perfect human balance. The lofty idea I had of the man and my admiration for his work gave way to something different, an attraction, an intimate feeling, what is generally called friendship” (Le jeu de je, 1976).

During this first stay, he also became acquainted with the France-based avant-garde. He met the artist couple Robert and Sonia Delaunay, as well as many other artists such as Fernand Léger, Amédée Ozenfant, Albert Gleizes, Mikhail Larionov, Constantin Brancusi, Jacques Lipchitz, Louis Marcoussis, Picasso, Paul Dermée, Yvan Goll, Céline Arnauld, Tristan Tzara, Joseph Delteil, René Crevel, Jean Cocteau and Blaise Cendrars.

In November, he also travelled to Holland and befriended the Dutch architects Hendrik Petrus Berlage and Jacobus Oud, who became collaborators of Het Overzicht.

He also visited the Kröller collection, which later became the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, and stayed in Amsterdam with the painter and poet Albert Carel Willink. Het Overzicht reflects these international connections. The names of the entire European avant-garde can be seen in it, with articles, poems, and reproductions of works by Delaunay, Prampolini, Marinetti, Tzara, Kandinsky, Dermée, Goll, Picasso, Malespine, Huidobro, Prokofieff, Manuel de Falla, Russolo, Belling, Walden, Larionov, Gontcharova, Gleizes, Fernand Léger, Ernst Kállai, Kurt Schwitters, Péri, Soupault, Juan Gris, Picasso, Kassak, Moholy-Nagy, Dexel, Oud, Berlage, Huszar, Guillermo De Torre, Cangiullo, Behrens Hangeler, Servranckx, Mesens, Joseph Peeters, Maes, De Boeck, Van Ostaijen, Victor Bourgeois, Maurice Casteels, Louis van der Swaelmen, Gaston Burssens, Paul Joostens, etc. These international relations nourished Seuphor’s aspirations to universalism, definitively distancing him from flamingantisme.

At the end of 1923 and beginning of 1924, several poems by Seuphor appeared in Der Sturm, in Dutch and in German translation. He traveled a lot in France, to Menton in the south, even going to Tunis, and several times to Paris. He attended the wedding of Paul Joostens with Mado, which inspired him to write Mariage filmé, a work that belongs to the Dadaist movement.

Seuphor also published his literary works in Het Overzicht, where he also experimented with typography. He invited Kurt Schwitters, whose poetry he had discovered and admired, to collaborate in Het Overzicht. His own poetry evolved; it began to give more importance to words, to the rhythm of the sentence and to musicality. His most representative writings of that time also show the growing importance of France: for example, Te Parijs in trombe, a text in Dutch with a drawing by Delaunay, and Seuphor en or, which was edited with a cover by Schwitters.

Meanwhile, in Antwerp, difficulties arose in his collaboration with Peeters, who was turning his attention to Paul van Ostaijen and Eddy du Perron. After the publication of the numbers 22-23-24 of Het Overzicht under the title Cabaret in March 1925, the discord with Peeters increased to the point that Seuphor decided to end their collaboration and to move to Paris.

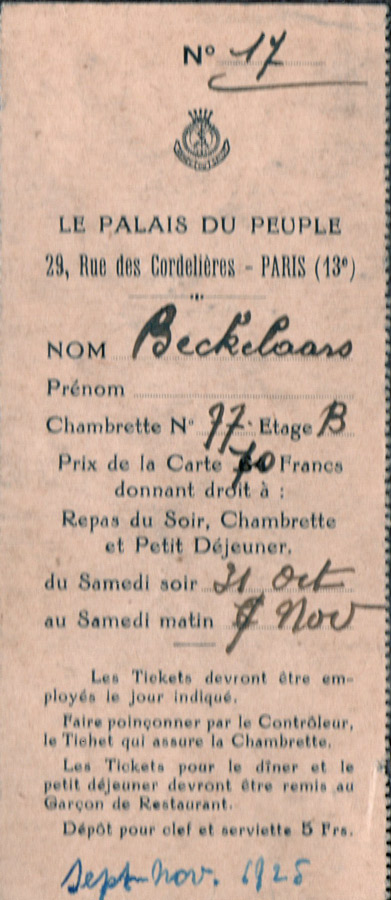

1925 – 1928

the European avant-garde

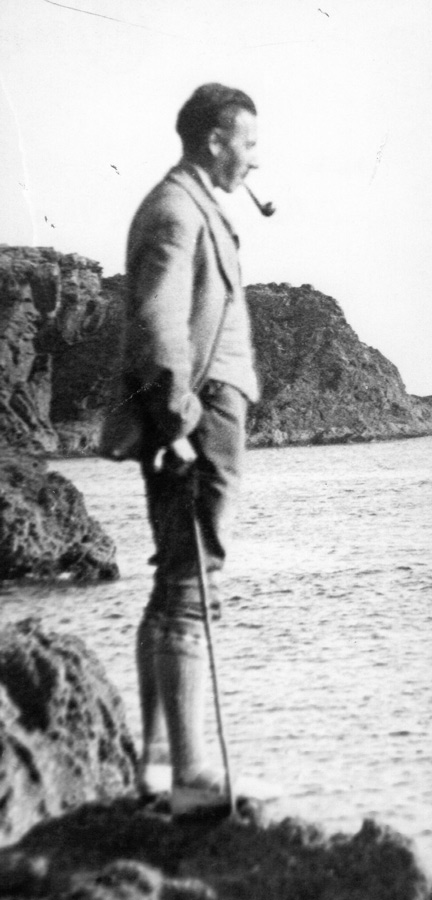

Upon his arrival in Paris, Seuphor survived poorly and stayed at various addresses, notably the Hotel Monaco, rue Champollion, or at the home of the Czech painter Zravy, avenue de Clichy, but also, for a while, at the Salvation Army. In order to overcome a bad cold, on the advice of Theo Van Doesburg (with whom, along with Paul Dermée and Céline Arnauld, there were talks of creating a new magazine entitled Code, which never saw the light), he spent the summer of 1925 at the Hostellerie des Cormorans in Kervilahouen at Belle-île-en-mer, run by Mr. Ratel, a friend and protector of artists. This stay allowed him to write his first poems of verbal music, which were published in 1926 in a collection entitled Diaphragme intérieur et un drapeau. At the end of the year, he left for Menton, where he met George Vantongerloo and learned Italian to prepare for a trip to Naples.

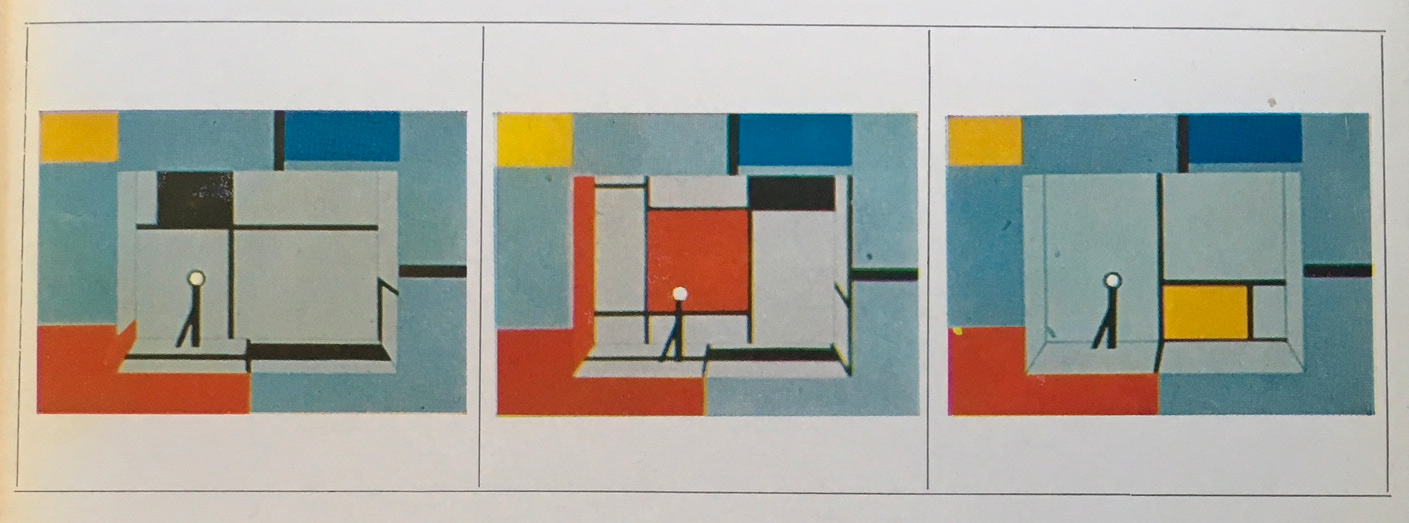

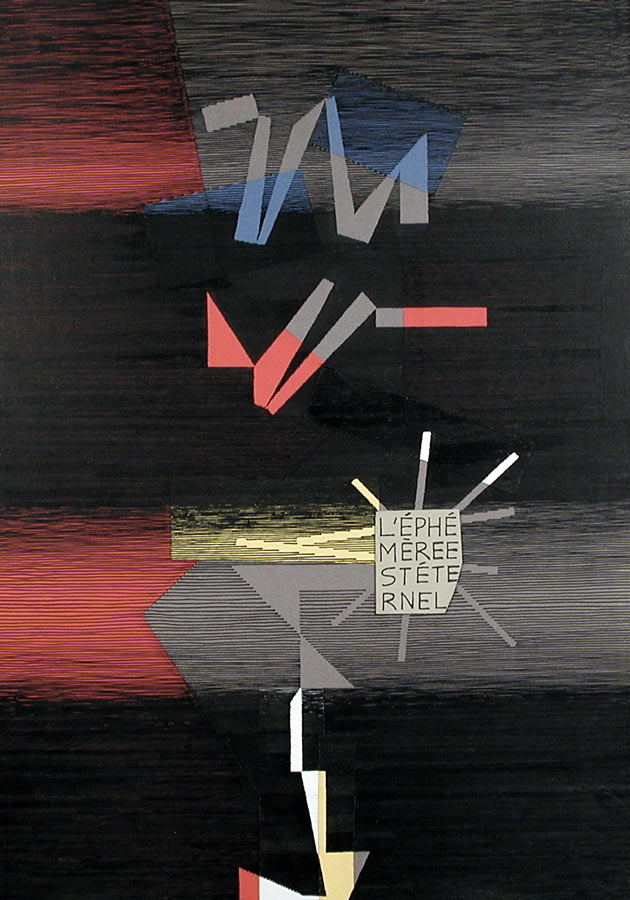

In early 1926, Seuphor went to Italy. He visited Paestum, Naples, Rome, and Venice. He joined some of the Futurists he had met in Berlin and strengthened his relationship with certain members of the group, including Cangiullo, Marinetti, Prampolini and Balla. Seuphor hoped to interest Marinetti in joining a project for a ‘world congress of modern art’, but he failed. However, his stay in Rome inspired him, stimulated by Balla, to write L’éphémère est éternel,

a play of ‘theatre-antitheater’, for which Mondrian composed a model of the sets when Seuphor gave him the text to read upon his return to Paris. Unfortunately, the first performance of the play, scheduled in Lyon, was cancelled at the last minute. It was not until 1968 that it was staged for the first time in Milan in Italian, by the experimental group Il Parametro, and then another decade before it was staged in its original French version, in Paris, at the George Pompidou Center, in 1977.

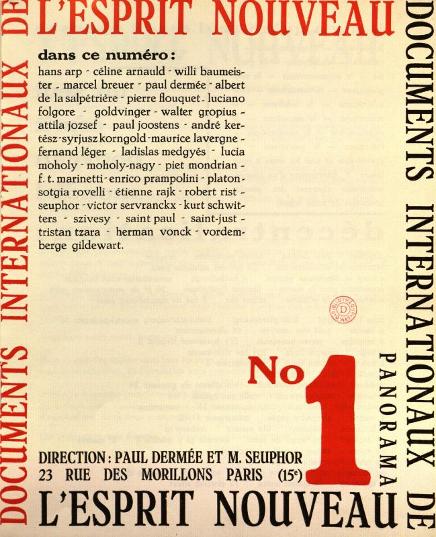

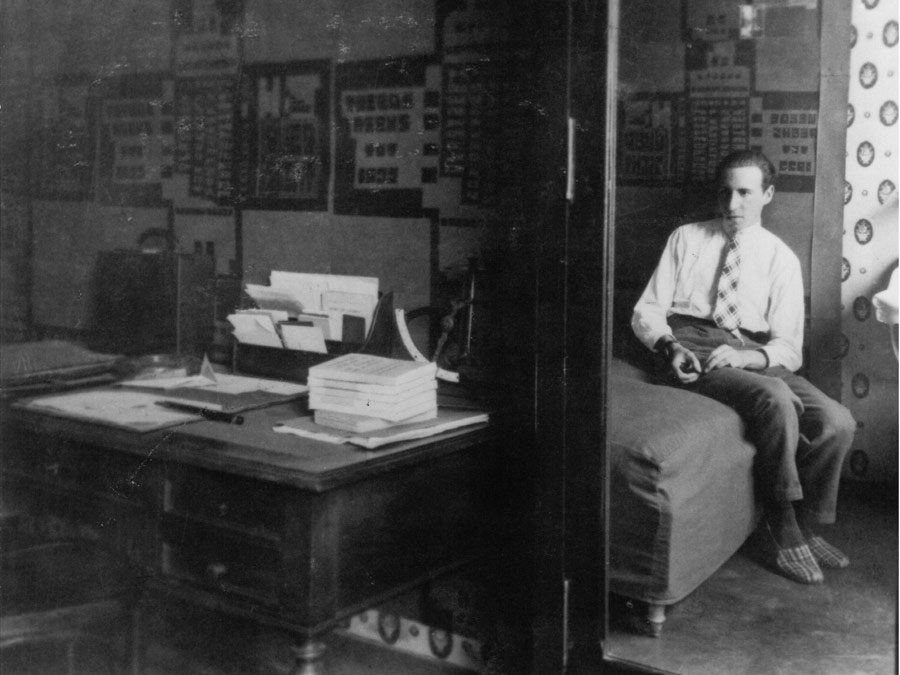

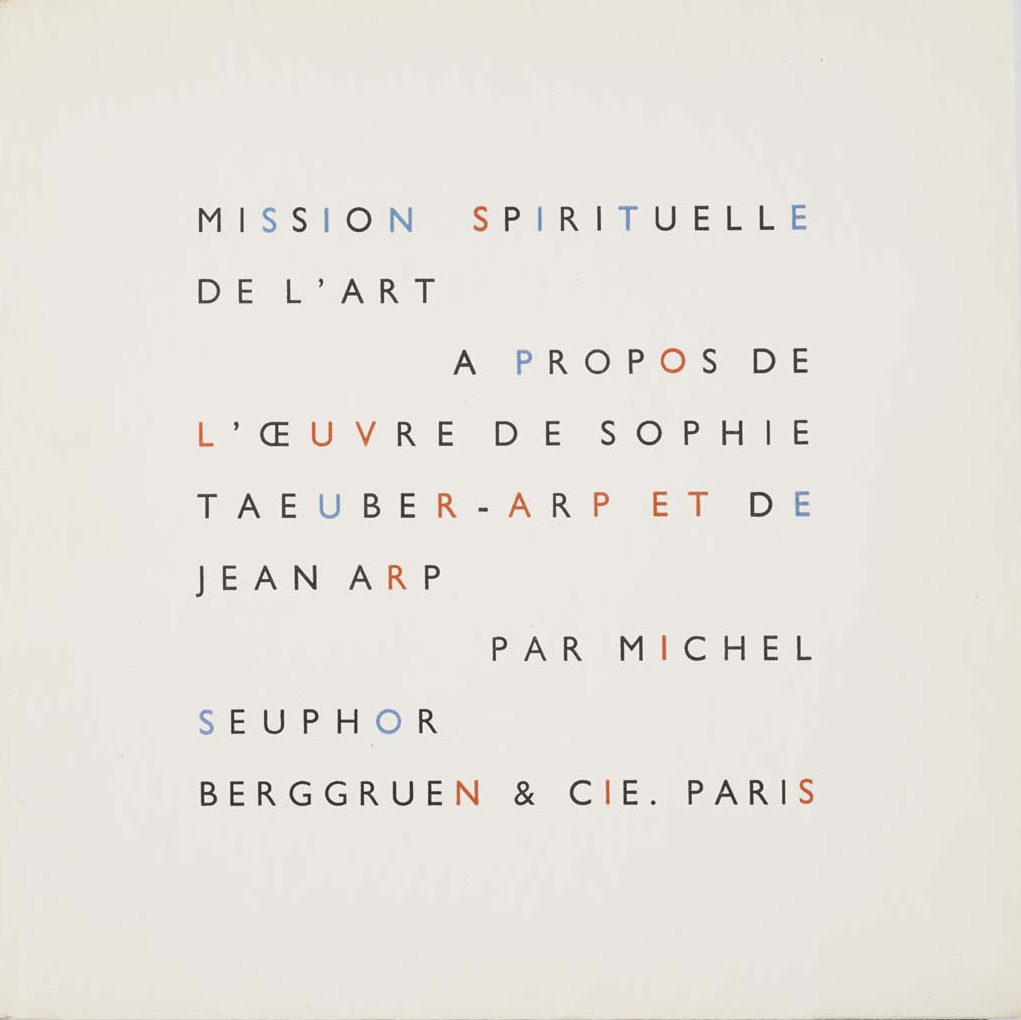

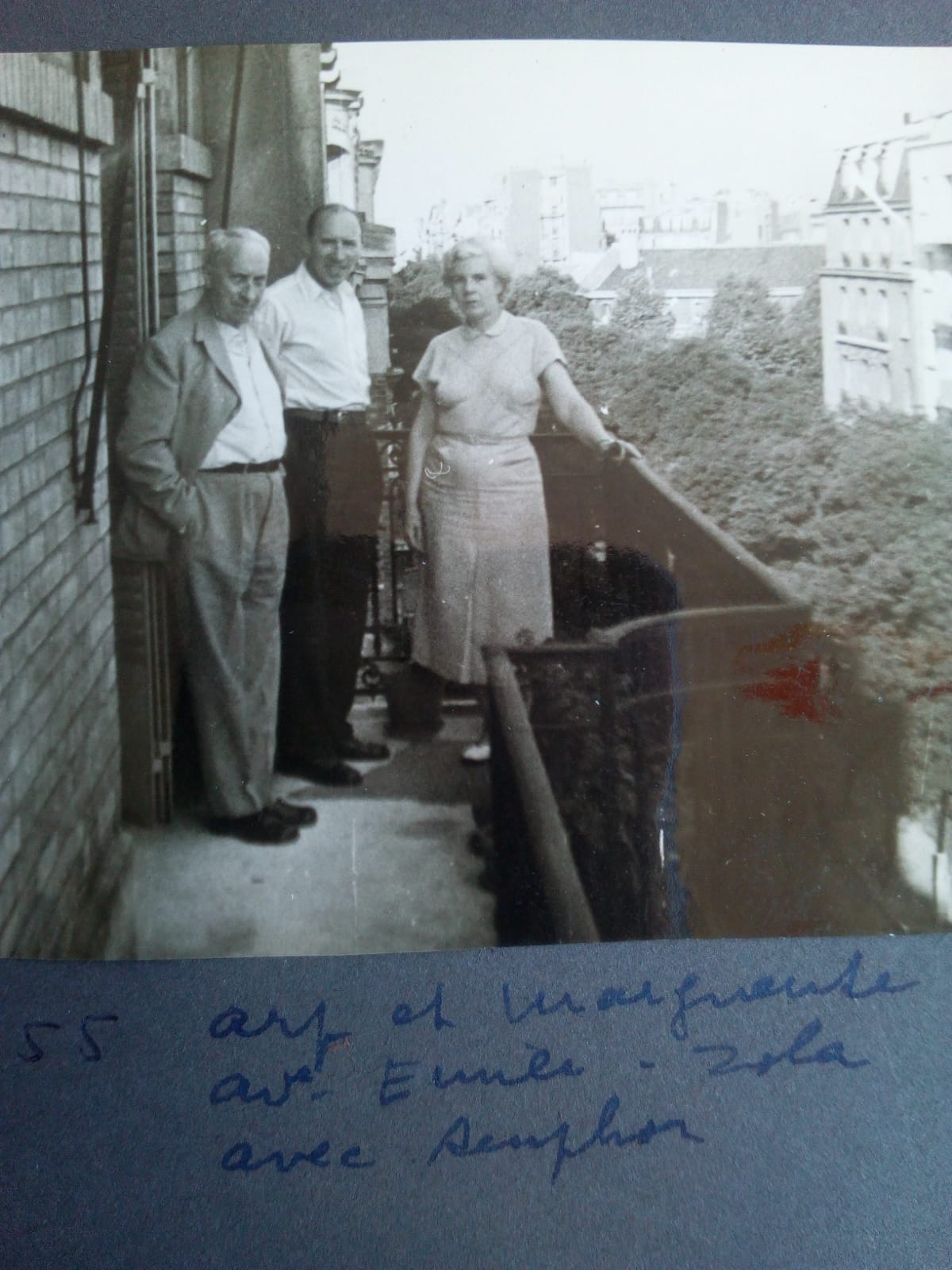

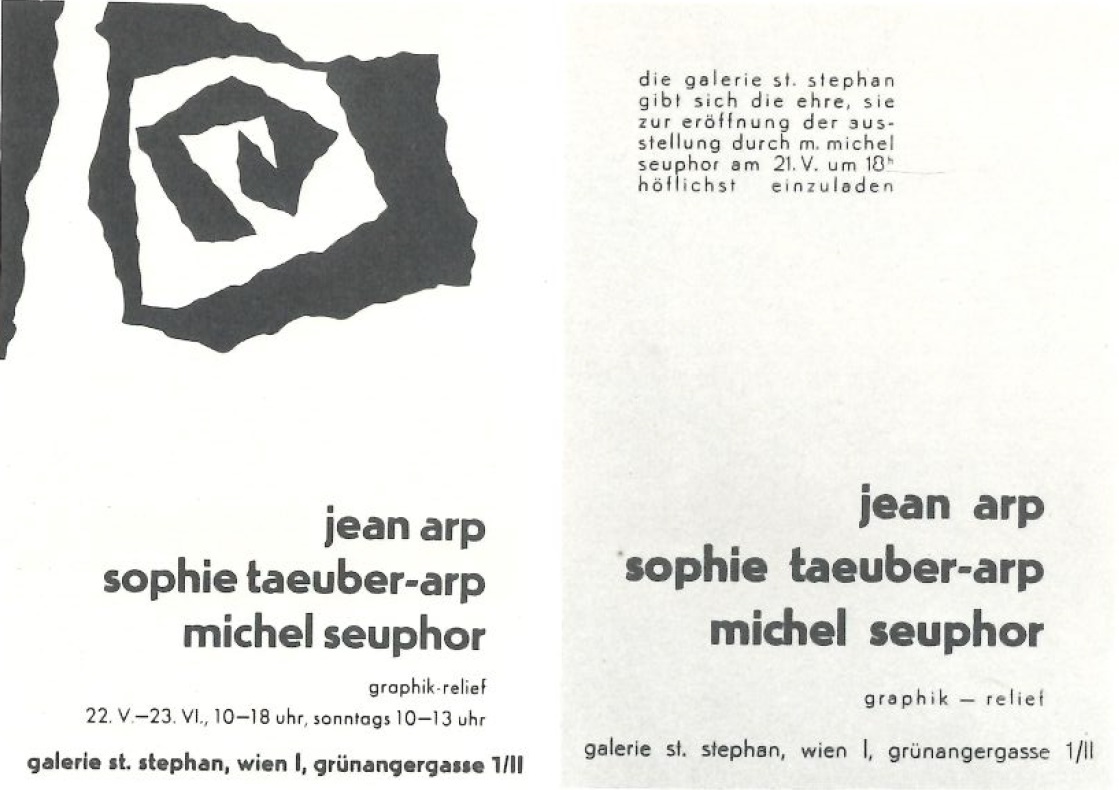

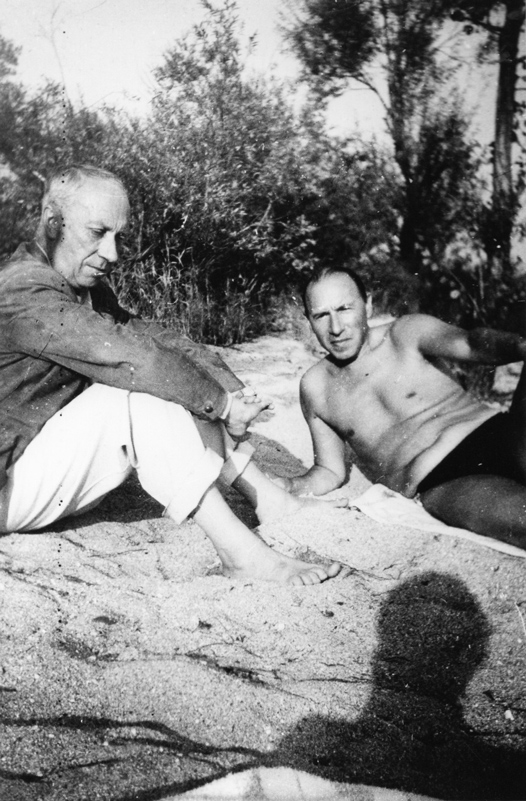

Back in Paris after a detour through Budapest, Seuphor barely survived thanks to a job as translator of foreign radio programs for Parisian newspapers, obtained through Paul Dermée. However, his ambition remained to create a new art magazine. In October, he had a major encounter with Hans Arp (who would sign Jean Arp after the advent of Nazism) and Sophie Taeuber who, along with Mondrian, would become his closest friends. They gave him a camera to help him earn a living by making portraits, but what interested him was the photographer’s eye, not the subject. Thus, he guided the young Hungarian photographer André Kertész through Paris and experimented with photography himself. At this time, he also began to paint néoplastic gouaches. However, his energy was still mainly dedicated to the preparation, with Paul Dermée and Enrico Prampolini, of a new magazine entitled Les documents internationaux de l’esprit nouveau.

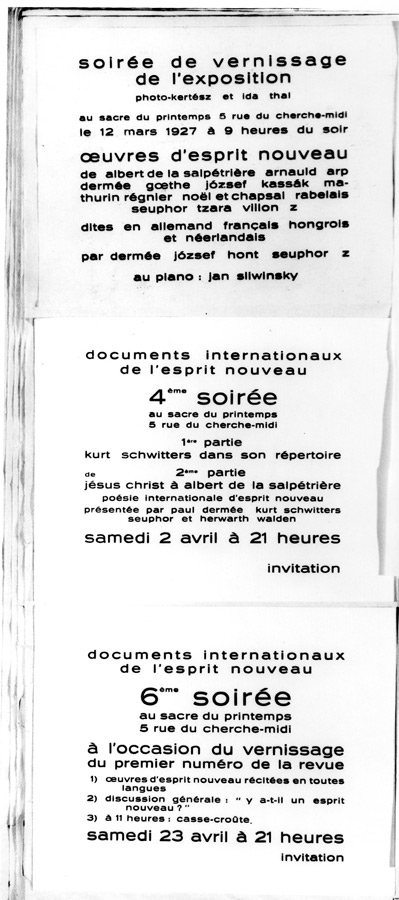

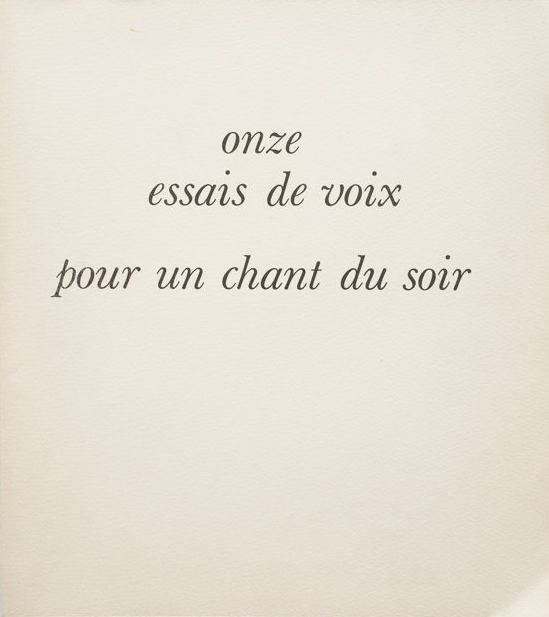

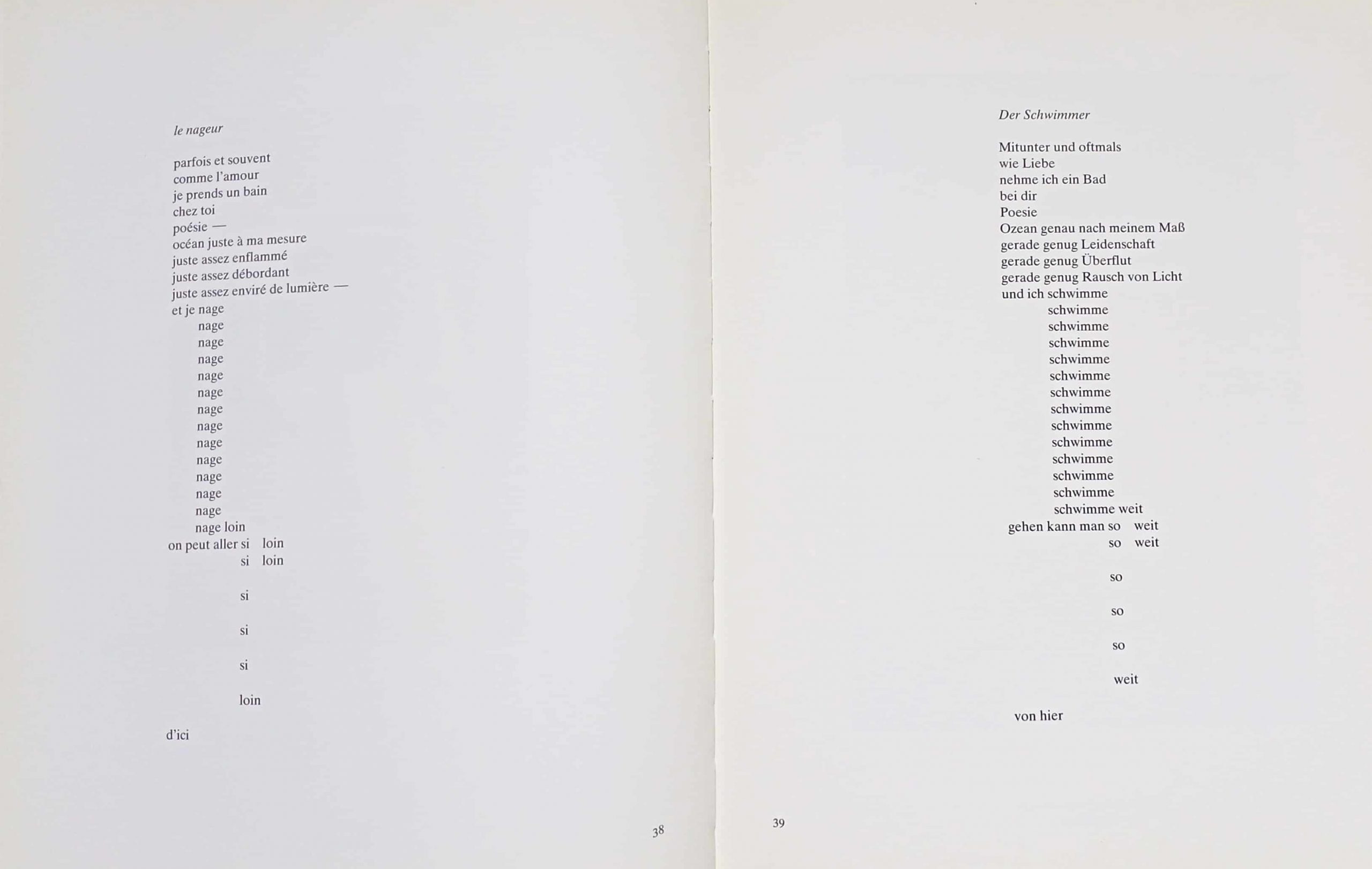

The first and only copy (for lack of financing for the following issues) of Les documents internationaux de l’esprit nouveau appeared in 1927. To promote this initiative, Seuphor and Dermée organized a series of eleven literary evenings at the Parisian gallery Le Sacre du Printemps, at 5 rue du Cherche-Midi. Very quickly popular, these evenings brought together artists of the European avant-garde such as Russolo, Pevsner, Mondrian, Léger, the Delaunays, Arp, Marinetti, Tzara, Cocteau, Cendrars, Delteil, Goll, Charchoune, Walden and others. There, Seuphor recited for the first time poems of verbal music such as « Tout en roulant les “R”», which is incorporated in Lecture élémentaire published in 1928. The Sacre du Printemps also hosted an exhibition in which Seuphor and Dermée brought together the works of the Hungarian Ida Thal, the Belgian Victor Delhez, the Dutch typographer and writer Hendrik Nicolaas Werkman, and photographs by André Kertesz. However, at the beginning of June 1927, the owner of the gallery notified them of his decision to put an end to these evenings, following complaints from the neighborhood.

In September 1927, Seuphor decided to leave the Parisian milieu for a trip to Spain. After a month’s stopover in Collioure on the Mediterranean coast, where he met the painter Leopold Survage, he stayed in Spain from October to December. There, he discovered the Renaissance artist El Greco. He became fascinated with his work and wrote numerous notes that would become the basis for Greco, his first book on art. This book was written in June 1928 during another stay in Menton, where he was invited by his friend Ingeborg Bjarnason. They shared a house with the photographer Fritz Glarner, whom he had met and frequented in Paris. He had introduced Glarner to Mondrian, and Glarner would later become one of the painter’s disciples and friends during the last years of his life in New York during the Second World War.

Upon his return to Paris in December 1927, Seuphor took back his translator job for radio broadcasts, but this did not prevent him from continuing his travels throughout Europe to meet with personalities of the European avant-garde, notably in Prague, Venice, Brno and Berlin. He also visited the Bauhaus in Dessau. Around that time, his deep friendship with Mondrian, whom he saw daily, led to the creation of Textuel, a painting composed by Mondrian with a poem by Seuphor intertwined in it, and offered to the latter.

1925 – 1928

the European avant-garde

Upon his arrival in Paris, Seuphor survived poorly and stayed at various addresses, notably the Hotel Monaco, rue Champollion, or at the home of the Czech painter Zravy, avenue de Clichy, but also, for a while, at the Salvation Army. In order to overcome a bad cold, on the advice of Theo Van Doesburg (with whom, along with Paul Dermée and Céline Arnauld, there were talks of creating a new magazine entitled Code, which never saw the light), he spent the summer of 1925 at the Hostellerie des Cormorans in Kervilahouen at Belle-île-en-mer, run by Mr. Ratel, a friend and protector of artists. This stay allowed him to write his first poems of verbal music, which were published in 1926 in a collection entitled Diaphragme intérieur et un drapeau. At the end of the year, he left for Menton, where he met George Vantongerloo and learned Italian to prepare for a trip to Naples.

In early 1926, Seuphor went to Italy. He visited Paestum, Naples, Rome, and Venice. He joined some of the Futurists he had met in Berlin and strengthened his relationship with certain members of the group, including Cangiullo, Marinetti, Prampolini and Balla. Seuphor hoped to interest Marinetti in joining a project for a ‘world congress of modern art’, but he failed. However, his stay in Rome inspired him, stimulated by Balla, to write L’éphémère est éternel,

a play of ‘theatre-antitheater’, for which Mondrian composed a model of the sets when Seuphor gave him the text to read upon his return to Paris. Unfortunately, the first performance of the play, scheduled in Lyon, was cancelled at the last minute. It was not until 1968 that it was staged for the first time in Milan in Italian, by the experimental group Il Parametro, and then another decade before it was staged in its original French version, in Paris, at the George Pompidou Center, in 1977.

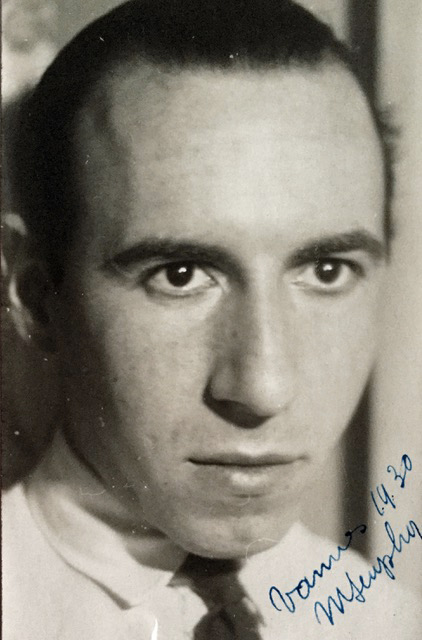

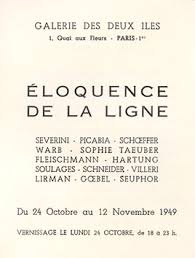

Back in Paris after a detour through Budapest, Seuphor barely survived thanks to a job as translator of foreign radio programs for Parisian newspapers, obtained through Paul Dermée. However, his ambition remained to create a new art magazine. In October, he had a major encounter with Hans Arp (who would sign Jean Arp after the advent of Nazism) and Sophie Taeuber who, along with Mondrian, would become his closest friends. They gave him a camera to help him earn a living by making portraits, but what interested him was the photographer’s eye, not the subject. Thus, he guided the young Hungarian photographer André Kertész through Paris and experimented with photography himself. At this time, he also began to paint néoplastic gouaches. However, his energy was still mainly dedicated to the preparation, with Paul Dermée and Enrico Prampolini, of a new magazine entitled Les documents internationaux de l’esprit nouveau.

The first and only copy (for lack of financing for the following issues) of Les documents internationaux de l’esprit nouveau appeared in 1927. To promote this initiative, Seuphor and Dermée organized a series of eleven literary evenings at the Parisian gallery Le Sacre du Printemps, at 5 rue du Cherche-Midi. Very quickly popular, these evenings brought together artists of the European avant-garde such as Russolo, Pevsner, Mondrian, Léger, the Delaunays, Arp, Marinetti, Tzara, Cocteau, Cendrars, Delteil, Goll, Charchoune, Walden and others. There, Seuphor recited for the first time poems of verbal music such as « Tout en roulant les “R”», which is incorporated in Lecture élémentaire published in 1928. The Sacre du Printemps also hosted an exhibition in which Seuphor and Dermée brought together the works of the Hungarian Ida Thal, the Belgian Victor Delhez, the Dutch typographer and writer Hendrik Nicolaas Werkman, and photographs by André Kertesz. However, at the beginning of June 1927, the owner of the gallery notified them of his decision to put an end to these evenings, following complaints from the neighborhood.

In September 1927, Seuphor decided to leave the Parisian milieu for a trip to Spain. After a month’s stopover in Collioure on the Mediterranean coast, where he met the painter Leopold Survage, he stayed in Spain from October to December. There, he discovered the Renaissance artist El Greco. He became fascinated with his work and wrote numerous notes that would become the basis for Greco, his first book on art. This book was written in June 1928 during another stay in Menton, where he was invited by his friend Ingeborg Bjarnason. They shared a house with the photographer Fritz Glarner, whom he had met and frequented in Paris. He had introduced Glarner to Mondrian, and Glarner would later become one of the painter’s disciples and friends during the last years of his life in New York during the Second World War.

Upon his return to Paris in December 1927, Seuphor took back his translator job for radio broadcasts, but this did not prevent him from continuing his travels throughout Europe to meet with personalities of the European avant-garde, notably in Prague, Venice, Brno and Berlin. He also visited the Bauhaus in Dessau. Around that time, his deep friendship with Mondrian, whom he saw daily, led to the creation of Textuel, a painting composed by Mondrian with a poem by Seuphor intertwined in it, and offered to the latter.

↑

Tout en roulant les "R"

by Michel Seuphor, recorded in 1996•

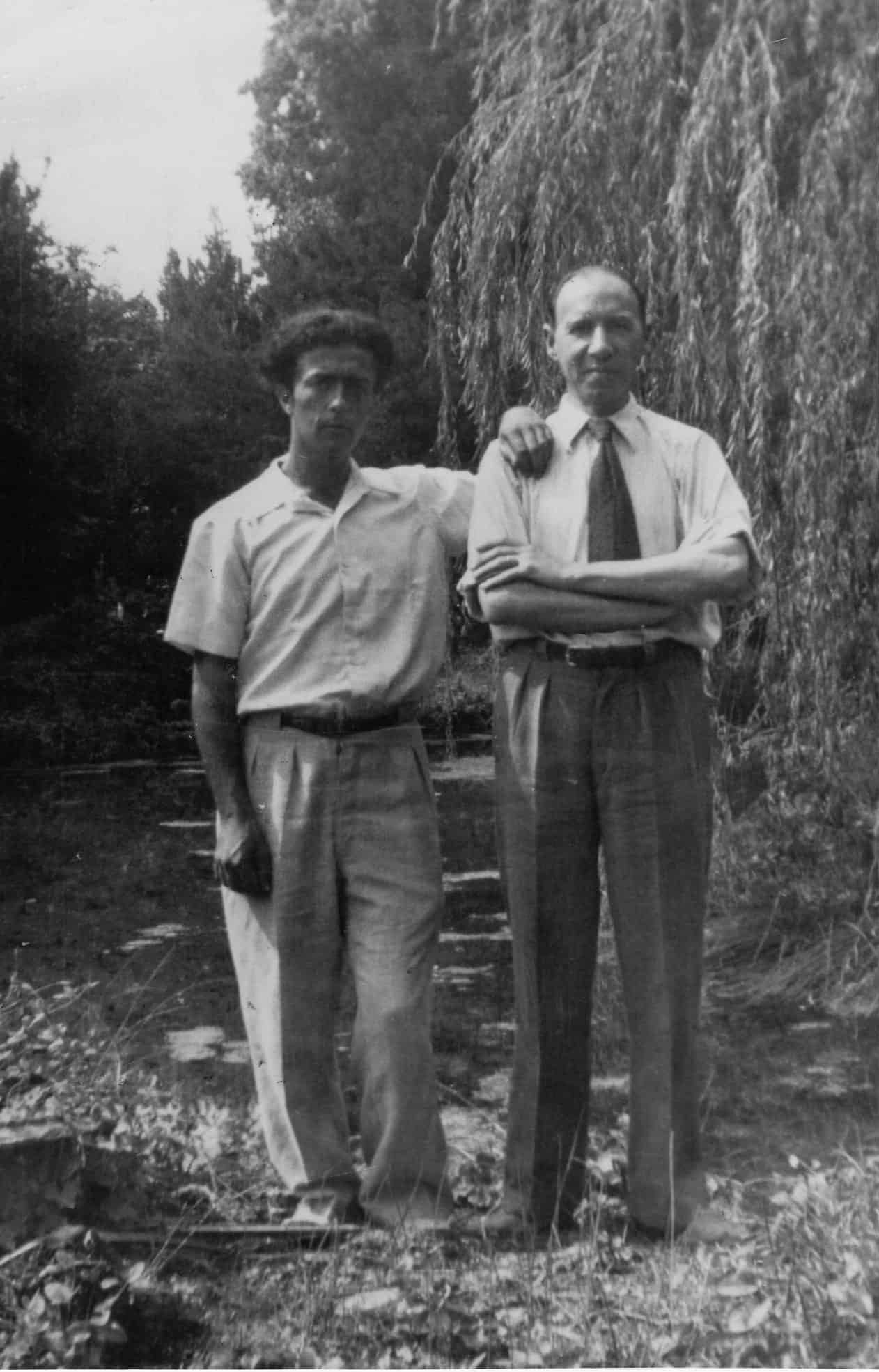

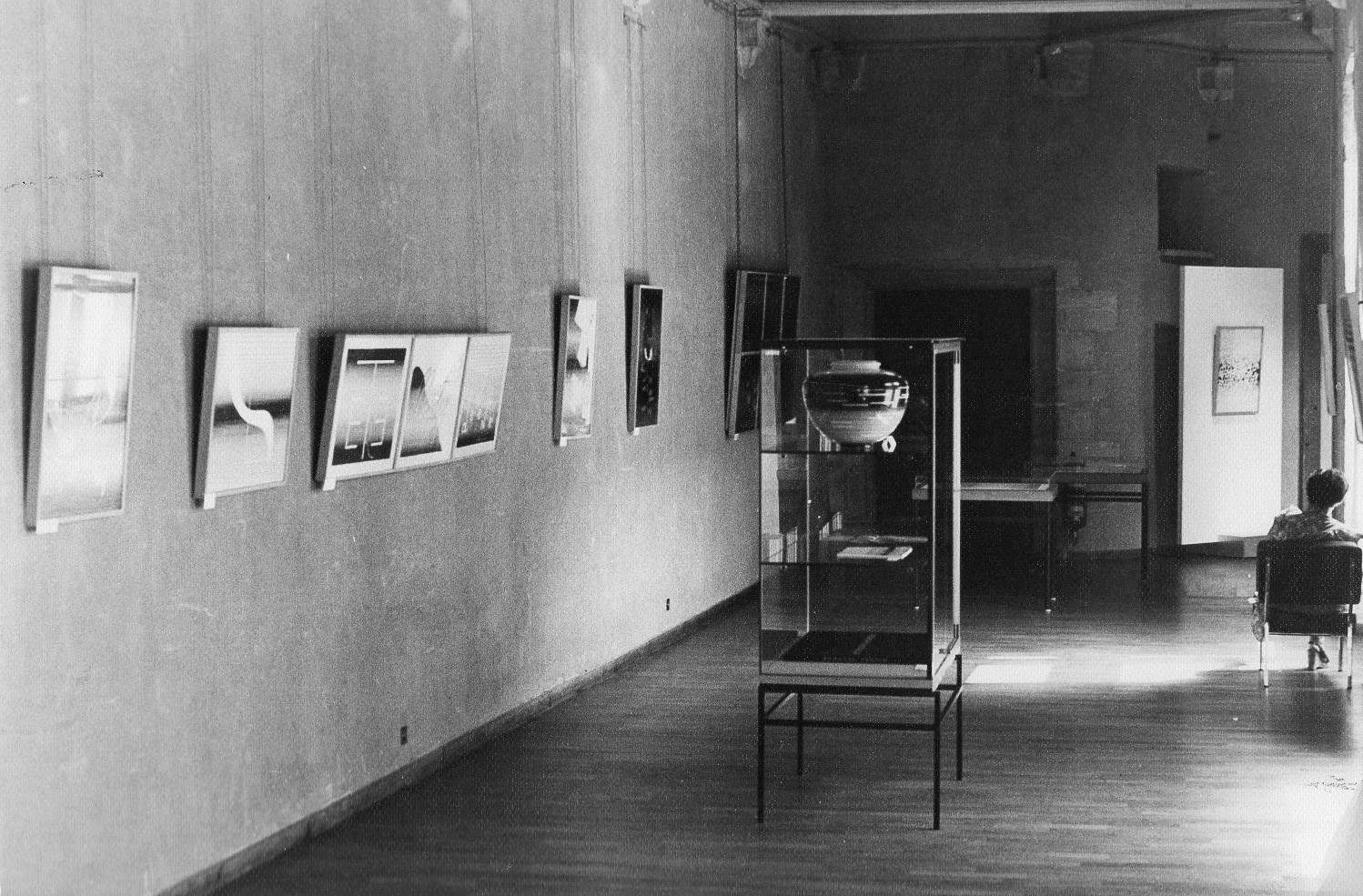

Opening of the exhibition Cercle et Carré

From left to right : Seuphor, Vera Idelson, Georges Vantongerloo, Pierre Daura (behind), Marcelle Cahn, Franciska Clausen,Florence Henri (behind Clausen), Werkman, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Ingeborg Bjarnason, Jean Arp, Piet Mondrian (behind Arp), Nadia Chodasiewicz-Grabowska, Luigi Russolo, Wanda Wolska, Joaquín Torres García (in the middle in front), Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart (to the right of Torres García), Stefan Mosczyrisi, Jean Gorin, Manolita Piña de Torres García and Germán Cueto

1929 – 1930

cercle et carré

In 1929, Seuphor met the painter Joachim Torres García at the Povolotzky Gallery, where he was organizing an exhibition of works by Vordemberge-Gildewart. Seuphor invited him to join informal meetings with Mondrian, Russolo, Vantongerloo and sometimes Arp and Sophie Taeuber, that took place every Sunday in the small apartment where Seuphor lived with his friend Ingeborg Bjarnason in Vanves, a suburb of Paris. Torres García and Seuphor were brought together by the desire, which they shared with all the members of the group, to oppose and defend an alternative to the dominant surrealist movement led by André Breton. This desire was also shared by Theo Van Doesburg, whom they invited to join, but who preferred to create his own, more radical group, Art Concret.

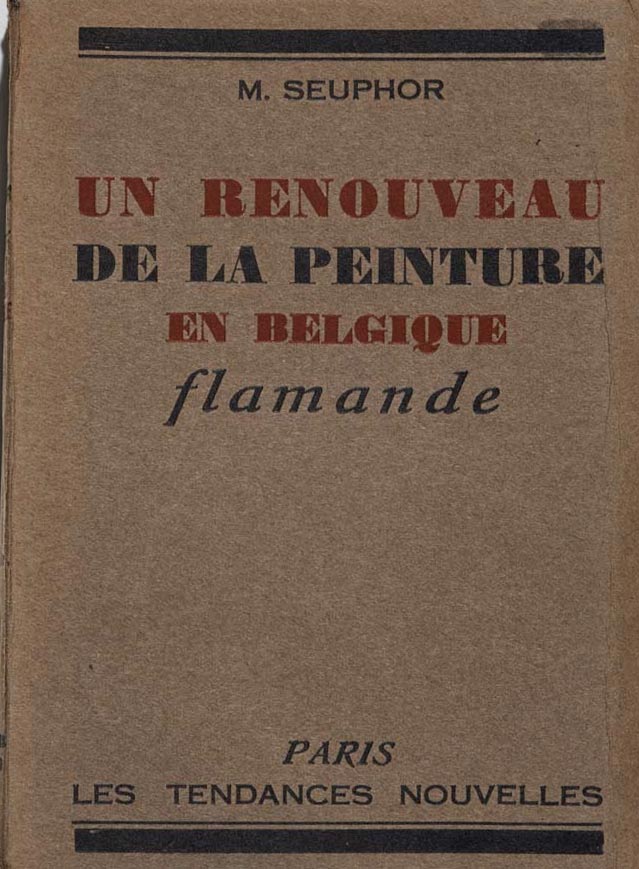

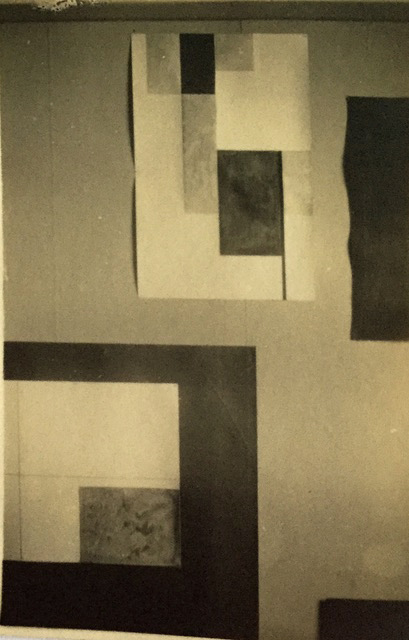

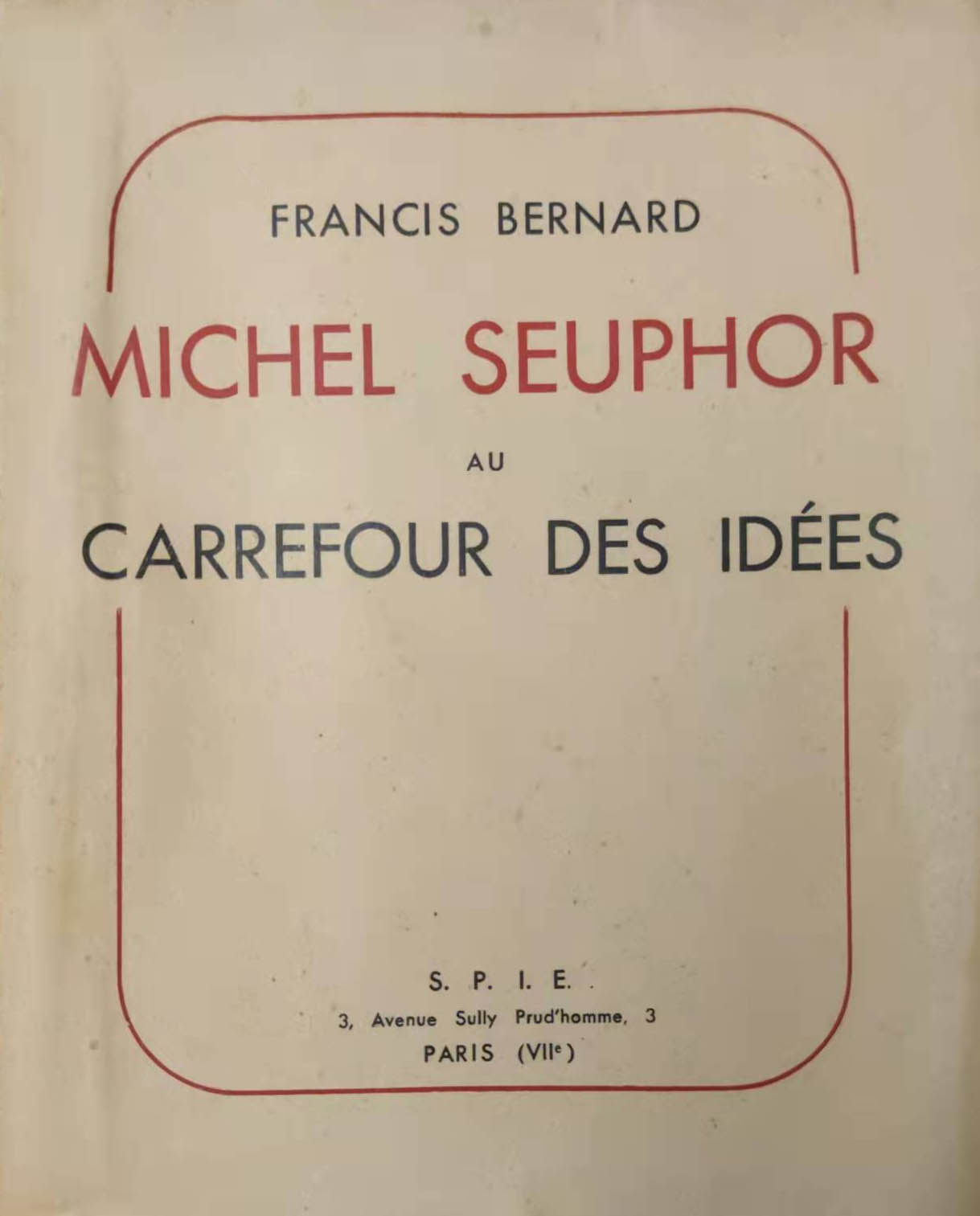

That same year 1929, Seuphor accepted a writing commission for an art book on painting in Flanders, with the promise of a 3,000 franc payment that was timely, even if it resulted in postponing his group projects. He spent the month of July in Belgium visiting artists’ studios and writing the manuscript of Un renouveau de la peinture en Belgique Flamande (A revival of painting in Flemish Belgium). However, the publisher, Szytya, claimed that the result was much too dense compared to what he has expected. In reality, he had gone bankrupt and never paid nor published the volume (Seuphor published it himself in 1932, through his own small publishing house Tendances Nouvelle).

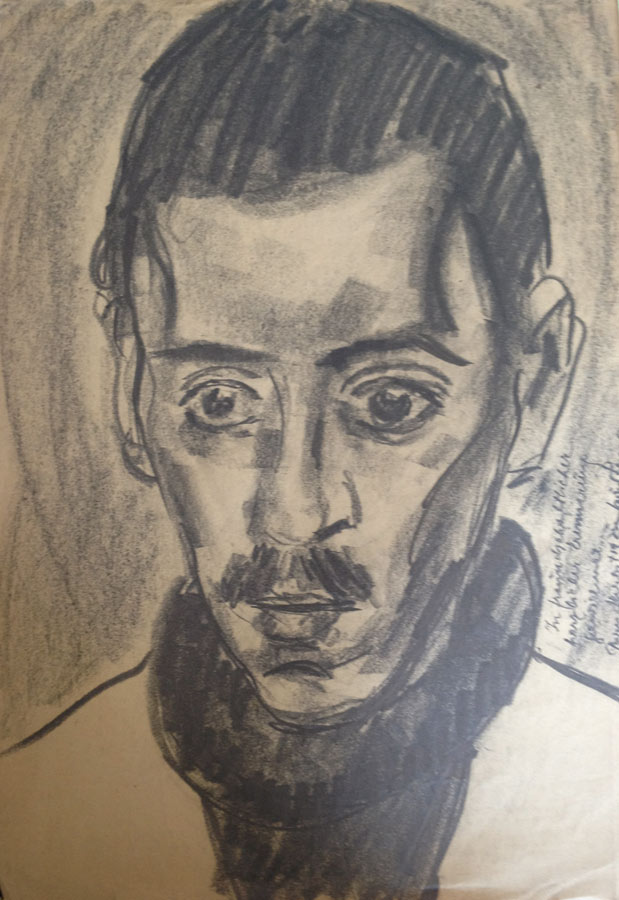

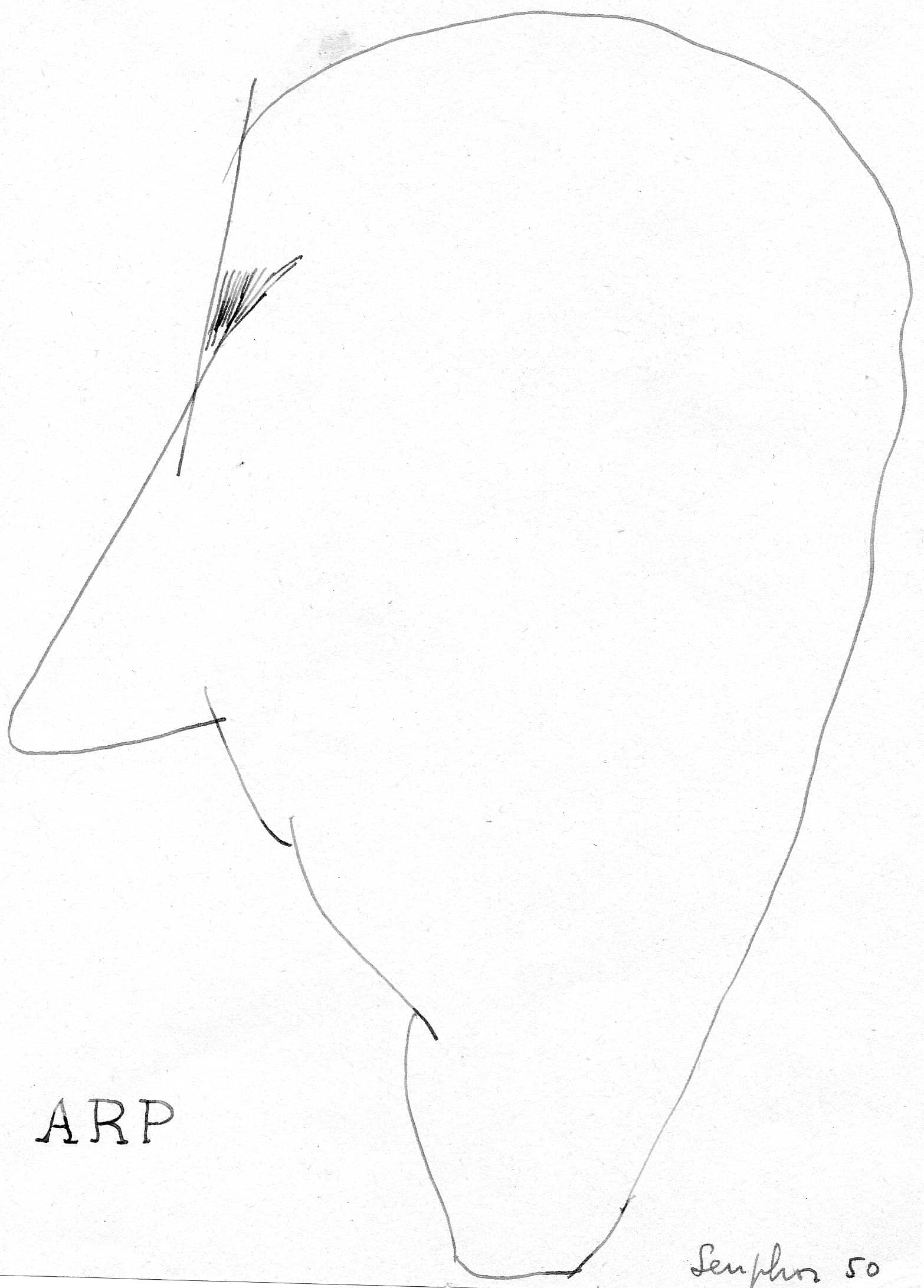

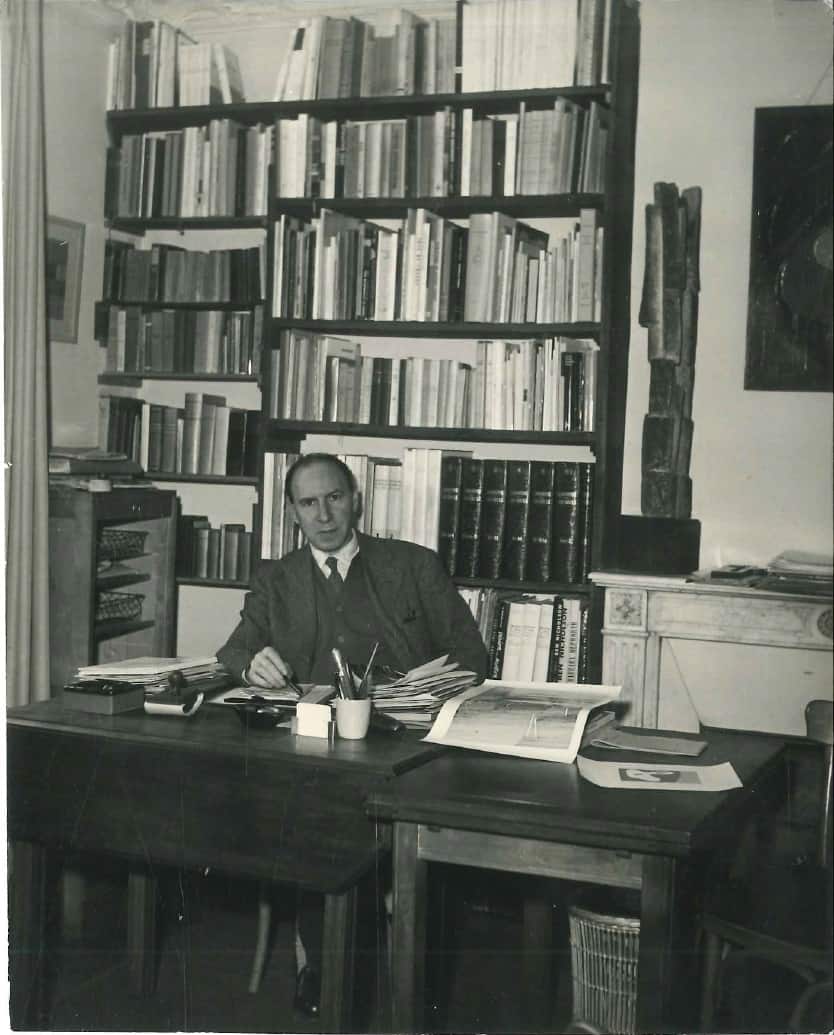

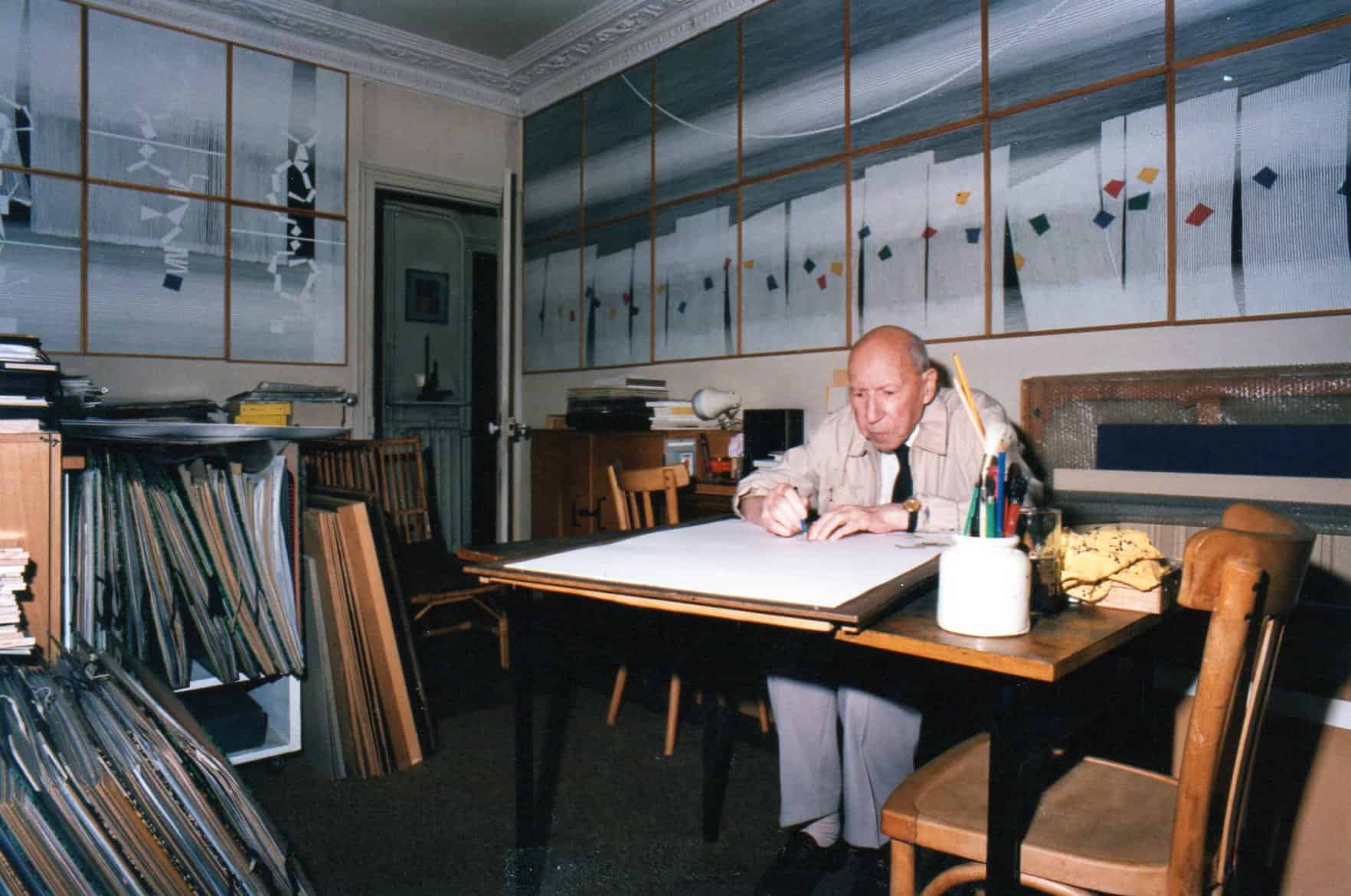

Seuphor’s material life was extremely difficult. To survive, he made portrait photographs of his artist friends. He was constantly drawing and portraying, as shown by his sketches of artists in Un Renouveau de la peinture en Belgique flamande. During this period, he also produced several gouaches néoplastiques but he rapidly judged them to be too close to Mondrian’s style and abandoned this artistic direction.

From the fall of 1929, the number of artists involved in the avant-garde group project grew. The contacts and friendships that Seuphor had made around the world through Het Overzicht and the evenings at the Sacre du Printemps brought several collaborations, including those of Vantongerloo, Hans Arp, Sophie Taeuber, Mondrian, Baumeister, Moholy-Nagy, Kurt Schwitters and Kandinsky. At the beginning of December 1929, the group moved to the Lipp brasserie. But Seuphor found the place too noisy and, from the end of January, the group of 20 to 30 people (many more members were abroad) occupied a room on the second floor of the Café Voltaire, Place de l’Odéon. This was a strange coincidence for the members who, like Arp and Sophie Taeuber, had been among the first Dadaists at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich in 1916.

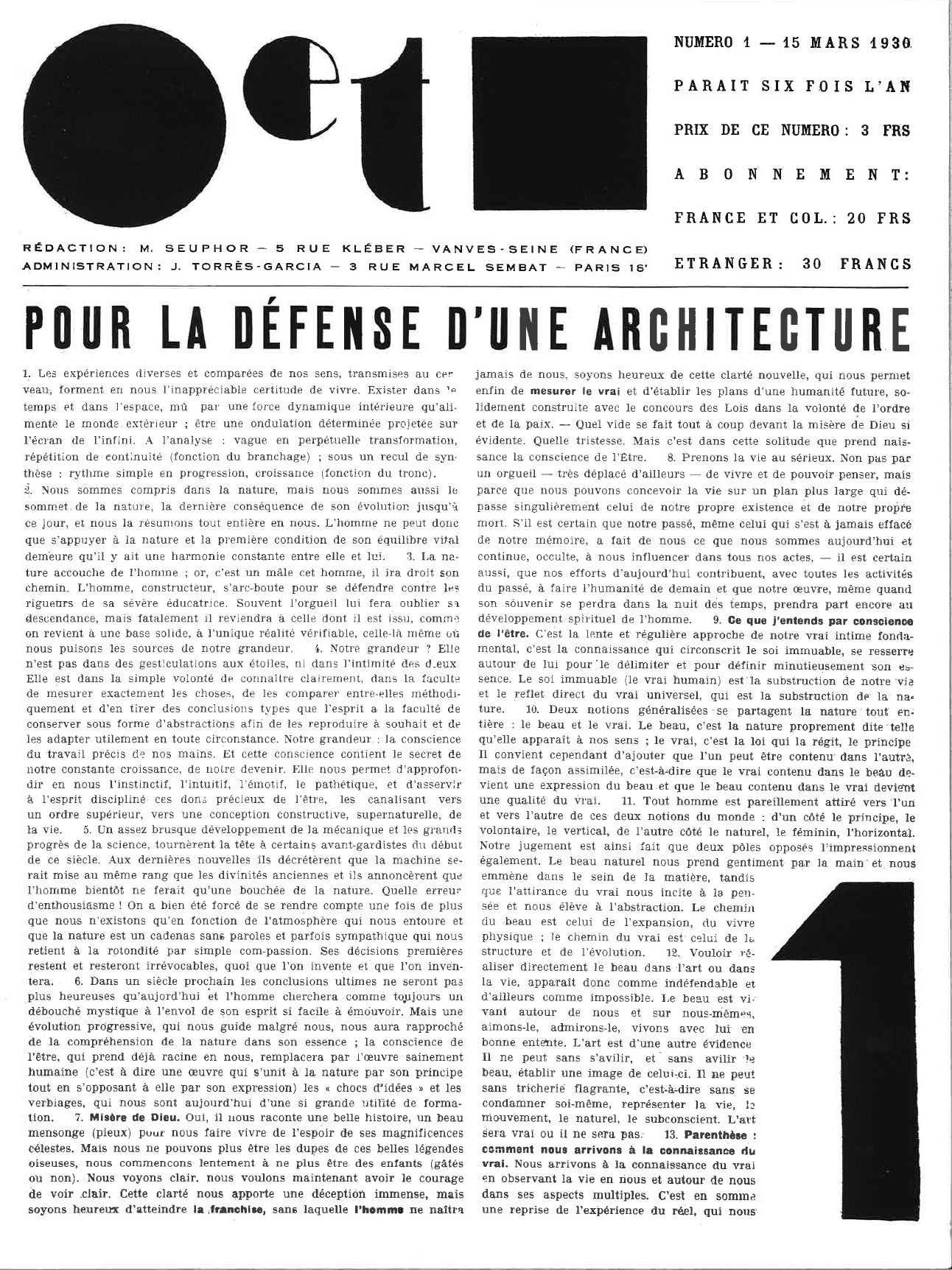

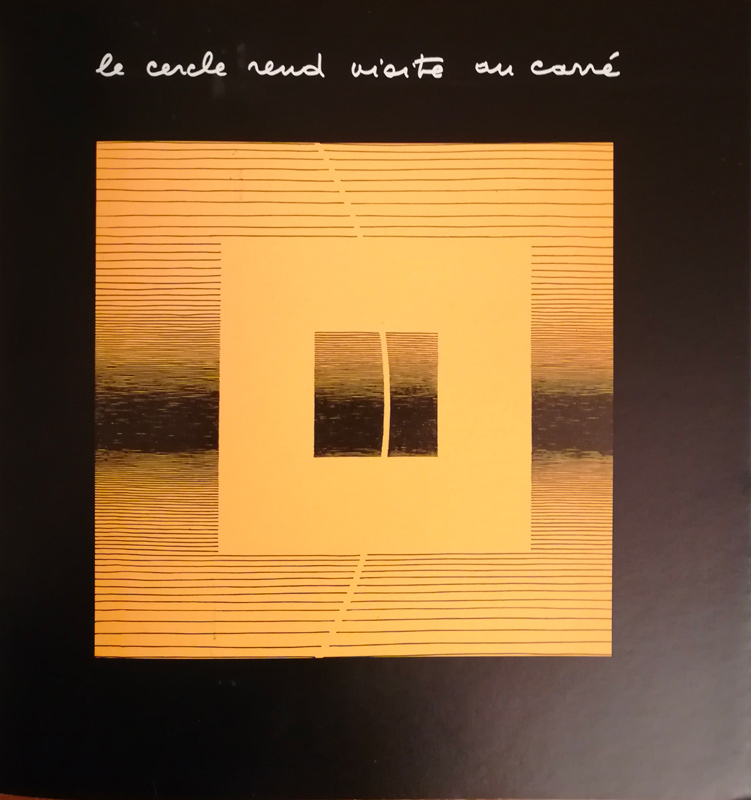

In February 1930, after long and tumultuous discussions, the name Cercle et Carré Circle and Square), proposed by Seuphor, was finally adopted, with a logo created by the painter Daura and the tacit agreement that what was put behind this title would be discussed later. The group entrusted Seuphor with the edition of a magazine of the same name. Indeed, in addition to the experience, he had a talent for writing and the mastery of the French language, which the majority of the artists of the group, who were foreigners, lacked. Three issues were published between March and May 1930 thanks to the collaboration of the Mickums, a Franco-Polish couple owner of the small printing house, Ognisko, rallied to the project through the intermediary of the poet Jan Brzekowski, co-editor of the bilingual magazine L’art contemporain (which was printed there) and contributor to the issues 2 and 3 of Cercle et Carré.

Another project that federated the members of the group very early on was that of an exhibition, which came to fruition in April 1930, at the Galerie 23, rue de la Boétie. Fifty artists of the group, including Arp, Schwitters, Mondrian, Kandinsky, Baumeister, Charchoune, Huszar, Le Corbusier, Léger, Ozenfant, Pevsner, Stazewski, Vordemberge-Gildewart, Sophie Taeuber, Marcelle Cahn, Werkman, Vantongerloo, Gorin, Sartoris, and Torrès-Garcia exhibited one hundred and thirty works. On the closing day, Seuphor gave a lecture on the Poétique Nouvelle (the new poetic). He illustrated his lecture with his poems, which he declaimed behind a metal megaphone mask imagined and forged by Cueto, against a background of music improvised by Russolo on his ‘Russolophone’. This conference attracted a large crowd and was a great success, in contrast with the rest of the exhibition, which had very few visitors. A large excerpt of the lecture was published in the third issue of Cercle et Carré, in June 1930. The group’s meetings continued at the Brasserie Lipp following the closing of the Café Voltaire until the summer, but Torrès-Garcia withdrew due to disagreements regarding the theoretical orientations that Seuphor wanted to follow in the journal.

While preparing the fourth issue of Cercle et Carré and discussing, with Paul Dermée, the publication of a new artistic information magazine that would be entitled Les jours de l’art, Seuphor fell seriously ill with pleurisy in the fall of 1930 and almost died. He was first bedridden in Paris for two months, then his friends gathered funds to send him to a hotel-sanatorium in Grasse. For four months, he stayed there, in daily contact with death. He came out of it alive, but deeply transformed. When he returned to Paris in May 1931, he had to face a very difficult situation: following their separation, his friend Ingeborg had left and emptied the apartment in Vanves. At the same time, he learned of the death of Theo van Doesburg, and the formation of a new group, Abstraction-Création, notably through the action of Georges Vantongerloo, who had used all his contacts during his absence.

1929 – 1931

cercle et carré

In 1929, Seuphor met the painter Joachim Torres García at the Povolotzky Gallery, where he was organizing an exhibition of works by Vordemberge-Gildewart. Seuphor invited him to join informal meetings with Mondrian, Russolo, Vantongerloo and sometimes Arp and Sophie Taeuber, that took place every Sunday in the small apartment where Seuphor lived with his friend Ingeborg Bjarnason in Vanves, a suburb of Paris. Torres García and Seuphor were brought together by the desire, which they shared with all the members of the group, to oppose and defend an alternative to the dominant surrealist movement led by André Breton. This desire was also shared by Theo Van Doesburg, whom they invited to join, but who preferred to create his own, more radical group, Art Concret.

That same year 1929, Seuphor accepted a writing commission for an art book on painting in Flanders, with the promise of a 3,000 franc payment that was timely, even if it resulted in postponing his group projects. He spent the month of July in Belgium visiting artists’ studios and writing the manuscript of Un renouveau de la peinture en Belgique Flamande (A revival of painting in Flemish Belgium). However, the publisher, Szytya, claimed that the result was much too dense compared to what he has expected. In reality, he had gone bankrupt and never paid nor published the volume (Seuphor published it himself in 1932, through his own small publishing house Tendances Nouvelle).

Seuphor’s material life was extremely difficult. To survive, he made portrait photographs of his artist friends. He was constantly drawing and portraying, as shown by his sketches of artists in Un Renouveau de la peinture en Belgique flamande. During this period, he also produced several gouaches néoplastiques but he rapidly judged them to be too close to Mondrian’s style and abandoned this artistic direction.

From the fall of 1929, the number of artists involved in the avant-garde group project grew. The contacts and friendships that Seuphor had made around the world through Het Overzicht and the evenings at the Sacre du Printemps brought several collaborations, including those of Vantongerloo, Hans Arp, Sophie Taeuber, Mondrian, Baumeister, Moholy-Nagy, Kurt Schwitters and Kandinsky. At the beginning of December 1929, the group moved to the Lipp brasserie. But Seuphor found the place too noisy and, from the end of January, the group of 20 to 30 people (many more members were abroad) occupied a room on the second floor of the Café Voltaire, Place de l’Odéon. This was a strange coincidence for the members who, like Arp and Sophie Taeuber, had been among the first Dadaists at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich in 1916.

In February 1930, after long and tumultuous discussions, the name Cercle et Carré Circle and Square), proposed by Seuphor, was finally adopted, with a logo created by the painter Daura and the tacit agreement that what was put behind this title would be discussed later. The group entrusted Seuphor with the edition of a magazine of the same name. Indeed, in addition to the experience, he had a talent for writing and the mastery of the French language, which the majority of the artists of the group, who were foreigners, lacked. Three issues were published between March and May 1930 thanks to the collaboration of the Mickums, a Franco-Polish couple owner of the small printing house, Ognisko, rallied to the project through the intermediary of the poet Jan Brzekowski, co-editor of the bilingual magazine L’art contemporain (which was printed there) and contributor to the issues 2 and 3 of Cercle et Carré.

Another project that federated the members of the group very early on was that of an exhibition, which came to fruition in April 1930, at the Galerie 23, rue de la Boétie. Fifty artists of the group, including Arp, Schwitters, Mondrian, Kandinsky, Baumeister, Charchoune, Huszar, Le Corbusier, Léger, Ozenfant, Pevsner, Stazewski, Vordemberge-Gildewart, Sophie Taeuber, Marcelle Cahn, Werkman, Vantongerloo, Gorin, Sartoris, and Torrès-Garcia exhibited one hundred and thirty works. On the closing day, Seuphor gave a lecture on the Poétique Nouvelle (the new poetic). He illustrated his lecture with his poems, which he declaimed behind a metal megaphone mask imagined and forged by Cueto, against a background of music improvised by Russolo on his ‘Russolophone’. This conference attracted a large crowd and was a great success, in contrast with the rest of the exhibition, which had very few visitors. A large excerpt of the lecture was published in the third issue of Cercle et Carré, in June 1930. The group’s meetings continued at the Brasserie Lipp following the closing of the Café Voltaire until the summer, but Torrès-Garcia withdrew due to disagreements regarding the theoretical orientations that Seuphor wanted to follow in the journal.

While preparing the fourth issue of Cercle et Carré and discussing, with Paul Dermée, the publication of a new artistic information magazine that would be entitled Les jours de l’art, Seuphor fell seriously ill with pleurisy in the fall of 1930 and almost died. He was first bedridden in Paris for two months, then his friends gathered funds to send him to a hotel-sanatorium in Grasse. For four months, he stayed there, in daily contact with death. He came out of it alive, but deeply transformed. When he returned to Paris in May 1931, he had to face a very difficult situation: following their separation, his friend Ingeborg had left and emptied the apartment in Vanves. At the same time, he learned of the death of Theo van Doesburg, and the formation of a new group, Abstraction-Création, notably through the action of Georges Vantongerloo, who had used all his contacts during his absence.

•

Opening of the exhibition Cercle et Carré

From left to right : Seuphor, Vera Idelson, Georges Vantongerloo, Pierre Daura (behind), Marcelle Cahn, Franciska Clausen,Florence Henri (behind Clausen), Werkman, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Ingeborg Bjarnason, Jean Arp, Piet Mondrian (behind Arp), Nadia Chodasiewicz-Grabowska, Luigi Russolo, Wanda Wolska, Joaquín Torres García (in the middle in front), Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart (to the right of Torres García), Stefan Mosczyrisi, Jean Gorin, Manolita Piña de Torres García and Germán Cueto

1930 – 1934

conversion and mariage

Back in Paris, Seuphor found work (as a proofreader), friendship and health thanks to the Mickums, who had printed Cercle et Carré, and who saved him from starvation. Seuphor printed his work le Greco, on their presses, and published it with the publishing house he created himself to this end, Les tendances Nouvelles. It met with some success. Together with Jan Brzekowski, Seuphor also actively contributed to the creation of one of the first museum sections for abstract art in Europe, in the Museum of Lódz, notably by donating works from his personal collection. He briefly participated in Abstraction-Création by producing a text for the first issue of the magazine, which appeared in 1932. Un renouveau de la peinture en Belgique Flamande appeared a little later that year and provoked strong reactions in Belgium, including a definitive rupture in his friendship with Paul Joostens.

For reasons that he will never know, Seuphor had to leave the printing house. He found another job as a conveyor belt for washing machines thanks to his Swiss poet friend Aloïs Bataillard. It was a period of hunger, when he often had to go without food for several days in a row. However, he had in him the desire of writing of a book gathering his first essays on the metaphysics of art and; he already had the title: Le style et le cri. In June 1932, he gave his job up for an invitation to join a six-week writing residency at the Château de la Sarraz in Switzerland. However, it turned out to be a big disappointment for him, as the owner of the place refused to let her guests do any work. It was therefore only after several months of wandering that he finally got to work on his book thanks to the hospitality of the Dr. Miéville, a friend of the architect Alberto Sartoris, in his home in Vevey, Switzerland, from November 1932 to February 1933.

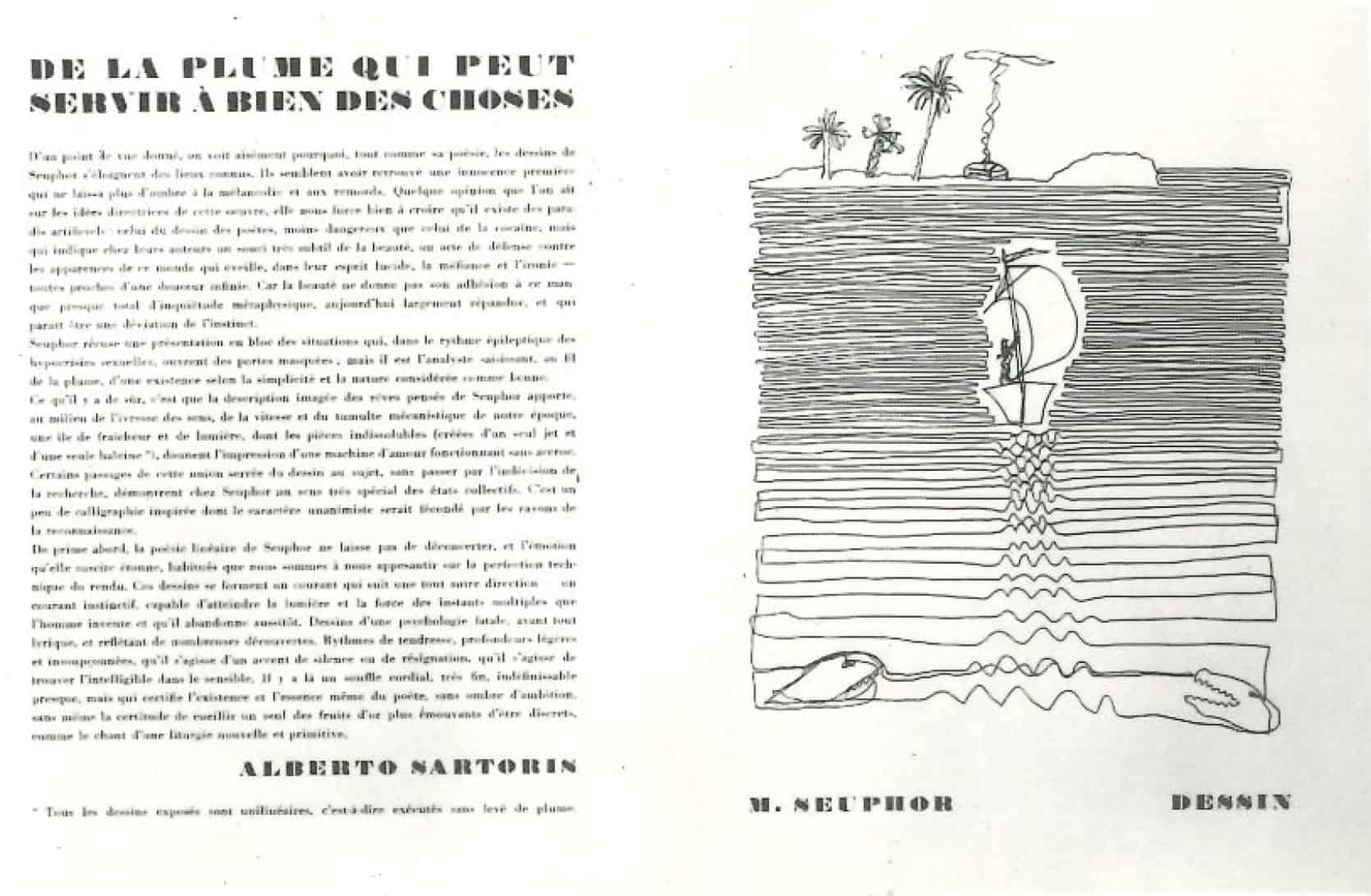

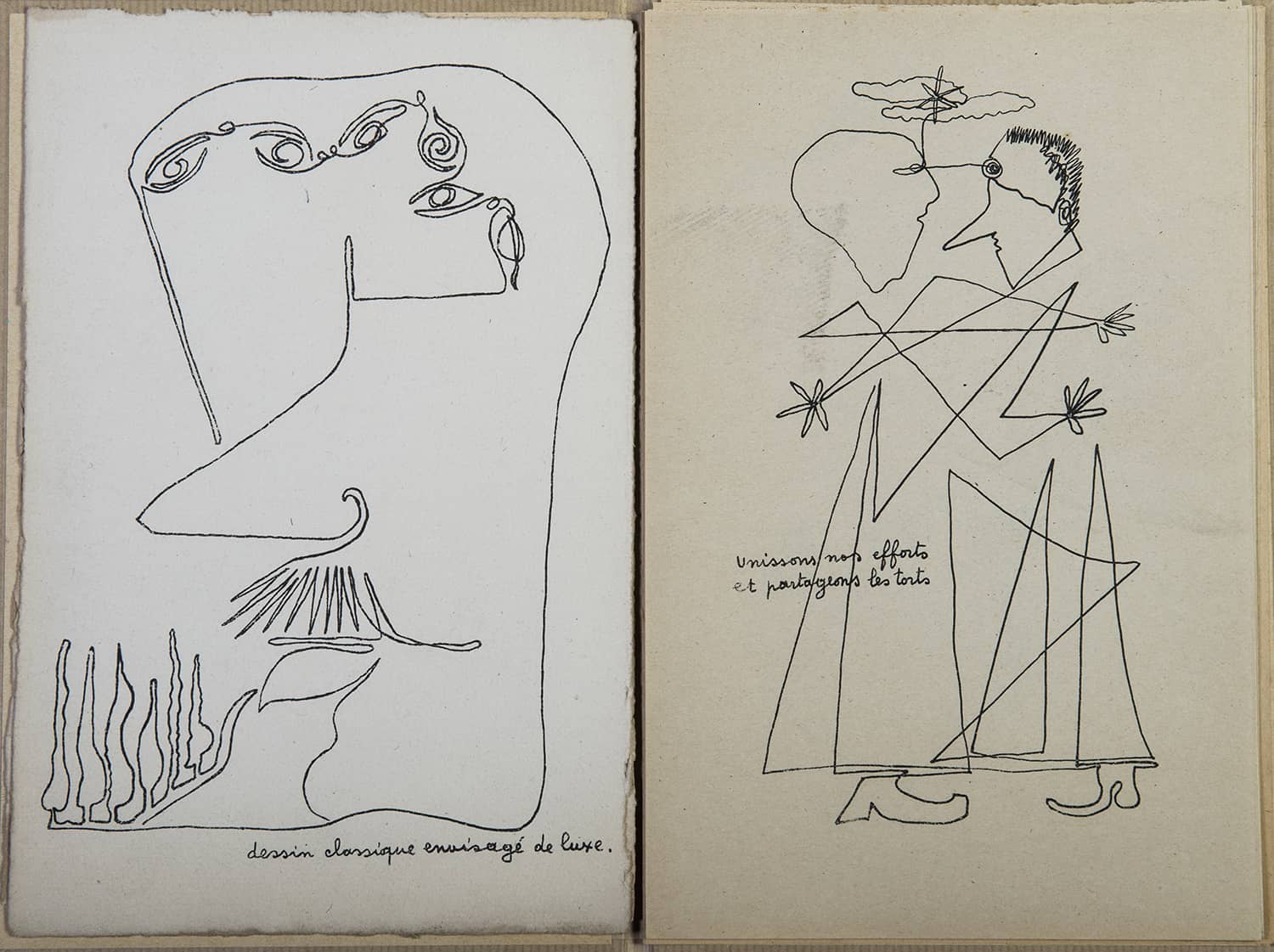

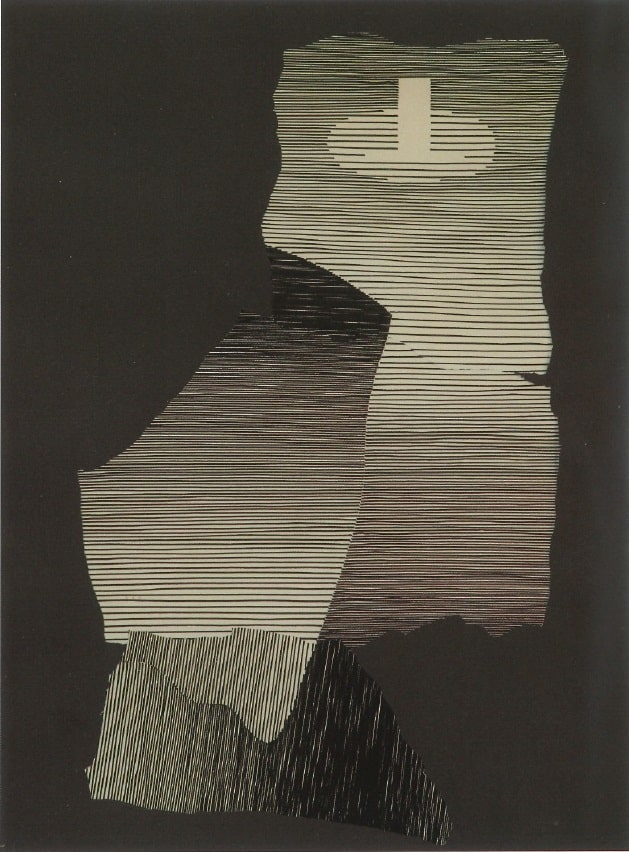

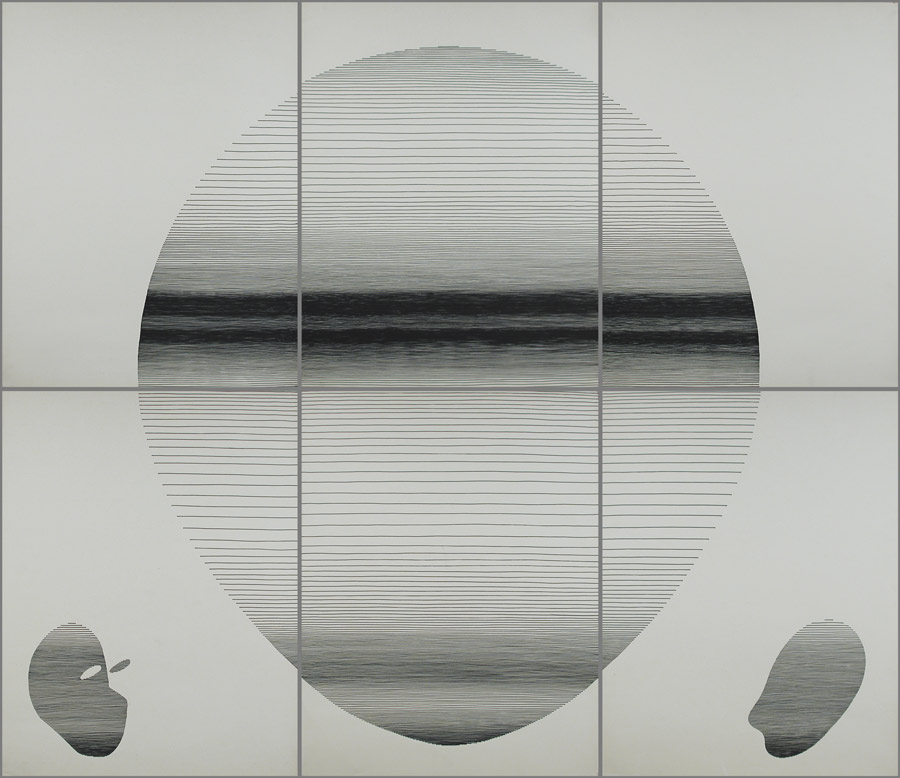

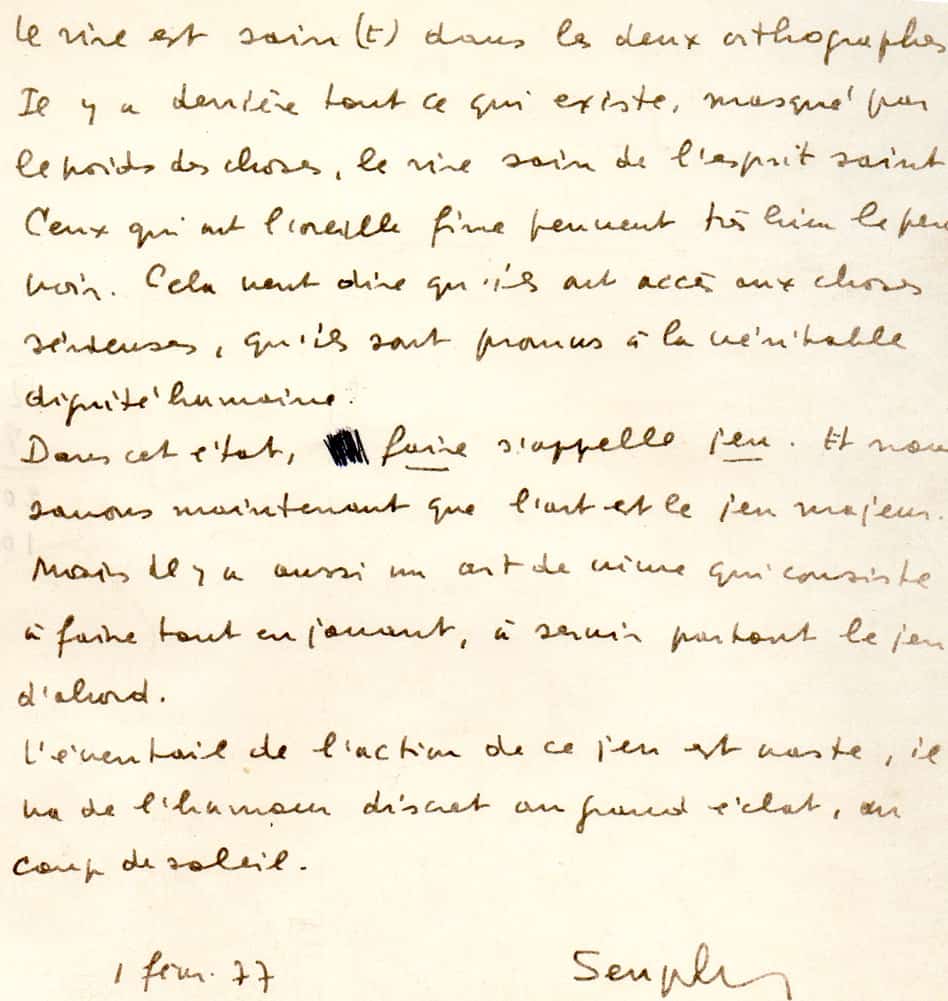

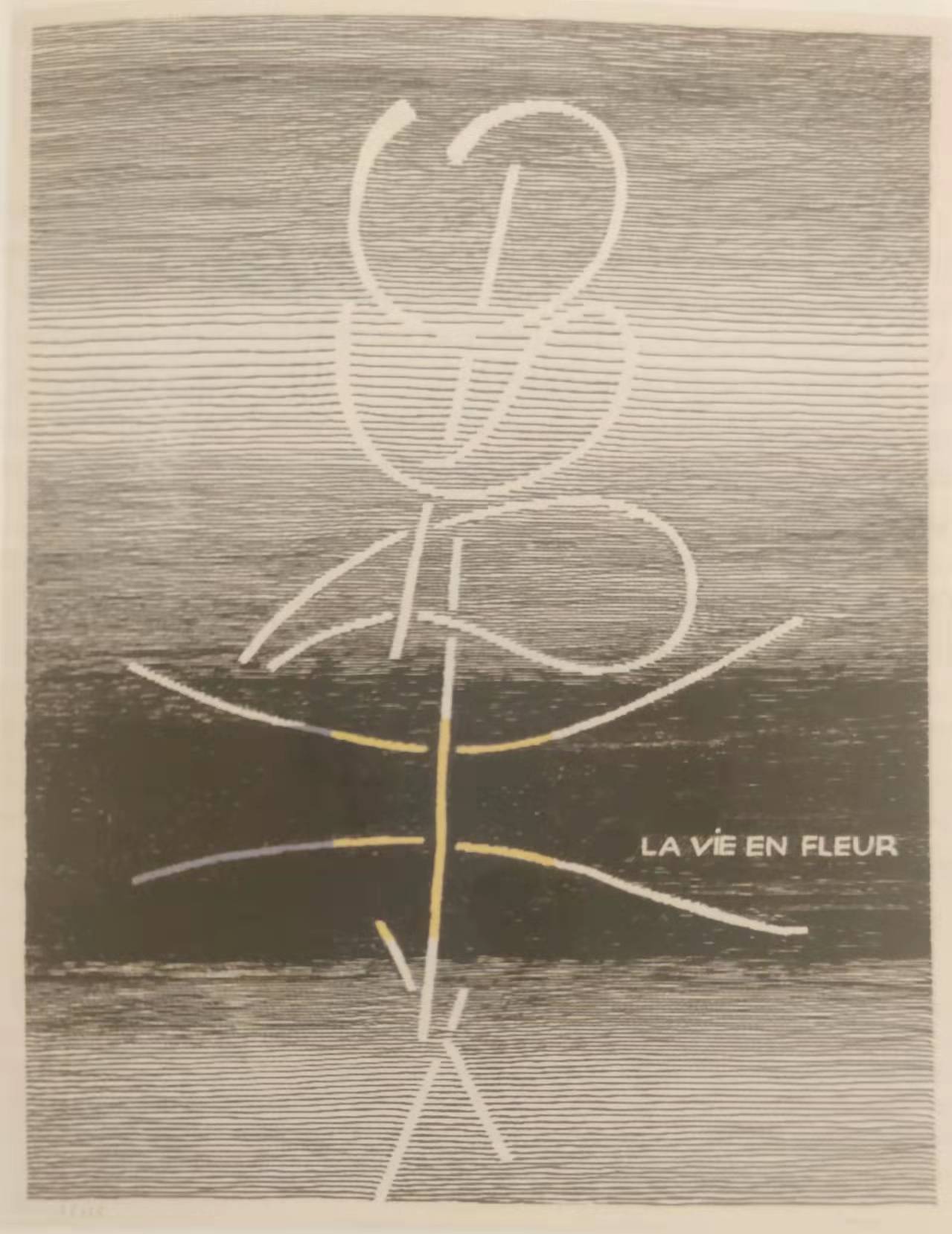

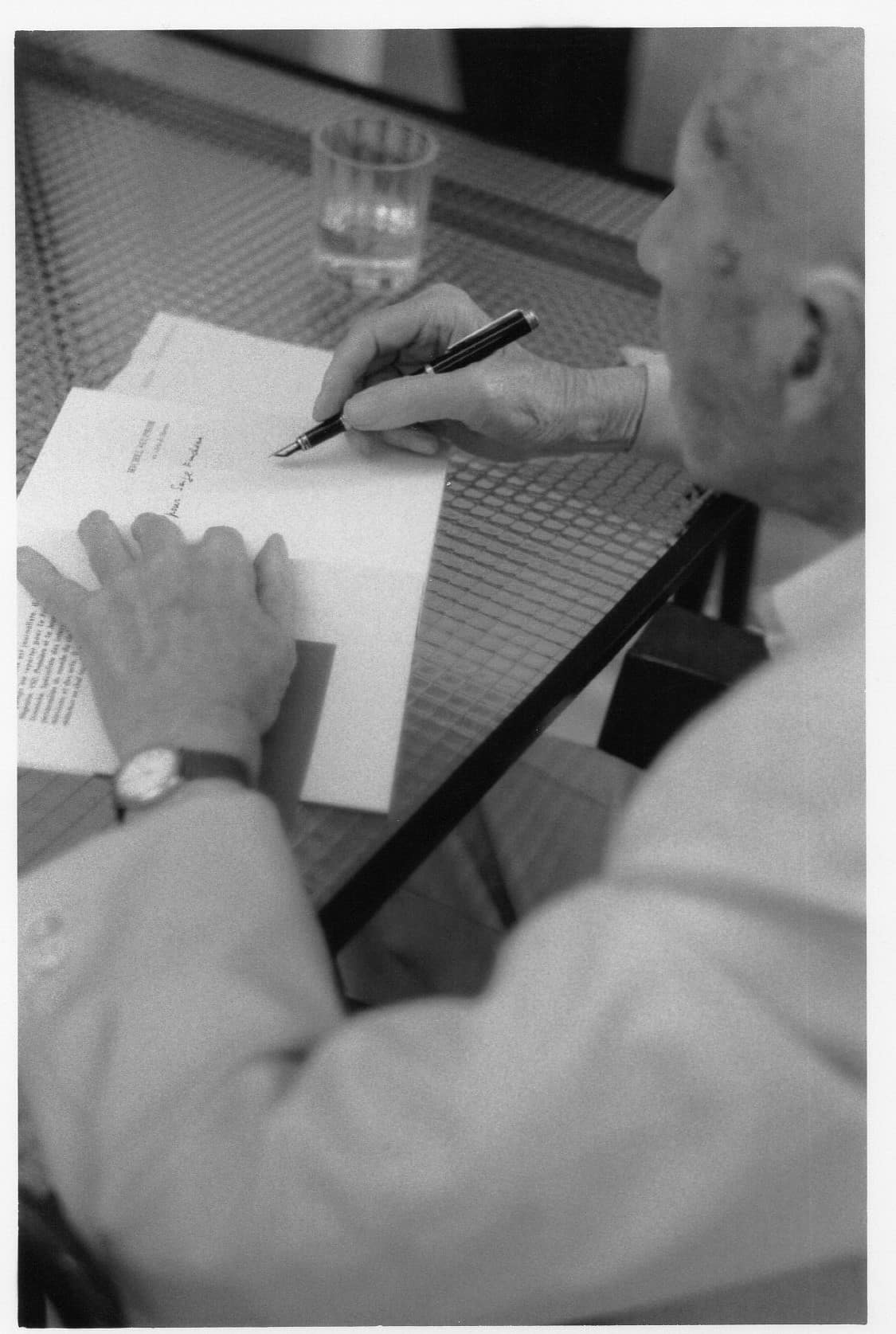

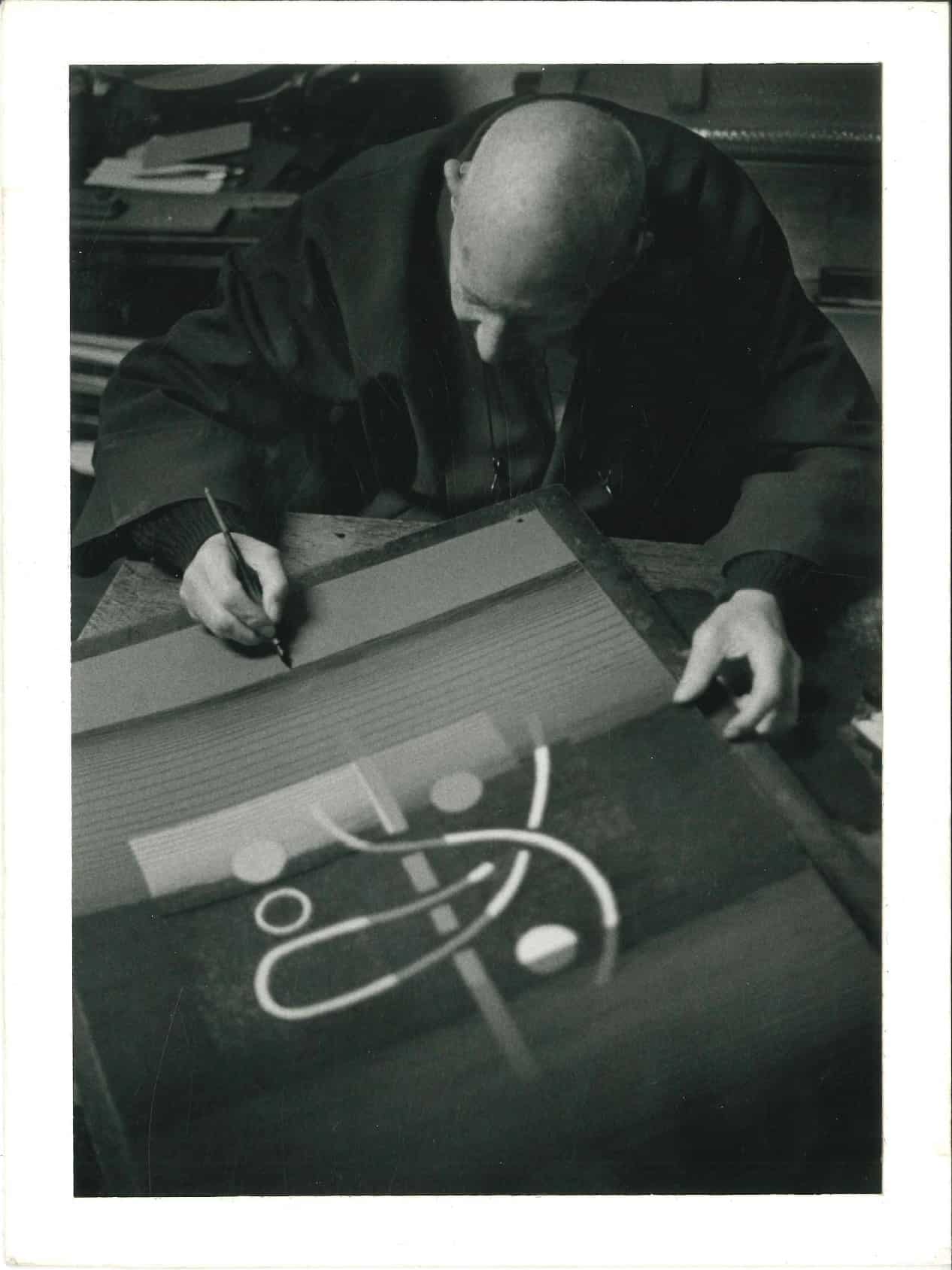

Seuphor wrote intensely for three months, and in the evenings, to relax, he let his pen drift across his white sheets, invaded both by fatigue and the smoke of his cigar. It is in this atmosphere that his first dessins unilinéaires (unilinear drawings) appeared. One day, Sartoris discovered them and had them entrusted to him by Seuphor to be exhibited at the Manassero Gallery in Lausanne, as part of an exhibition dedicated to him in response to the scandal that his sober and pure modernist architecture of the Church of Lourtier had triggered. Seuphor actively contributed to the defense of this ill-received architecture by writing and publishing Sartoris, Architecture du sentiment.

Sartoris, for his part, prefaced the exhibition of Seuphor’s drawings with a text entitled De la Plume qui sert à bien des choses. The book of Seuphor, however, never appeared in the form in which he had envisaged. Only reworked excerpts were published, such as the article Le cri du temps présent published in the journal Esprit in 1933, Style published by the Swiss journal Nova Vetera in 1934 and, Le cri est dans le Cœur, published in 1945 in the journal Résurrection.

During the following months, Seuphor did not earn enough to support himself and owed it to the friendship and admiration of a few people for his writings to continue his travels, constantly seeking the right place to write. He had many disappointments, such as his stay in Moly-Sabata (near Lyon), which he cut short in disgust at the casteist and pro-Nazi speeches of his hosts. However, it was there that he became friends with Jacques Plasse, his future brother-in-law. As soon as he returned to Paris, he went to Jacques’ parents to give them news about their son. The parents Plasse were welcoming and immediately sympathized with the young poet, whom they invite to their table. Seuphor met their second daughter, Suzanne, with whom he began to develop a deep friendship.

In Paris, Seuphor stayed for several months in a miserable room in the Hotel du Luxembourg, next door to that of the poet Edmond Humeau, who proved to be a connoisseur and admirer of his writings. Humeau exchanges his 2514 pages missal for a copy of Lecture élémentaire. Suzanne Plasse, who had become a fervent admirer of Seuphor, helped him by typing his texts on her typewriter, bringing him her cheerfulness and often dishes prepared at home. Around that time, Seuphor also learned of the untimely death of Alice Nahon, a Flemish poetess with whom he had had a romance in the early twenties, and with whom he had renewed contact during his stay in Grasse.

A profound change took place in Seuphor during these years of tribulations and material misery.

“I had entered a quite particular phase of my life, in this disguised sanatorium in Grasse, and was moving toward what Bergson called ʺ the immanence of transcendence ʺ. Reading Schopenhauer had taught me a lot as well as Buddhism and the sages of China, Lao Tzu, Chouang Tzu. Little by little, a total disaffection from external life was taking place in me.” (Une vie à angle droit, 1988)

With Edmond Humeau’s voluminous missal as only book, Seuphor spent the summer of 1933 in Théoule-sur-mer at the Dutch philosopher and friend of Mondrian, Louis Hoyack. Despite differences of political opinion that earned him the wrath of his host (who turned out to be a follower of National Socialism), Seuphor wrote nearly 150 essays, from which the philosopher Jacques Maritain selected a few for publication (although they were not published until 1944 under the title Informations). At the same time, the reading of the missal put Seuphor back in touch with the very pure faith of his childhood and the Catholic religion in which he began to seek an inner direction that corresponded to his new aspirations.

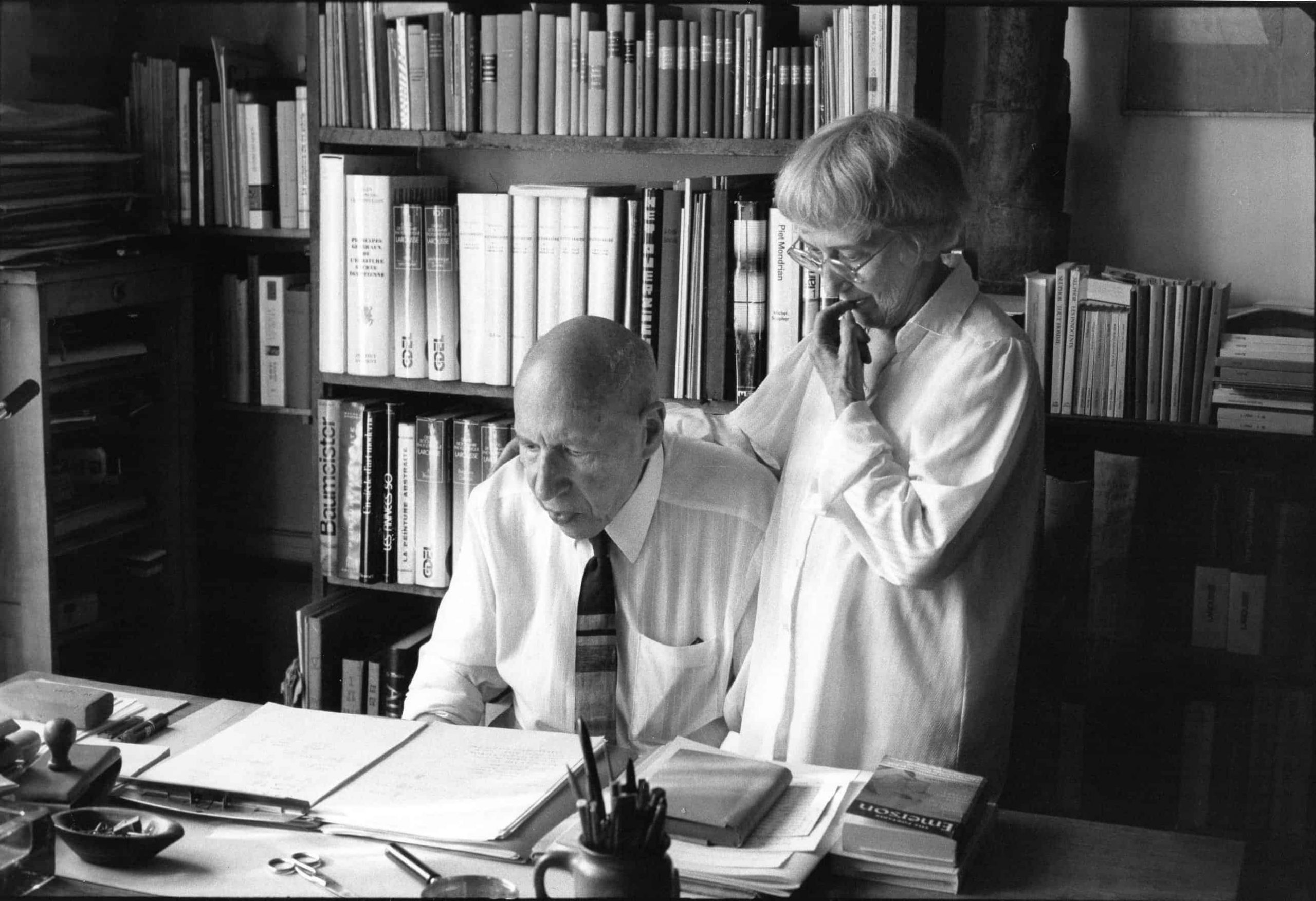

Suzanne went to Théoule-sur-mer several times and, during one of her visits, Seuphor asked her to marry him. Suzanne accepted. She was a determined young woman who was completely won over to Seuphor’s love. Back in Paris in October, Seuphor got a job as a secretary at the Semaine de Paris, then as a night proofreader at the daily newspaper Aujourd’hui. This well-paid job, as well as Suzanne’s job as a secretary at the Red Cross, allowed them to make some savings. During these months, Seuphor wrote poems that he would publish two years later with Corréa under the title: Dans le Royaume du cœur. He contributed to the magazine Esprit and, in addition to his article on Le cri du temps présent, he also published a French translation of L’évasion du monastère Lama, by Joseph-Albert Otto, which allowed him to make an incursion into the Buddhist universe.

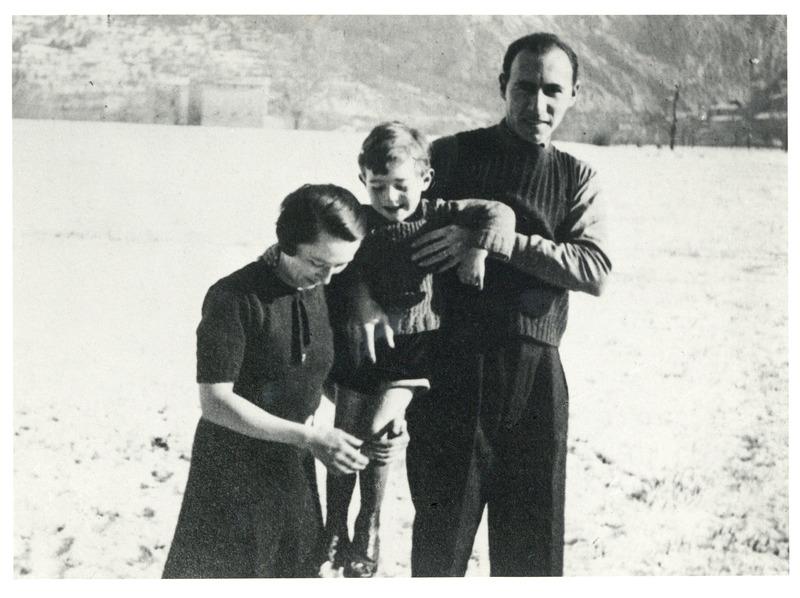

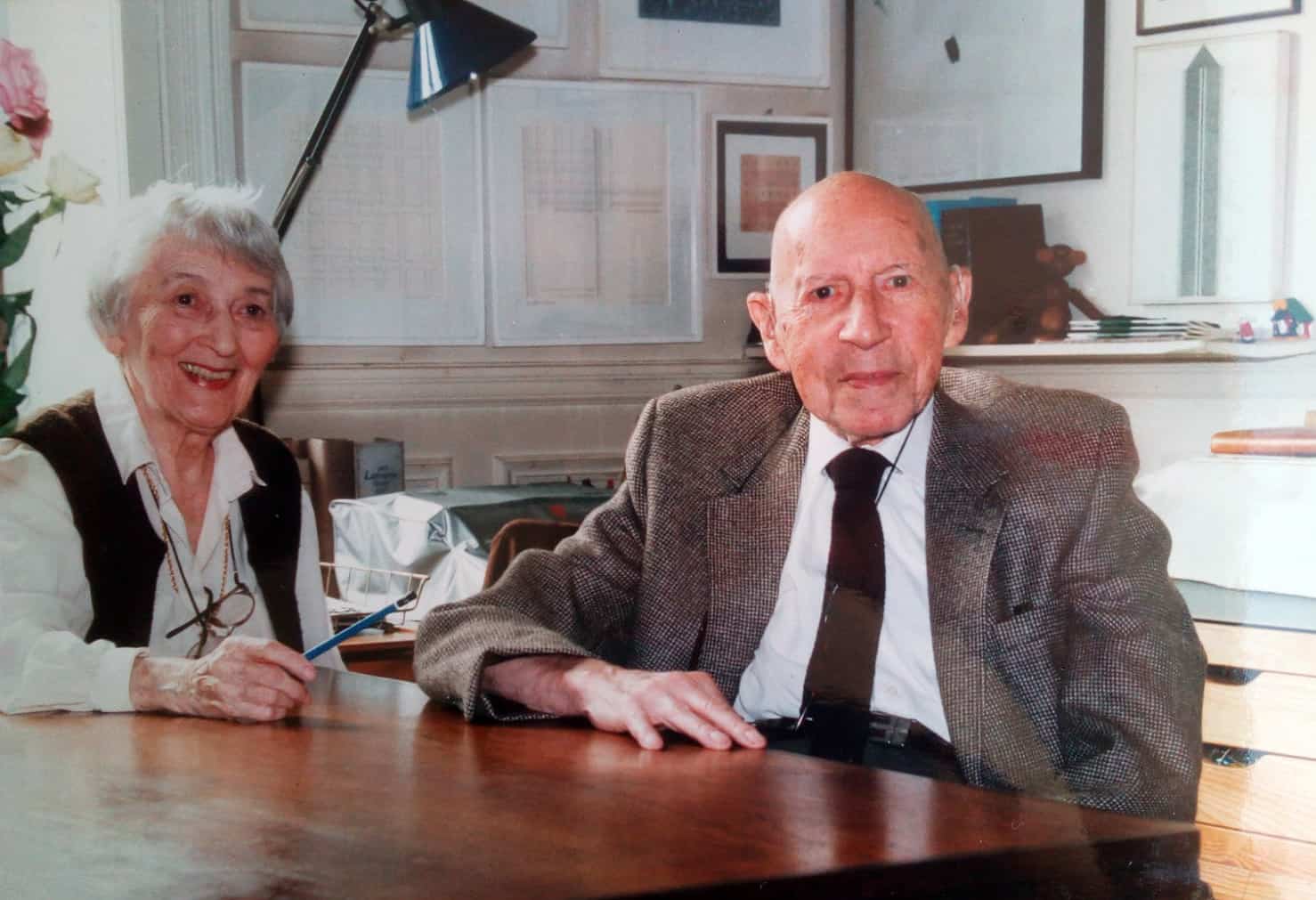

Suzanne Plasse and Fernand Berckelaers, alias Michel Seuphor, got married in Paris on April 19, 1934 and left for the south right away afterward.

“I hated Paris and all the noise. I wanted to go away as far as possible and never come back. (…) I was entering an atmosphere of pure spirituality, and to live it, I needed a convent, the countryside or a kind of desert, but with someone (…) Suzanne was willing to accompany me in this singular adventure. It was very risky…” (Une vie à angle droit, 1988.)

1930 – 1934

conversion and mariage

Back in Paris, Seuphor found work (as a proofreader), friendship and health thanks to the Mickums, who had printed Cercle et Carré, and who saved him from starvation. Seuphor printed his work le Greco, on their presses, and published it with the publishing house he created himself to this end, Les tendances Nouvelles. It met with some success. Together with Jan Brzekowski, Seuphor also actively contributed to the creation of one of the first museum sections for abstract art in Europe, in the Museum of Lódz, notably by donating works from his personal collection. He briefly participated in Abstraction-Création by producing a text for the first issue of the magazine, which appeared in 1932. Un renouveau de la peinture en Belgique Flamande appeared a little later that year and provoked strong reactions in Belgium, including a definitive rupture in his friendship with Paul Joostens.

For reasons that he will never know, Seuphor had to leave the printing house. He found another job as a conveyor belt for washing machines thanks to his Swiss poet friend Aloïs Bataillard. It was a period of hunger, when he often had to go without food for several days in a row. However, he had in him the desire of writing of a book gathering his first essays on the metaphysics of art and; he already had the title: Le style et le cri. In June 1932, he gave his job up for an invitation to join a six-week writing residency at the Château de la Sarraz in Switzerland. However, it turned out to be a big disappointment for him, as the owner of the place refused to let her guests do any work. It was therefore only after several months of wandering that he finally got to work on his book thanks to the hospitality of the Dr. Miéville, a friend of the architect Alberto Sartoris, in his home in Vevey, Switzerland, from November 1932 to February 1933.

Seuphor wrote intensely for three months, and in the evenings, to relax, he let his pen drift across his white sheets, invaded both by fatigue and the smoke of his cigar. It is in this atmosphere that his first dessins unilinéaires (unilinear drawings) appeared. One day, Sartoris discovered them and had them entrusted to him by Seuphor to be exhibited at the Manassero Gallery in Lausanne, as part of an exhibition dedicated to him in response to the scandal that his sober and pure modernist architecture of the Church of Lourtier had triggered. Seuphor actively contributed to the defense of this ill-received architecture by writing and publishing Sartoris, Architecture du sentiment.

Sartoris, for his part, prefaced the exhibition of Seuphor’s drawings with a text entitled De la Plume qui sert à bien des choses. The book of Seuphor, however, never appeared in the form in which he had envisaged. Only reworked excerpts were published, such as the article Le cri du temps présent published in the journal Esprit in 1933, Style published by the Swiss journal Nova Vetera in 1934 and, Le cri est dans le Cœur, published in 1945 in the journal Résurrection.

During the following months, Seuphor did not earn enough to support himself and owed it to the friendship and admiration of a few people for his writings to continue his travels, constantly seeking the right place to write. He had many disappointments, such as his stay in Moly-Sabata (near Lyon), which he cut short in disgust at the casteist and pro-Nazi speeches of his hosts. However, it was there that he became friends with Jacques Plasse, his future brother-in-law. As soon as he returned to Paris, he went to Jacques’ parents to give them news about their son. The parents Plasse were welcoming and immediately sympathized with the young poet, whom they invite to their table. Seuphor met their second daughter, Suzanne, with whom he began to develop a deep friendship.

In Paris, Seuphor stayed for several months in a miserable room in the Hotel du Luxembourg, next door to that of the poet Edmond Humeau, who proved to be a connoisseur and admirer of his writings. Humeau exchanges his 2514 pages missal for a copy of Lecture élémentaire. Suzanne Plasse, who had become a fervent admirer of Seuphor, helped him by typing his texts on her typewriter, bringing him her cheerfulness and often dishes prepared at home. Around that time, Seuphor also learned of the untimely death of Alice Nahon, a Flemish poetess with whom he had had a romance in the early twenties, and with whom he had renewed contact during his stay in Grasse.

A profound change took place in Seuphor during these years of tribulations and material misery.

“I had entered a quite particular phase of my life, in this disguised sanatorium in Grasse, and was moving toward what Bergson called ʺ the immanence of transcendence ʺ. Reading Schopenhauer had taught me a lot as well as Buddhism and the sages of China, Lao Tzu, Chouang Tzu. Little by little, a total disaffection from external life was taking place in me.” (Une vie à angle droit, 1988)

With Edmond Humeau’s voluminous missal as only book, Seuphor spent the summer of 1933 in Théoule-sur-mer at the Dutch philosopher and friend of Mondrian, Louis Hoyack. Despite differences of political opinion that earned him the wrath of his host (who turned out to be a follower of National Socialism), Seuphor wrote nearly 150 essays, from which the philosopher Jacques Maritain selected a few for publication (although they were not published until 1944 under the title Informations). At the same time, the reading of the missal put Seuphor back in touch with the very pure faith of his childhood and the Catholic religion in which he began to seek an inner direction that corresponded to his new aspirations.

Suzanne went to Théoule-sur-mer several times and, during one of her visits, Seuphor asked her to marry him. Suzanne accepted. She was a determined young woman who was completely won over to Seuphor’s love. Back in Paris in October, Seuphor got a job as a secretary at the Semaine de Paris, then as a night proofreader at the daily newspaper Aujourd’hui. This well-paid job, as well as Suzanne’s job as a secretary at the Red Cross, allowed them to make some savings. During these months, Seuphor wrote poems that he would publish two years later with Corréa under the title: Dans le Royaume du cœur. He contributed to the magazine Esprit and, in addition to his article on Le cri du temps présent, he also published a French translation of L’évasion du monastère Lama, by Joseph-Albert Otto, which allowed him to make an incursion into the Buddhist universe.

Suzanne Plasse and Fernand Berckelaers, alias Michel Seuphor, got married in Paris on April 19, 1934 and left for the south right away afterward.

“I hated Paris and all the noise. I wanted to go away as far as possible and never come back. (…) I was entering an atmosphere of pure spirituality, and to live it, I needed a convent, the countryside or a kind of desert, but with someone (…) Suzanne was willing to accompany me in this singular adventure. It was very risky…” (Une vie à angle droit, 1988.)

1934 – 1939

Anduze and the rise of Nazism

The Seuphors first settled for a few months in a little house near Nîmes, lent to them by Léon Marsal, a friend and furniture dealer. The announcement of a forthcoming birth led them to look for a house. They finally found it in Anduze, a Cevennes village that was then half empty. It was rather a ruin that they bought for the modest sum of 1500 francs and that they restored little by little.

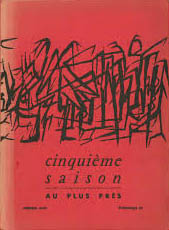

In December 1934, Seuphor created a new magazine: La Nouvelle Campagne. Suzanne typed the 45 copies to which their friends subscribed. They published 30 issues from December 1934 to July 1939. Despite living far from Paris, the Seuphors maintained links and a regular correspondence with the artists and writers that Michel had met in Paris, in particular with the Arps, the Delaunays, Mondrian etc. Seuphor also collaborated regularly with local newspapers, as well as with the weekly magazine Sept published by the Dominican Fathers of Juvisy. The sale of his articles and subscriptions to La Nouvelle Campagne were the main source of income for the household until 1937.

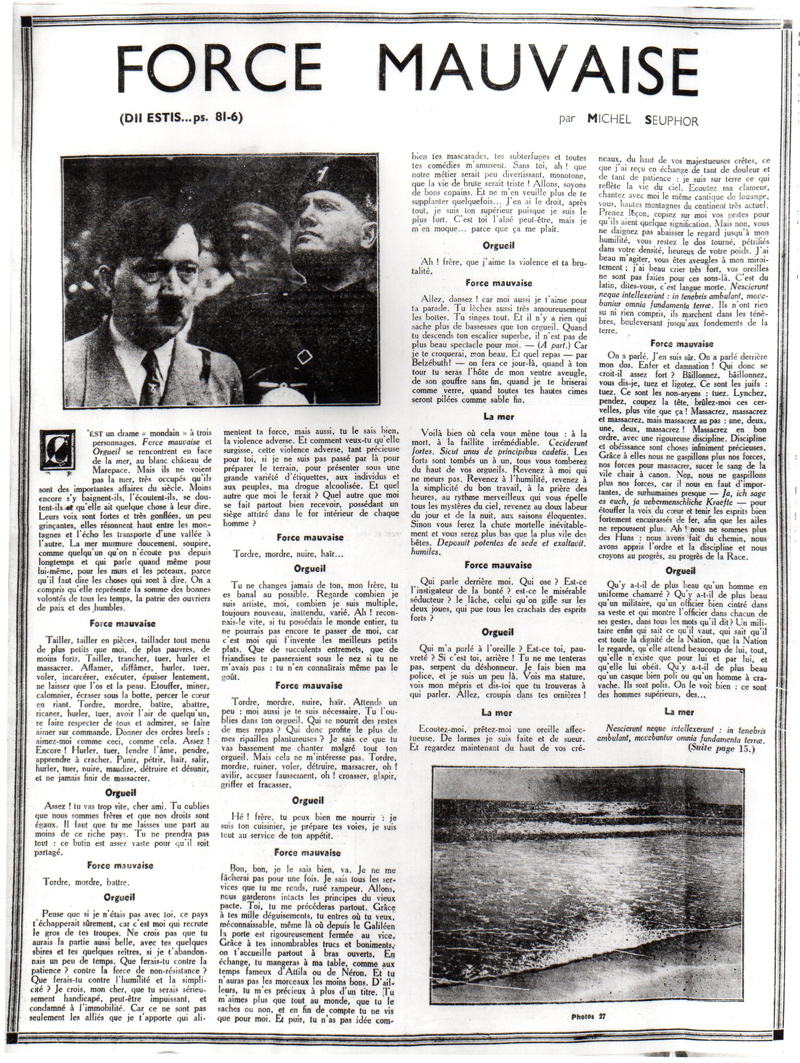

Seuphor published there his reflections on social issues, his poems, as well as political articles in which he denounced, among others, Hitler and Mussolini, communism and fascism. One of his articles, entitled Force Mauvaise in reaction to the invasion of Ethiopia by Mussolini, appeared in Sept. 20, 1935. It is a fictitious dialogue between Hitler (alias Force Mauvaise /Evil force) and Mussolini (alias Orgueil / Pride) – at the time they had not yet met – in which he makes them discuss the fate of Europe. Seuphor chose to illustrate his article with a photomontage, executed by Fritz Glarner, his photographer friend, juxtaposing their respective photos.

Excerpt

« Force Mauvaise / Evil force :

To slash, to cut to pieces, to slash everything smaller than me, the poorer, the less strong. Slash, slice, kill, scream and slaughter. Starve, defame, scream, kill, steal, incarcerate, execute, slowly deplete, leave only bones and skin. Choke, undermine, slander, crush with the boot, pierce the heart with laughter. Twisting, biting, beating, slaughtering, sneering, screaming, killing, looking like someone, being respected by all and admired, being loved on command. To give short orders: love me like this, like that! Enough of this! And again! Screaming, killing, splitting the soul, hanging, learning to spit, punishing, kneading, hating, smearing, screaming, killing, harming, cursing, destroying and disuniting, and never ceasing to slaughter.

Orgueil / Pride:

Enough! You go too fast, dear friend. You forget that we are brothers and that our rights are equal. You must leave at least a part of this rich country. You will not take everything: this booty is vast enough to be shared.

Force Mauvaise / Evil force:

To twist, to bite, to pull down.

Orgueil / Pride:

Think that if I were not with you, this country would surely escape you, for I am the one who recruits the bulk of your troops. Don’t think that you would have such a good time, with your few henchmen and your few traitors, if I left you for a while. What would you do against patience? Against non-resistance? What would you do against humility and simplicity? I believe, my dear, that you would be seriously handicapped, perhaps impotent, and condemned to immobility. For it is not only the allies that I bring to you that feed your strength, but also, as you know, the opposing violence. And how do you want it to emerge, this opposing violence, so precious to you, if I have not gone through this process to prepare the ground, to present my alcoholic drug under a wide variety of labels, to individuals and peoples? And what other than me would do it? What other than me gets well received everywhere, possessing an appointed seat in the inner fort of every man? …»

↑

Force mauvaise, Sept 20 septembre 1935, IX.

1934 – 1939

Anduze and the rise of Nazism

The Seuphors first settled for a few months in a little house near Nîmes, lent to them by Léon Marsal, a friend and furniture dealer. The announcement of a forthcoming birth led them to look for a house. They finally found it in Anduze, a Cevennes village that was then half empty. It was rather a ruin that they bought for the modest sum of 1500 francs and that they restored little by little.

In December 1934, Seuphor created a new magazine: La Nouvelle Campagne. Suzanne typed the 45 copies to which their friends subscribed. They published 30 issues from December 1934 to July 1939. Despite living far from Paris, the Seuphors maintained links and a regular correspondence with the artists and writers that Michel had met in Paris, in particular with the Arps, the Delaunays, Mondrian etc. Seuphor also collaborated regularly with local newspapers, as well as with the weekly magazine Sept published by the Dominican Fathers of Juvisy. The sale of his articles and subscriptions to La Nouvelle Campagne were the main source of income for the household until 1937.

Seuphor published there his reflections on social issues, his poems, as well as political articles in which he denounced, among others, Hitler and Mussolini, communism and fascism. One of his articles, entitled Force Mauvaise in reaction to the invasion of Ethiopia by Mussolini, appeared in Sept. 20, 1935. It is a fictitious dialogue between Hitler (alias Force Mauvaise /Evil force) and Mussolini (alias Orgueil / Pride) – at the time they had not yet met – in which he makes them discuss the fate of Europe. Seuphor chose to illustrate his article with a photomontage, executed by Fritz Glarner, his photographer friend, juxtaposing their respective photos.

Excerpt

« Force Mauvaise / Evil force :

To slash, to cut to pieces, to slash everything smaller than me, the poorer, the less strong. Slash, slice, kill, scream and slaughter. Starve, defame, scream, kill, steal, incarcerate, execute, slowly deplete, leave only bones and skin. Choke, undermine, slander, crush with the boot, pierce the heart with laughter. Twisting, biting, beating, slaughtering, sneering, screaming, killing, looking like someone, being respected by all and admired, being loved on command. To give short orders: love me like this, like that! Enough of this! And again! Screaming, killing, splitting the soul, hanging, learning to spit, punishing, kneading, hating, smearing, screaming, killing, harming, cursing, destroying and disuniting, and never ceasing to slaughter.

Orgueil / Pride:

Enough! You go too fast, dear friend. You forget that we are brothers and that our rights are equal. You must leave at least a part of this rich country. You will not take everything: this booty is vast enough to be shared.

Force Mauvaise / Evil force:

To twist, to bite, to pull down.

Orgueil / Pride:

Think that if I were not with you, this country would surely escape you, for I am the one who recruits the bulk of your troops. Don’t think that you would have such a good time, with your few henchmen and your few traitors, if I left you for a while. What would you do against patience? Against non-resistance? What would you do against humility and simplicity? I believe, my dear, that you would be seriously handicapped, perhaps impotent, and condemned to immobility. For it is not only the allies that I bring to you that feed your strength, but also, as you know, the opposing violence. And how do you want it to emerge, this opposing violence, so precious to you, if I have not gone through this process to prepare the ground, to present my alcoholic drug under a wide variety of labels, to individuals and peoples? And what other than me would do it? What other than me gets well received everywhere, possessing an appointed seat in the inner fort of every man? …»

↑

Force mauvaise, Sept 20 septembre 1935, IX.

In April 1935, the Corréa editions published Dans le royaume du cœur, a collection of poems written shortly before leaving Paris. Seuphor also published moral essays, such as Discours aux enfants, published by Emmanuel Vitte in Lyons in 1935, and L’ardente Paix, a collection of religiously inspired sonnets, which was published by the Brussels-based Cahiers du Journal des Poètes, in August 1936.

In June 1935, four months after his birth, their first child Clément died suddenly. It was a terrible blow for the young parents who took refuge in the Catholic faith and, for Michel, in literary creation. He published the poem Naissance et mort d’un enfant (Birth and Death of a Child) in Sept, which expresses this impossible grief. He also began to write his first novel, Histoires de grand dadais, He finished writing a year later in October 1936, and published it in 1938 with Ramgal, in Thuilles, Belgium. Their second son Régis was born in November 1936.

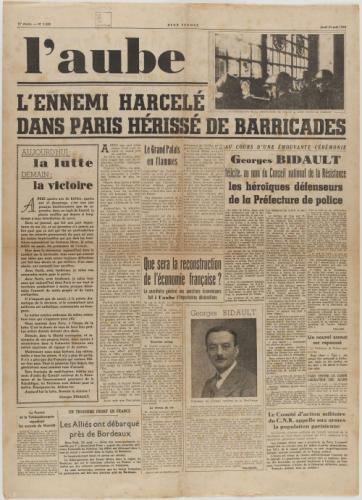

Seuphor published numerous articles in Sept, such as ‘Où va l’Europe?’ (Where is Europe Going?), which sounded the alarm about the rise of Nazism and Fascism; poems such as ‘La mascarade’, ‘Crux de Cruce’, and ‘Le jour mal éclairé’; and, in 1937, excerpts from Histoires de grand dadais. He also began to collaborate with the left-wing Catholic daily L’Aube. In 1937, he also published his first article on Mondrian in the Flemish magazine Opbouwen (Christen-calvinist, Opbouwen, X).

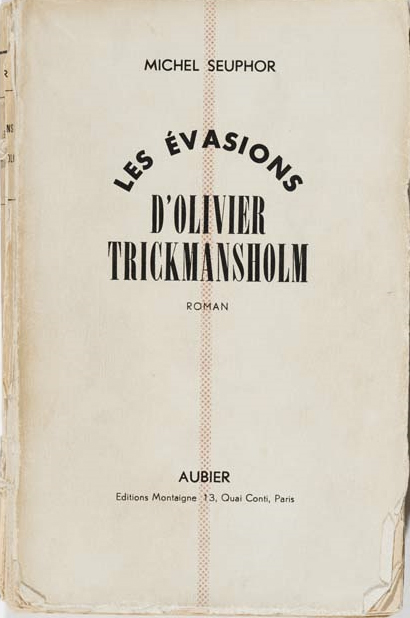

A psychological shock occurred in 1937, when the Vatican banned the publication of Sept on spurious grounds, in reality because the magazine’s anti-fascist positions disturbed the Vatican’s political relations with Mussolini. Seuphor lost his main income, and at the same time his faith and trust in the Catholic Church. A deep moral crisis followed, from which he recovered by writing a key novel about his artistic life in Paris in the 1920s, Les évasions d’Olivier Trickmansholm. (The Escapes of Olivier Trickmansholm).

« The blow I received, in my isolation of Anduze, almost cost me my reason. Everything was sinking with Sept, the whole Church was wrecked, became Machiavellian, practicing lies against its supreme authority and sanctity. What was left? The Church was in ruins. At the same time, the meager income I received from Paris as a reward for my articles was falling from my hands. I was a castaway on a deserted life. My disarray was such that, for several days, I could not speak to my wife. I could hardly touch the food she brought me on a tray in the bedroom, which I never left. Then, suddenly, the love of writing saved me. The word ‘escape’ seemed to be the key to my past existence. I had found a theme to tell a life story, my own, and it was Les évasions d’Olivier Trickmansholm, a voluminous novel that kept my mind busy throughout the following winter, and it exorcised me. » (Le jeu de je, 1976)

Seuphor also translated his revolt at Europe’s political situation by writing a series of politico-religious dialogues that he published first in La Nouvelle Campagne, a voluminous novel that kept my mind busy throughout the following winter, and it exorcised me.” (Le jeu de je, 1976)

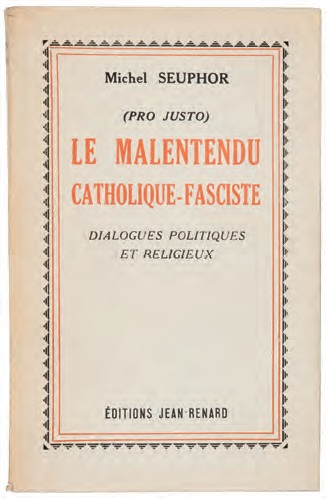

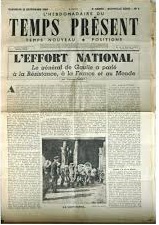

Seuphor also translated his revolt at Europe’s political situation by writing a series of politico-religious dialogues that he published first in La Nouvelle Campagne, and then, in 1939, in the Jean Renard editions in Paris, under the title, (imposed by the editor Jean-Renard because more provocative), Le malentendu Catholique-Fasciste (The Catholic-fascist misunderstanding). His positions also led to a break with the philosopher Gustave Thibon, who lived in Saint-Marcel-d’Ardèche and with whom he had begun a friendship (Thibon supported the Vichy regime). Seuphor continued to publish political articles such as ‘Sommes-nous encore libres?’ in L’Aube and ‘Savoir dire: Halte!’ in a new magazine, Temps Présent, which replaced Sept, but was directed by lay people, notably Stanislas Fumet.

In October 1938, the Seuphors went to Paris where they stayed for two months, interspersed with a stay in Antwerp to introduce their son to his paternal grandmother.

During this stay in Paris, Seuphor assiduously frequented Jean Paulhan and the circles of the Nouvelle Revue Française, who were interested in his writings. However, he could not obtain complete freedom to write, and therefore decided not to pursue this collaboration. Eventually, it was Fernand Aubier, director of Editions Montaigne who, in 1939, decided to publish Les évasions d’Olivier Trickmansholm, which came out one month before the war declaration. In the meantime, Aubier did everything possible to ensure that the book would win the Goncourt Prize and called Seuphor to Paris to attend a luncheon offered to several members of the Academy. The deal seemed to be closed, but the war declaration led to the cancellation of the Goncourt that year, and Aubier gave up. Seuphor concludes in Le jeu de je: “I was saved from fortune, from fame, from a certain guardianship, and from banality. »

In April 1935, the Corréa editions published Dans le royaume du cœur, a collection of poems written shortly before leaving Paris. Seuphor also published moral essays, such as Discours aux enfants, published by Emmanuel Vitte in Lyons in 1935, and L’ardente Paix, a collection of religiously inspired sonnets, which was published by the Brussels-based Cahiers du Journal des Poètes, in August 1936.

In June 1935, four months after his birth, their first child Clément died suddenly. It was a terrible blow for the young parents who took refuge in the Catholic faith and, for Michel, in literary creation. He published the poem Naissance et mort d’un enfant (Birth and Death of a Child) in Sept, which expresses this impossible grief. He also began to write his first novel, Histoires de grand dadais, He finished writing a year later in October 1936, and published it in 1938 with Ramgal, in Thuilles, Belgium. Their second son Régis was born in November 1936.

Seuphor published numerous articles in Sept, such as ‘Où va l’Europe?’ (Where is Europe Going?), which sounded the alarm about the rise of Nazism and Fascism; poems such as ‘La mascarade’, ‘Crux de Cruce’, and ‘Le jour mal éclairé’; and, in 1937, excerpts from Histoires de grand dadais. He also began to collaborate with the left-wing Catholic daily L’Aube. In 1937, he also published his first article on Mondrian in the Flemish magazine Opbouwen (Christen-calvinist, Opbouwen, X).

A psychological shock occurred in 1937, when the Vatican banned the publication of Sept on spurious grounds, in reality because the magazine’s anti-fascist positions disturbed the Vatican’s political relations with Mussolini. Seuphor lost his main income, and at the same time his faith and trust in the Catholic Church. A deep moral crisis followed, from which he recovered by writing a key novel about his artistic life in Paris in the 1920s, Les évasions d’Olivier Trickmansholm. (The Escapes of Olivier Trickmansholm).

« The blow I received, in my isolation of Anduze, almost cost me my reason. Everything was sinking with Sept, the whole Church was wrecked, became Machiavellian, practicing lies against its supreme authority and sanctity. What was left? The Church was in ruins. At the same time, the meager income I received from Paris as a reward for my articles was falling from my hands. I was a castaway on a deserted life. My disarray was such that, for several days, I could not speak to my wife. I could hardly touch the food she brought me on a tray in the bedroom, which I never left. Then, suddenly, the love of writing saved me. The word ‘escape’ seemed to be the key to my past existence. I had found a theme to tell a life story, my own, and it was Les évasions d’Olivier Trickmansholm, a voluminous novel that kept my mind busy throughout the following winter, and it exorcised me. » (Le jeu de je, 1976)

Seuphor also translated his revolt at Europe’s political situation by writing a series of politico-religious dialogues that he published first in La Nouvelle Campagne, a voluminous novel that kept my mind busy throughout the following winter, and it exorcised me.” (Le jeu de je, 1976)

Seuphor also translated his revolt at Europe’s political situation by writing a series of politico-religious dialogues that he published first in La Nouvelle Campagne, and then, in 1939, in the Jean Renard editions in Paris, under the title, (imposed by the editor Jean-Renard because more provocative), Le malentendu Catholique-Fasciste (The Catholic-fascist misunderstanding). His positions also led to a break with the philosopher Gustave Thibon, who lived in Saint-Marcel-d’Ardèche and with whom he had begun a friendship (Thibon supported the Vichy regime). Seuphor continued to publish political articles such as ‘Sommes-nous encore libres?’ in L’Aube and ‘Savoir dire: Halte!’ in a new magazine, Temps Présent, which replaced Sept, but was directed by lay people, notably Stanislas Fumet.

In October 1938, the Seuphors went to Paris where they stayed for two months, interspersed with a stay in Antwerp to introduce their son to his paternal grandmother.

During this stay in Paris, Seuphor assiduously frequented Jean Paulhan and the circles of the Nouvelle Revue Française, who were interested in his writings. However, he could not obtain complete freedom to write, and therefore decided not to pursue this collaboration. Eventually, it was Fernand Aubier, director of Editions Montaigne who, in 1939, decided to publish Les évasions d’Olivier Trickmansholm, which came out one month before the war declaration. In the meantime, Aubier did everything possible to ensure that the book would win the Goncourt Prize and called Seuphor to Paris to attend a luncheon offered to several members of the Academy. The deal seemed to be closed, but the war declaration led to the cancellation of the Goncourt that year, and Aubier gave up. Seuphor concludes in Le jeu de je: “I was saved from fortune, from fame, from a certain guardianship, and from banality. »

Texts by Seuphor published during this period (1934-1939)

1934

- Style ; Nova et Vetera

- Oui …, mais ; Esprit

- Contrastes parisiens, Hubert Robert et les Abstraits ; La vie intellectuelle, 1UI.

- Fumet, Martin de Porres (Chronique des livres) ; Nova et Vetera

- L’épée chrétienne ; Sept 1,

1935

- Anduze au pays cévenol ; L’Echo d’Anduze,

- Force mauvaise ; Sept 20,

- Le jazz hot ; La vie intellectuelle, III.

- Anduze terre de paix ; L’Echo d’Anduze, IX; Sept, 19.VII.

- Italie 1909-1935 ; Sept, 1X.

- Sur l’aviation française au Petit Palais ; La Meuse (Liège), VI.

- Bleu, Si tu savais, Souvent (poèmes) ; Sept, VII.

- Matt Talbot, Saint Thomas et un “chemin de la croix” (Chronique des livres) ; Le Courrier de Genève

- Clarté de Noel (poème) ; Sept, XII

- Remerciements pour l’an 1934 (poème) ; Sept,

- Naissance d’un enfant mâle ; Sept, III.

- Faire Oraison, Présence, Le pain et le vin (poèmes) ; Sept, VIII.

- Nuit sur nous (poème) ; Sept 5, 17.VII

1936

- Le sport et l’art ; Sept, 7. II.

- Une technique de l’éducation (la méthode Montessori) ; Sept, V.

- L’extraordinaire destinée d’un peintre : Domenico Theotocopuli ; L’art sacré

- Fraicheur de l’église ; Orientations, X.

- Le juste milieu et la juste mesure ; Orientations, XI.

- Réponse à l’enquête : le poète et son temps doit-il être de son temps ? Et comment doit-il l’être ? ; Cahiers de journal de poètes 16

- Où va l’Europe ? ; Sept, 1VI.

- La terre de Paix ; Sept, I.

- Theresa Higginson ; Sept, 11.

- Deux petits poèmes ; Sept 107, III.

- Crux de Cruce, La mascarade (poèmes) ; Sept VIII.

- Le musée du désert et la région anduzienne ; La Dépêche de Toulouse, VIII.

- Tout était Ià ; Christus, XII.

- Nous fêtons Pierre-Louis Flouquet ; Courrier des poètes 3, XII.

1937

- Notes parisiennes ; Orientations, III.

- Paradoxe sur les internationales ; L’Aube, 8. IV.

- La politesse ; L’Aube, VI.

- La justice ; L’Aube, VII.

- Vivre ; L’Aube, VII.

- L’Orgueil ; L’Aube, VII.

- Un rajeunissement de l’Ecriture ; La cité chrétienne, V.

- Mystique errante ; La Sève, X,

- La question des Loisirs ouvriers ; Christus, III,

- Vondel, Méditation d’un ermite en temps de carême ; La Sève 2

- Poèmes ; Christus,

- Est-ce possible ; L’Echo d’Anduze, III

- Victor Delhez, xylographe ; Le XXe siècle, III.

- Encore les ruines ; L’Echo d’Anduze,

- Fraicheur de l’église ; La vie catholique, 24. IV.

- Réponse à quelques lettres ; L’Aube, V.

- La Haine ; L’Aube, 21. Vll.

- Vendanges ; Christus,

- Gratuite (poème) ; Le XXe siècle, VIII.

- L’Amour de Ia patrie ; L’Aube, IX., 4. IX.

- Paradoxe sur les internationales », l’Aube, 8, IV, 1937.

- L’amitié ; Le patriote illustré, 1 IX.

- La poésie à son comble ; Orientations, VII, VIII.

- Fraicheur de L’été ; Le patriote illustré, VII.,

- Christen-calvinist ; Opbouwen,

- La veillée de novembre ; Temps présent, XII.

1938

- Sommes-nous encore libres ? ; L’Aube, IX.

- Construisons ; Temps présent, 11.

- Réponse à l’enquête : l’Inspiration poétique et la métrique ; Cahiers du journal des poètes, I

- Hölderlin (poèmes) ; Nova et Vetera

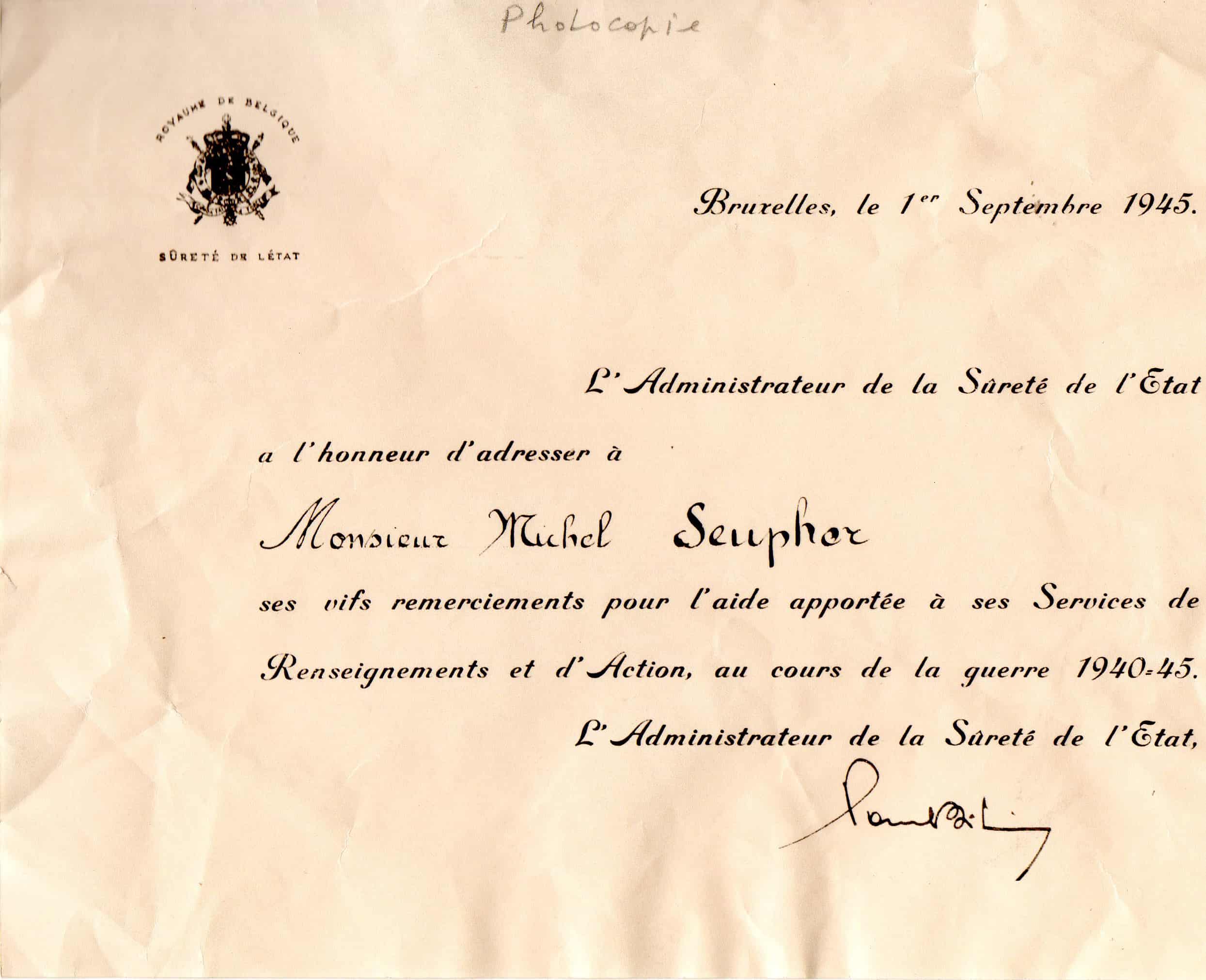

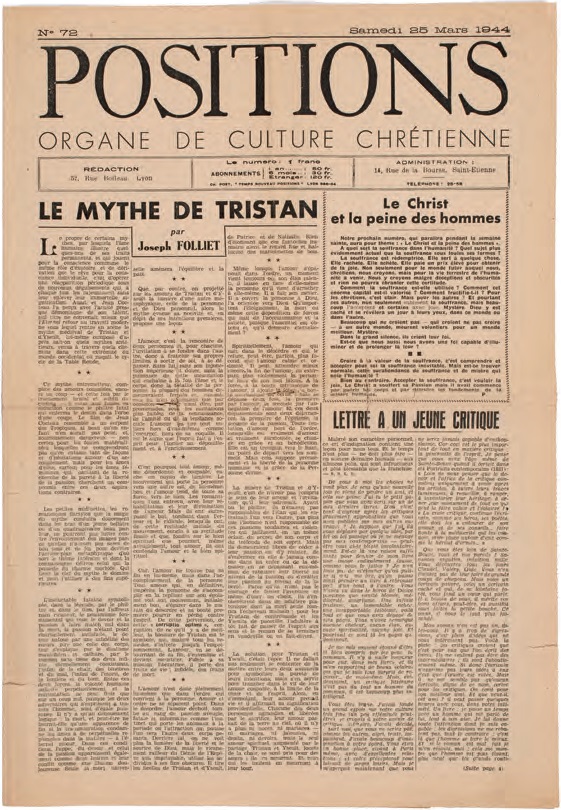

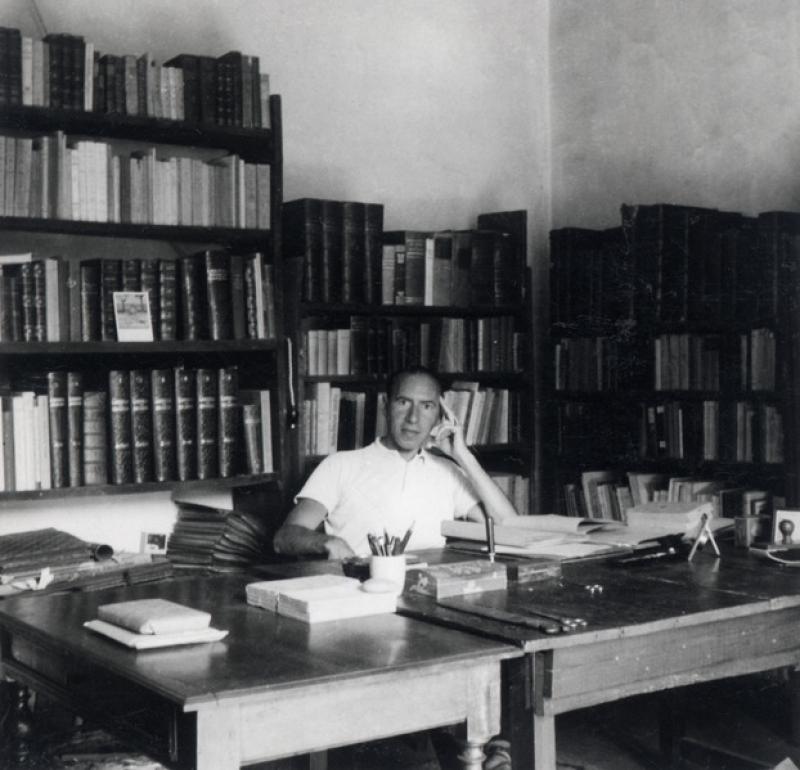

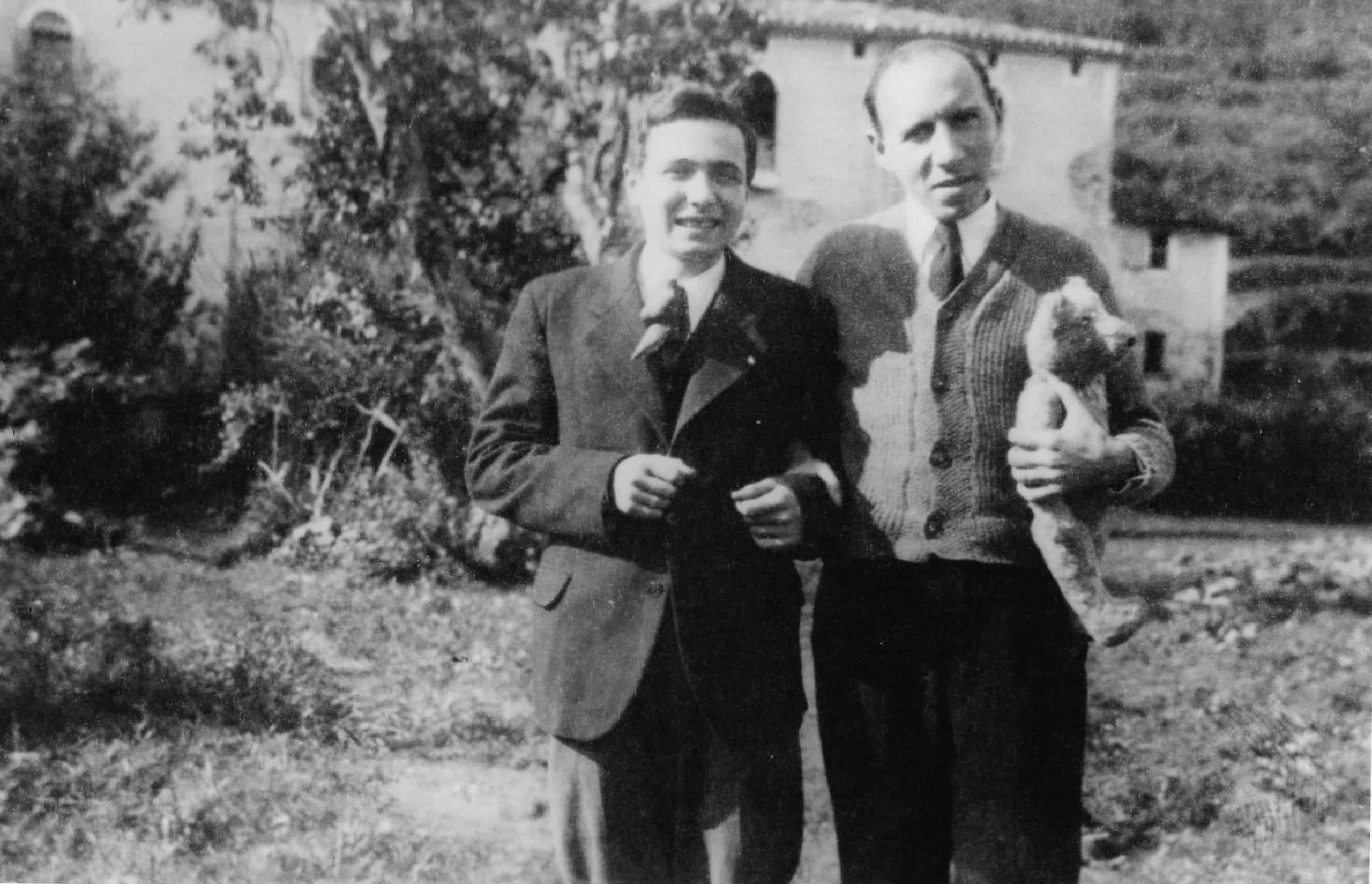

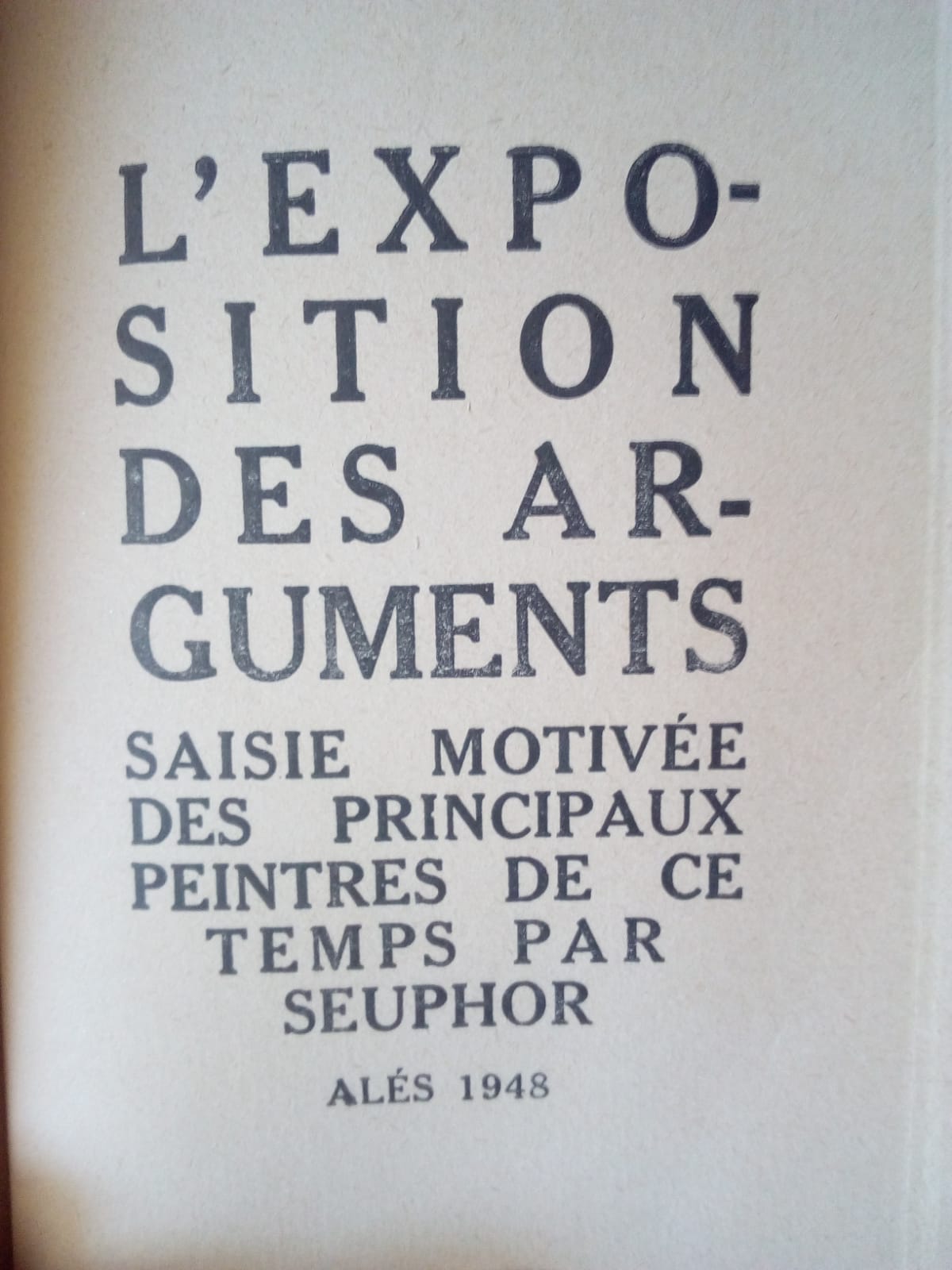

- Savoir dire : Halte ! ; Temps présent, IX.