MAGAZINES

MAGAZINES

« Why have I been doing reviews all my life or almost all my life? Because I believe in one essential thing: you must never be subordinate, you must never work for others. You must not give your freedom or your work capacity to others. When you have something to do or to say, you must give this capacity to yourself and not to those who could use it through their eyes or their filter. So, you have to create the place where you can express yourself, and this is the role of magazines. Moreover, this type of work can in no way be subordinated to its future. Take the single issue of the Documents internationaux de l’esprit nouveau. If we, Prampolini, Paul Dermée and myself, had subordinated the magazine to the probable readers of the time, three quarters of the texts would never have seen the light of day. There were only very new things, very sharp, and if these ideas seem natural today, it was not the case in 1927… so we should not have published them? Wait for the time when the public was in tune with us? At that time, no magazine would have printed Marinetti’s text on criticism, nor those of Schwitters or Mondrian… nor, for that matter, the texts of Het Overzicht, nor those of Cercle et carré in 1930. This is the ‘mission’ of an avant-garde magazine.»

↑

Excerpt from

Michel Seuphor, Un siècle de libertés.

Entretiens avec Alexandre Grenier, Hazan editions.

« Why have I been doing reviews all my life or almost all my life? Because I believe in one essential thing: you must never be subordinate, you must never work for others. You must not give your freedom or your work capacity to others. When you have something to do or to say, you must give this capacity to yourself and not to those who could use it through their eyes or their filter. So, you have to create the place where you can express yourself, and this is the role of magazines. Moreover, this type of work can in no way be subordinated to its future. Take the single issue of the Documents internationaux de l’esprit nouveau. If we, Prampolini, Paul Dermée and myself, had subordinated the magazine to the probable readers of the time, three quarters of the texts would never have seen the light of day. There were only very new things, very sharp, and if these ideas seem natural today, it was not the case in 1927… so we should not have published them? Wait for the time when the public was in tune with us? At that time, no magazine would have printed Marinetti’s text on criticism, nor those of Schwitters or Mondrian… nor, for that matter, the texts of Het Overzicht, nor those of Cercle et carré in 1930. This is the ‘mission’ of an avant-garde magazine.»

↑

Excerpt from

Michel Seuphor, Un siècle de libertés.

Entretiens avec Alexandre Grenier, Hazan editions.

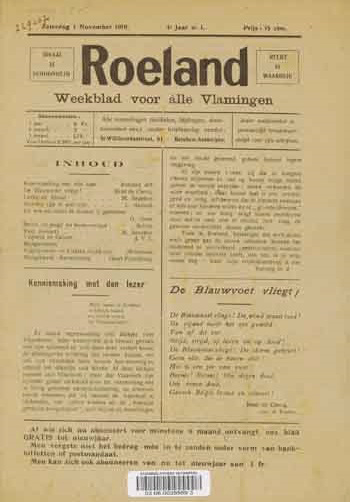

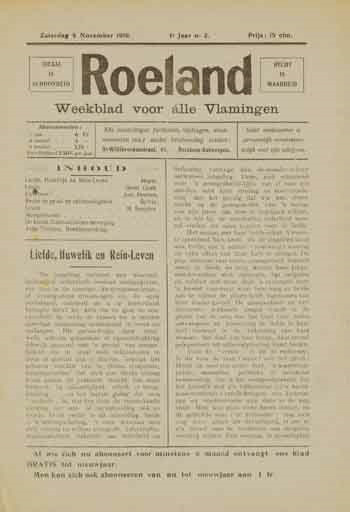

DE KLAUWAERT & ROELAND

In 1919, Michel Seuphor founded two Fleming magazines. The first one, De Klauwaert, had five issues and Roeland had two.

« As soon as I left school, I created a small Fleming magazine called De Klauwaert (« The man with the claw» ), a small sheet of blue paper, which I wrote almost alone and which I had printed at my own expense. It was a Fleming war cry. I was selling it to my former classmates, at the end of classes. The first issue appeared in January 1919, when I was not yet 18 years old. So my first job was as an amateur journalist.

I did four issues and it was so successful that a group of alumni from several schools in the city came to me and said, « You can’t do this alone. It has to go through our hands. We’ll give it more circulation, but we’ll continue as you started.» So they took away my little magazine, which they called Storm, with a subtitle like « Weekly of the Fleming Youth» . Storm still existed a few months before the declaration of war in 1939.»

↑

Michel Seuphor,

Une vie à angle droit

1988

Later, in the same year, together with his friend Jules van Beek, he founded Roeland, in the same format as De Klauwaert, but on gray paper this time. It is in Roeland that he published his first poems, powerfully driven by a need for discovery and independence.

DE KLAUWAERT & ROELAND

In 1919, Michel Seuphor founded two Fleming magazines. The first one, De Klauwaert, had five issues and Roeland had two.

« As soon as I left school, I created a small Fleming magazine called De Klauwaert (« The man with the claw» ), a small sheet of blue paper, which I wrote almost alone and which I had printed at my own expense. It was a Fleming war cry. I was selling it to my former classmates, at the end of classes. The first issue appeared in January 1919, when I was not yet 18 years old. So my first job was as an amateur journalist.

I did four issues and it was so successful that a group of alumni from several schools in the city came to me and said, « You can’t do this alone. It has to go through our hands. We’ll give it more circulation, but we’ll continue as you started.» So they took away my little magazine, which they called Storm, with a subtitle like « Weekly of the Fleming Youth» . Storm still existed a few months before the declaration of war in 1939.»

↑

Michel Seuphor,

Une vie à angle droit

1988

Later, in the same year, together with his friend Jules van Beek, he founded Roeland, in the same format as De Klauwaert, but on gray paper this time. It is in Roeland that he published his first poems, powerfully driven by a need for discovery and independence.

↑

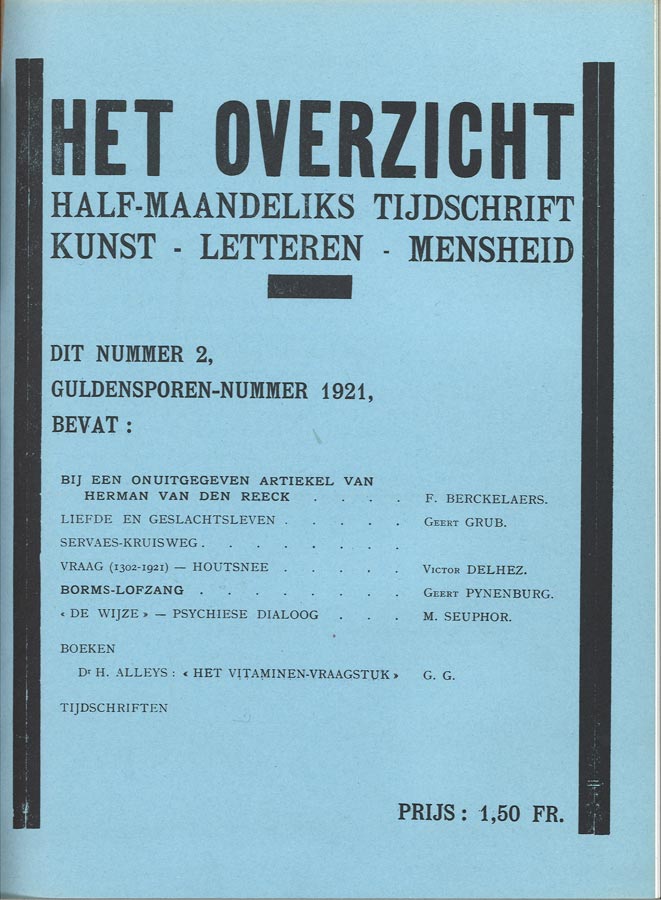

Het Overzicht

n° 1, 15 juin 1921

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 2, 1921

↑

Het Overzicht

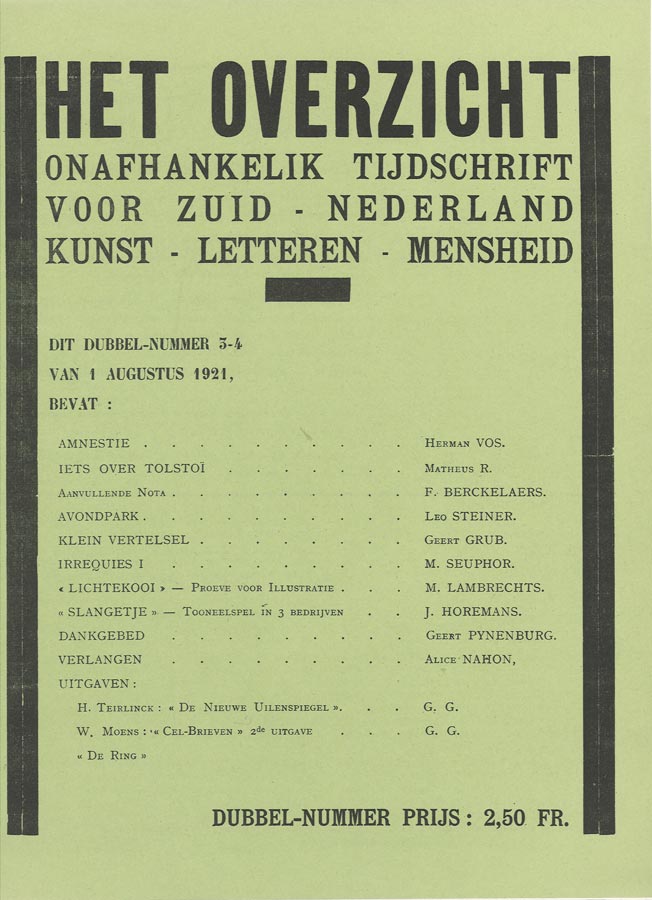

n° 3-4, Août 1921

↑

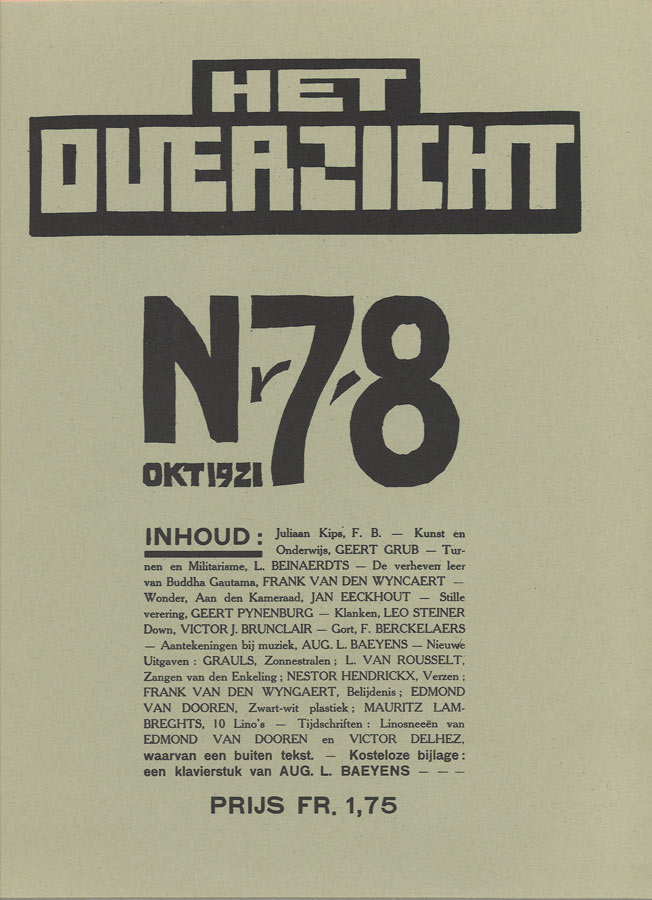

Het Overzicht

n° 7-8, Octobre 1921

↑

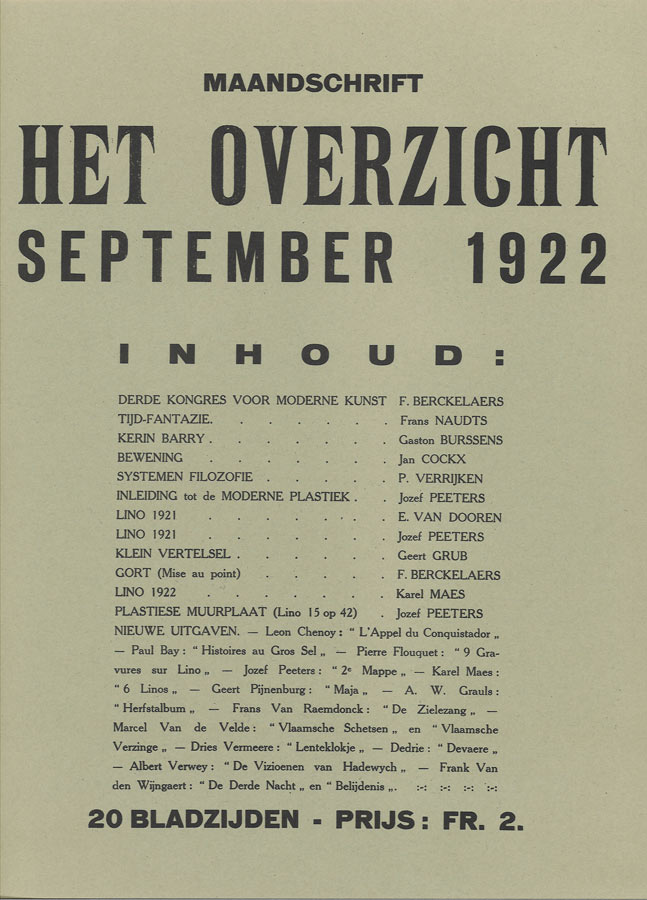

Het Overzicht

n° 12, Septembre 1922

↑

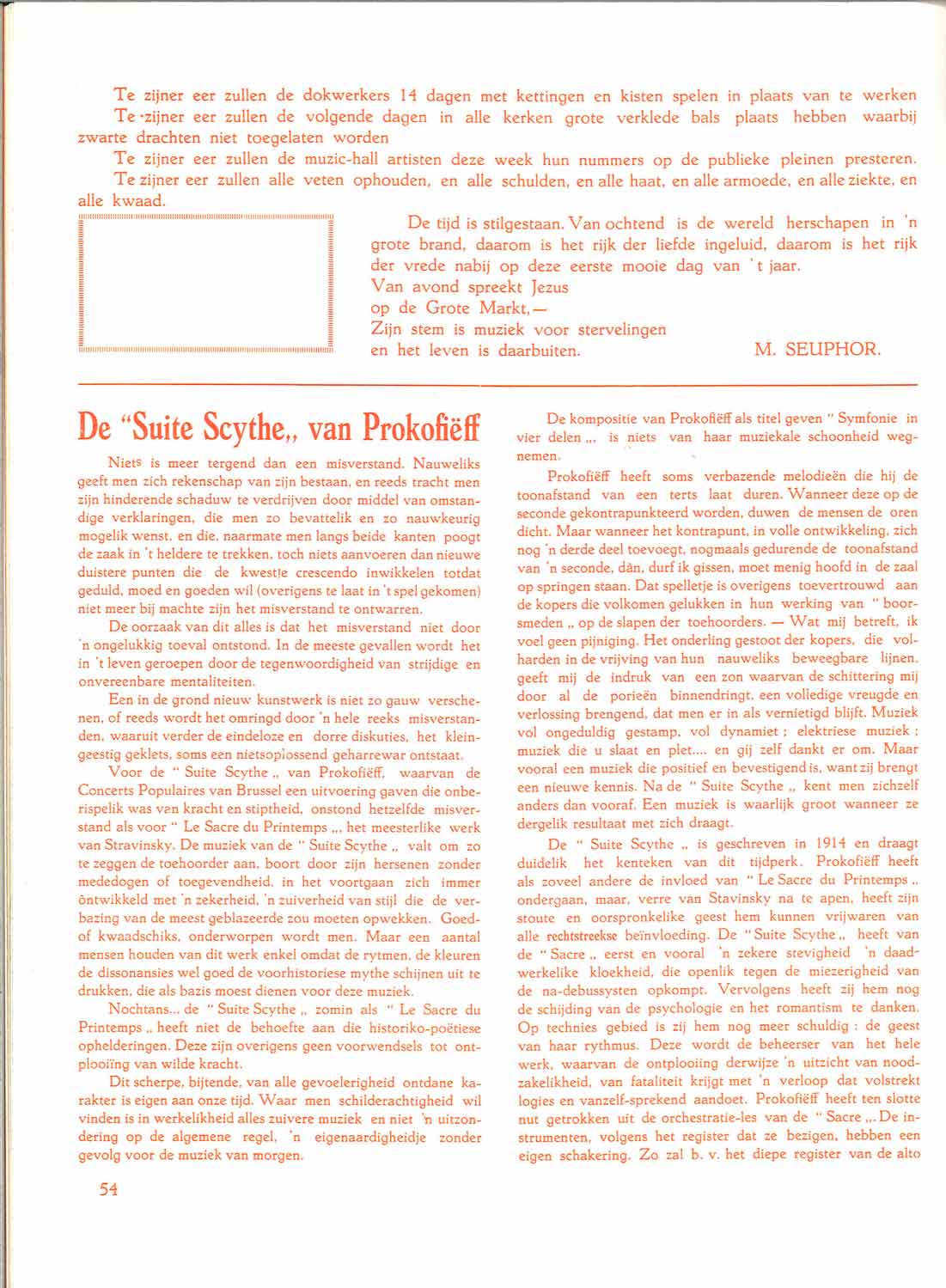

Het Overzicht

n° 14, Décembre 1922

Couverture J. Peeters

↑

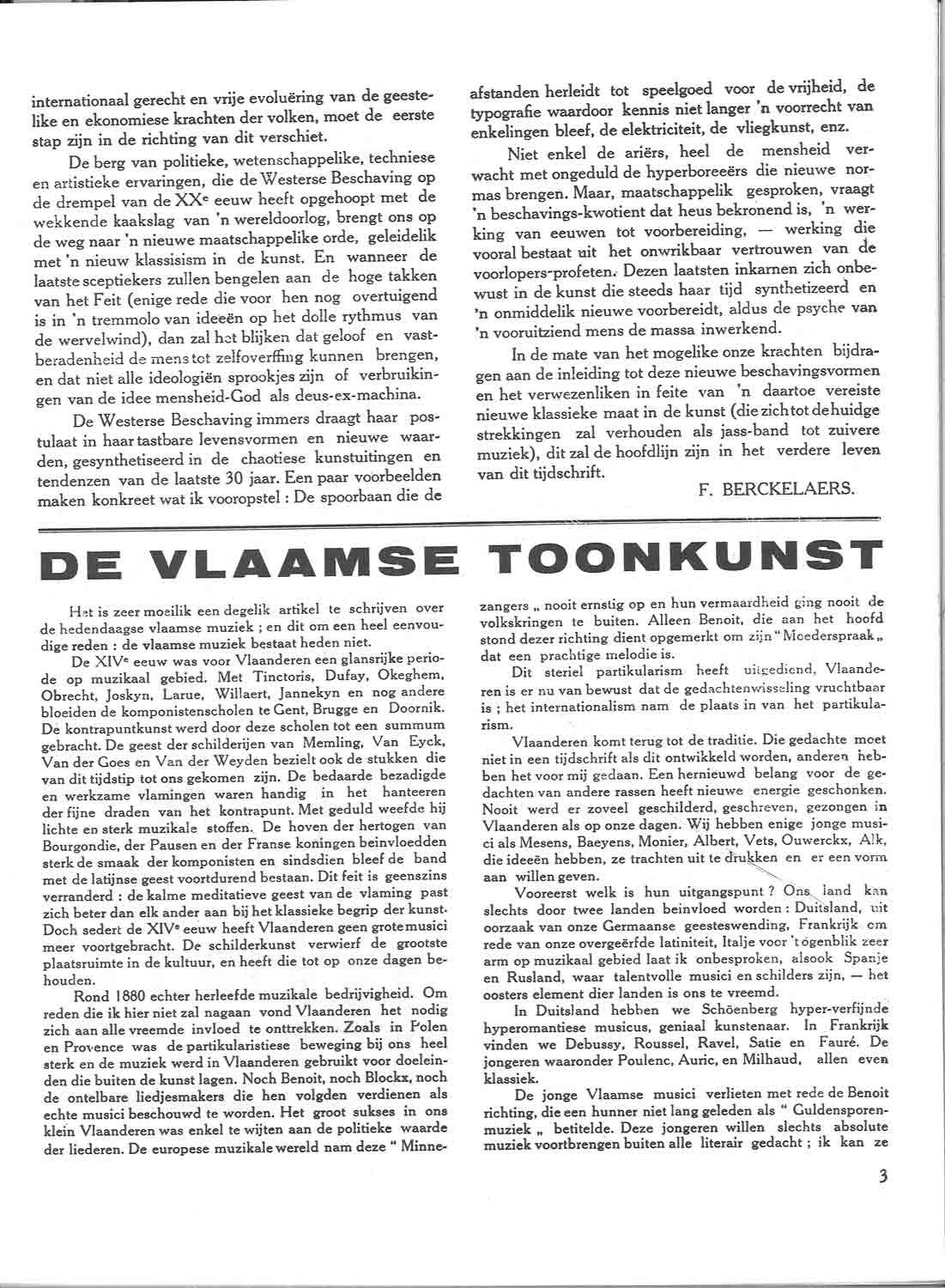

Het Overzicht

n° 15, Mars-Avril 1923

Couverture Servranckx

↑

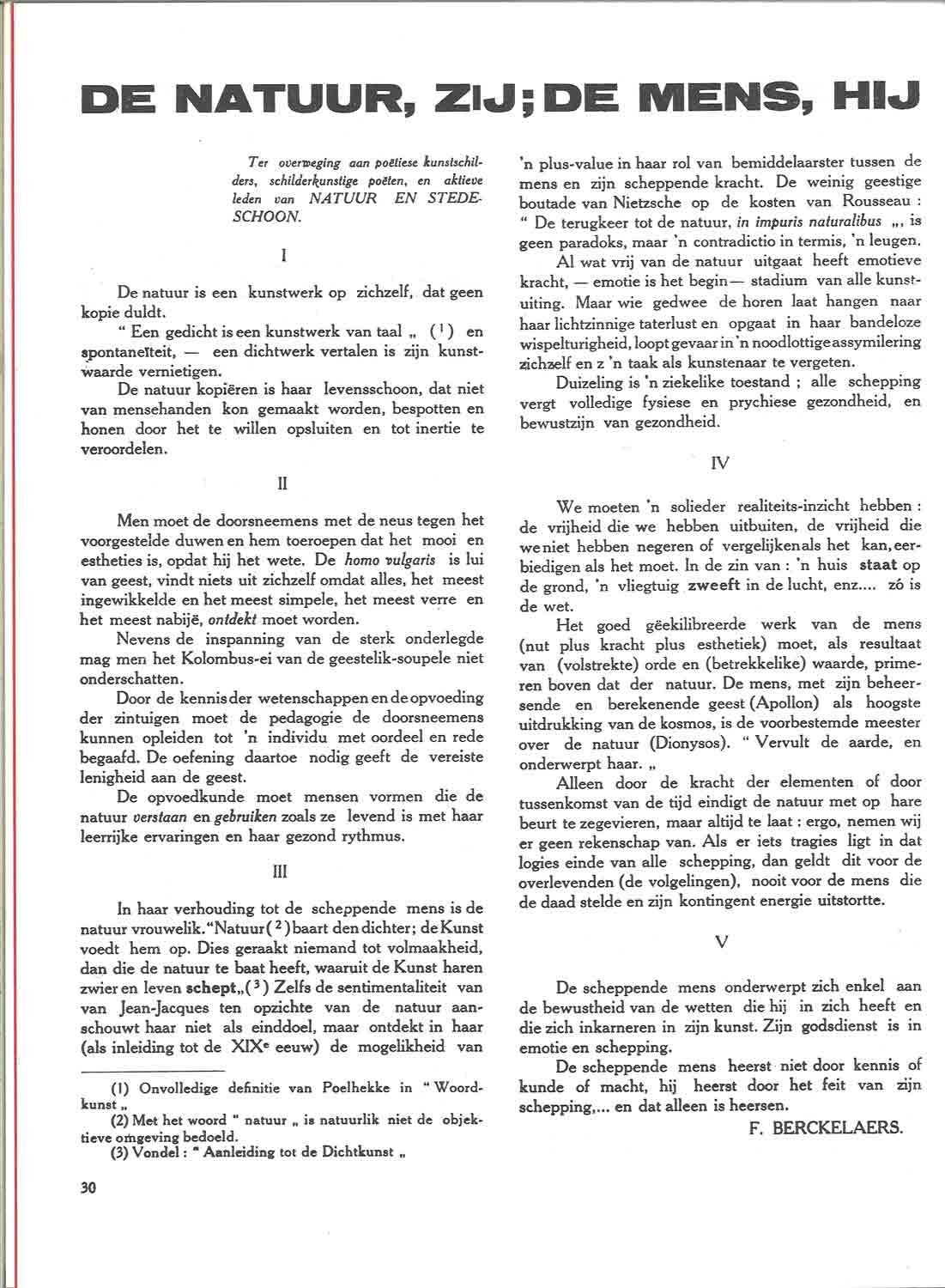

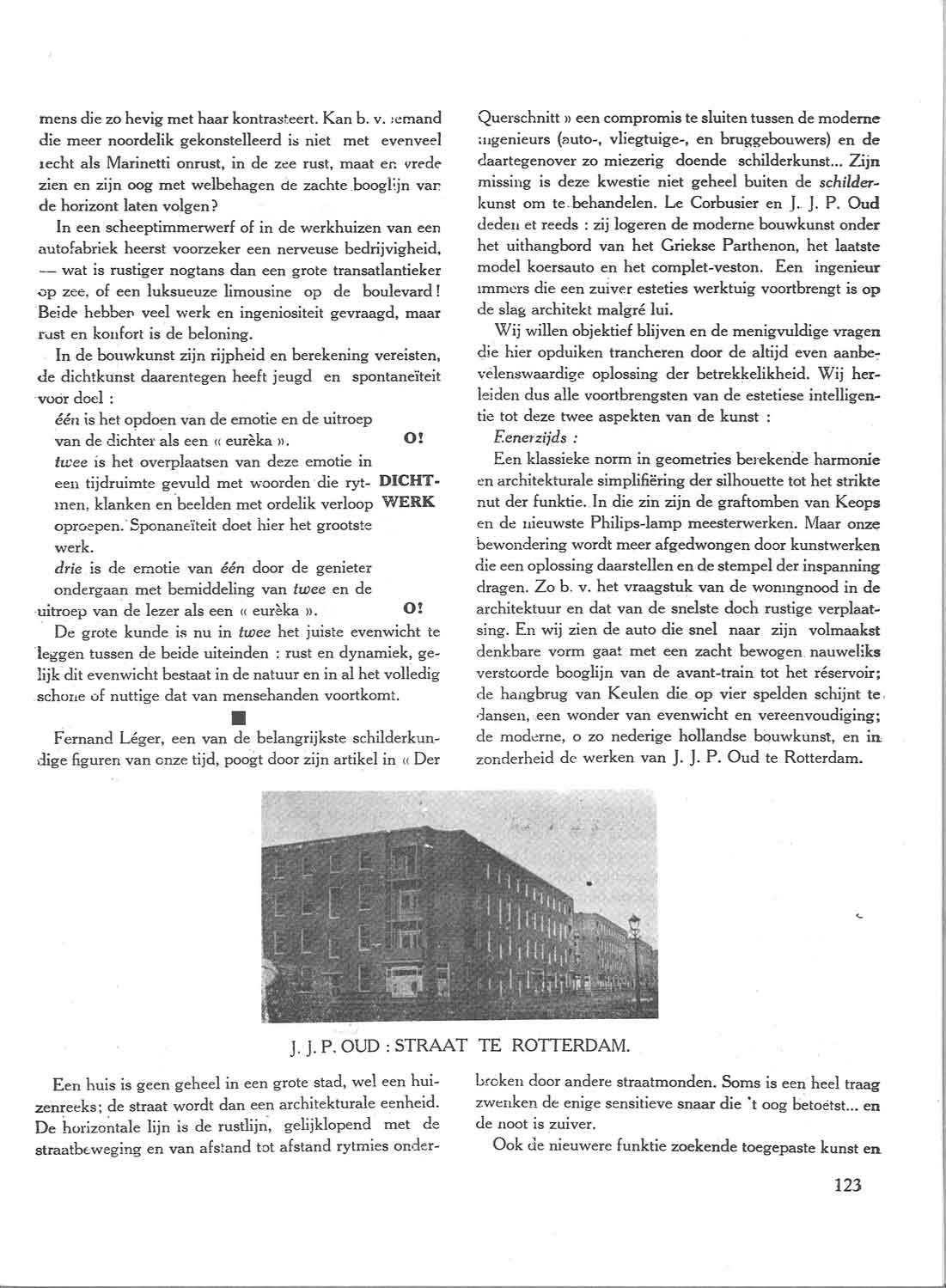

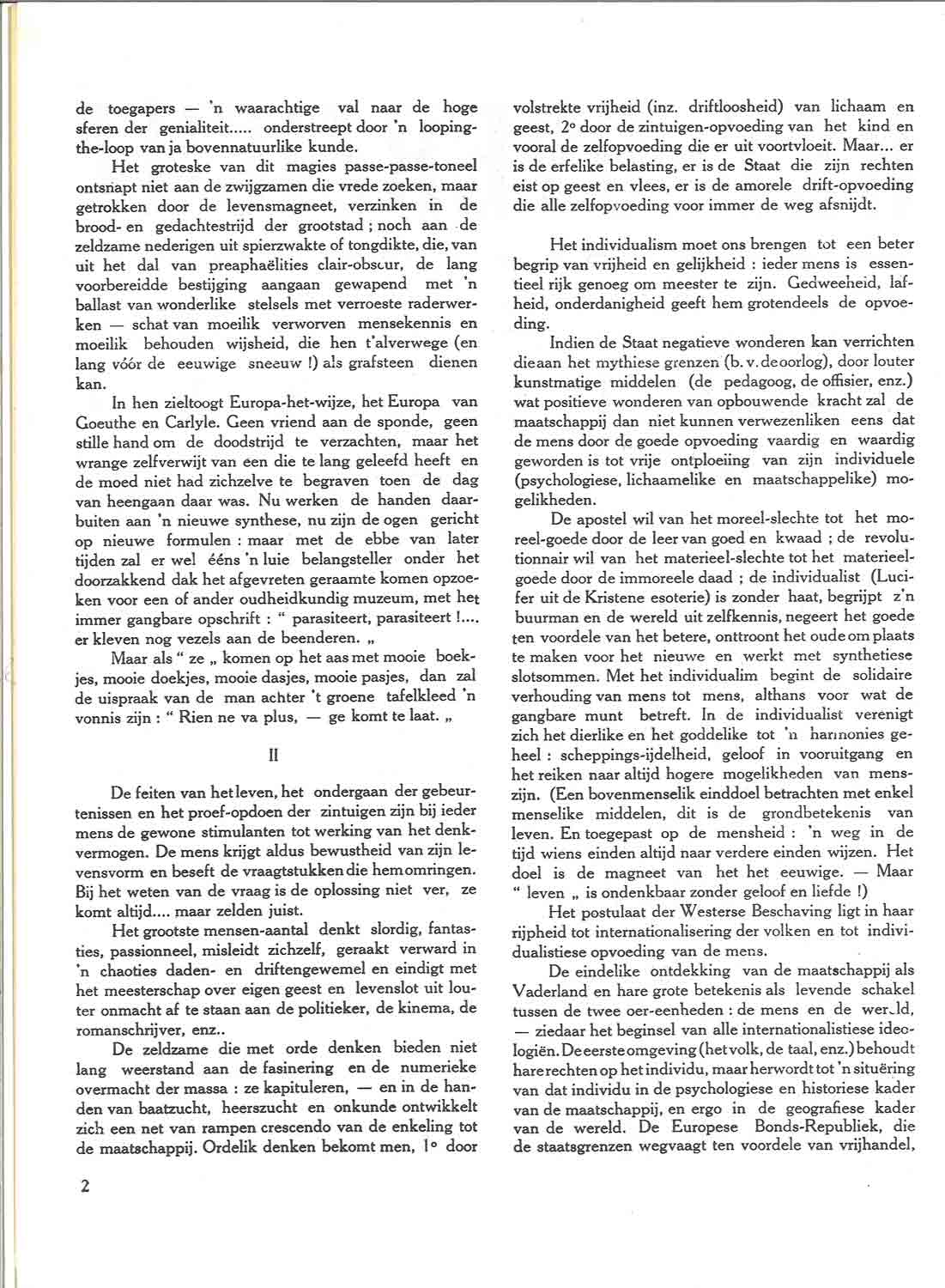

Het Overzicht, n° 15, Mars-Avril 1923

De natuur, Zij, De mens, Hij

F. Berckelaers

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 17, 1923

Couverture de Delaunay

↑

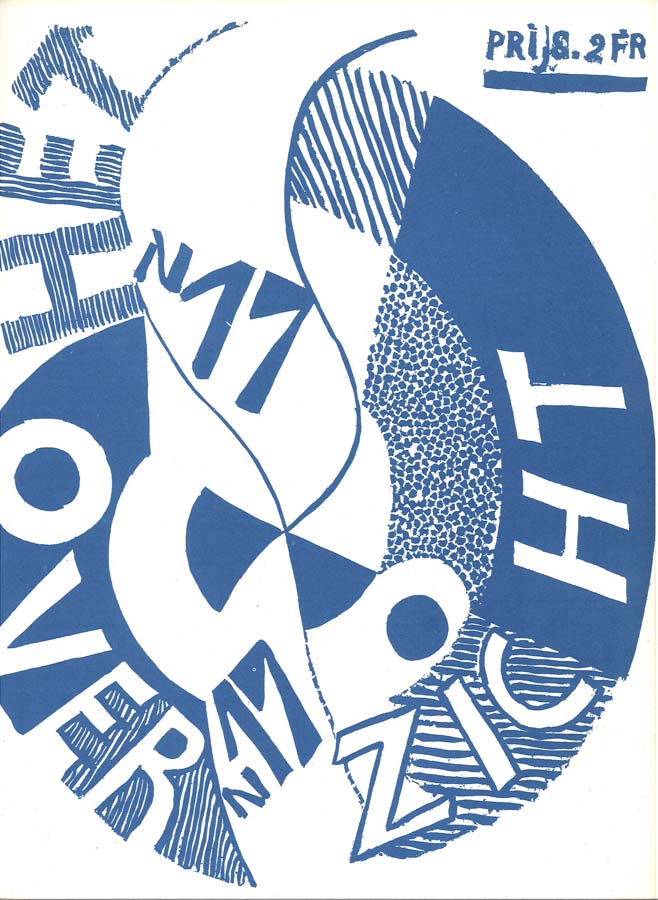

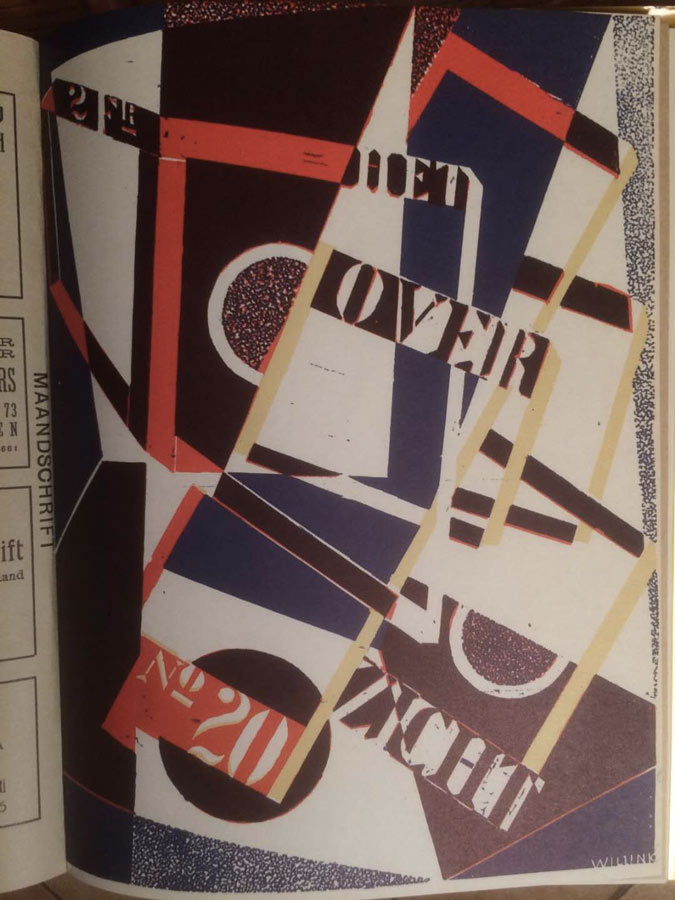

Het Overzicht

n° 20

Couverture Willinks

↑

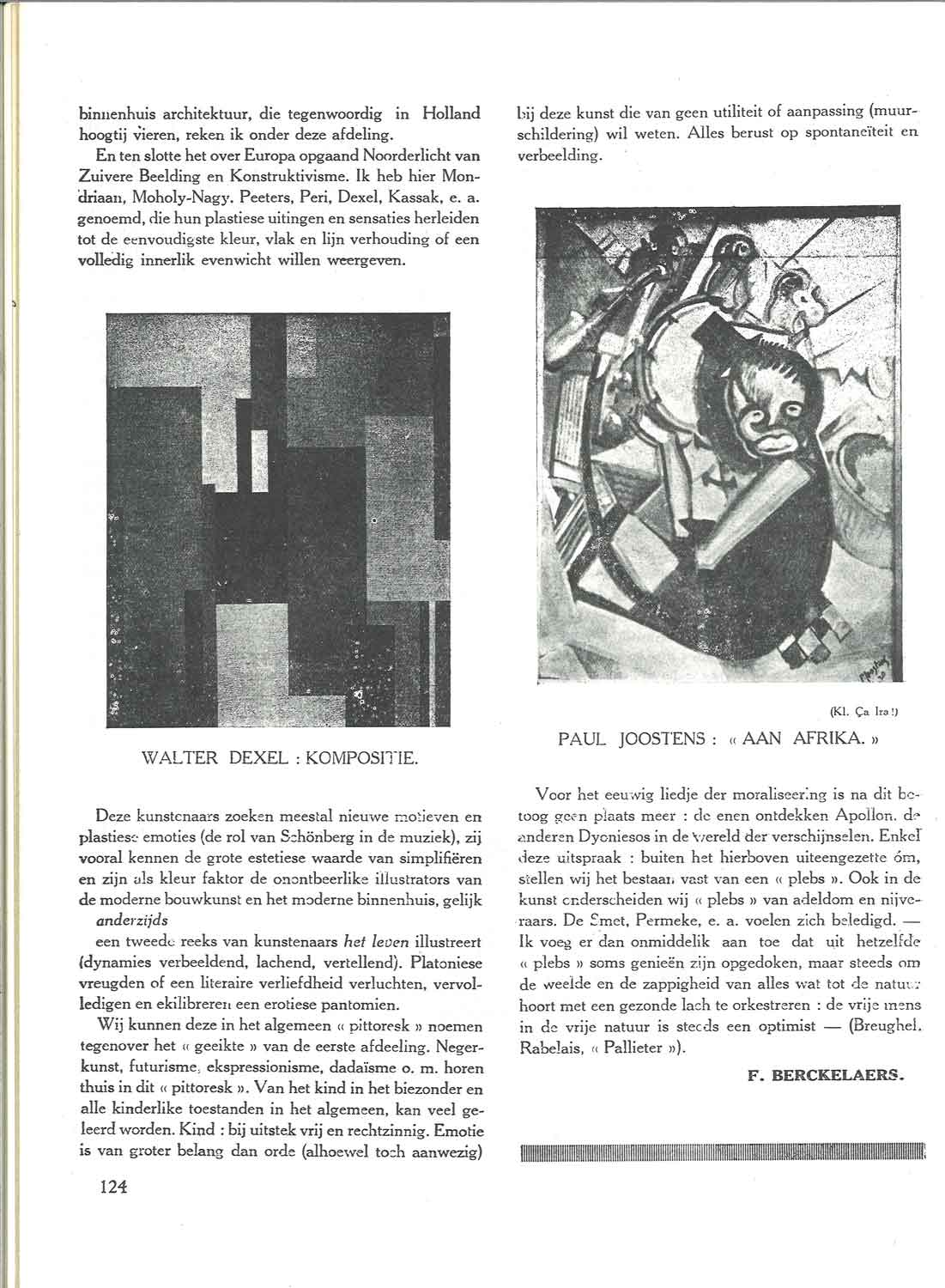

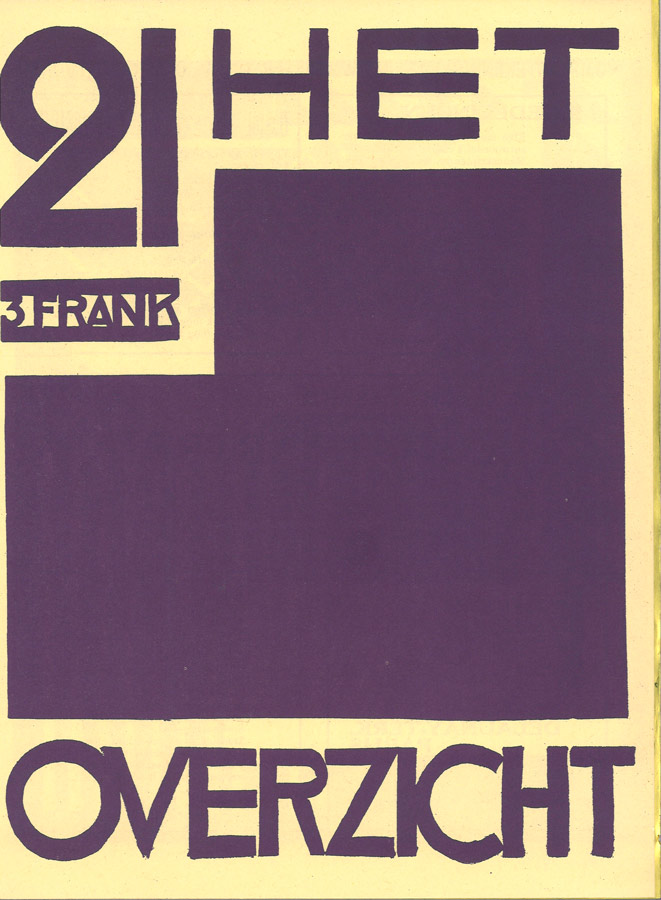

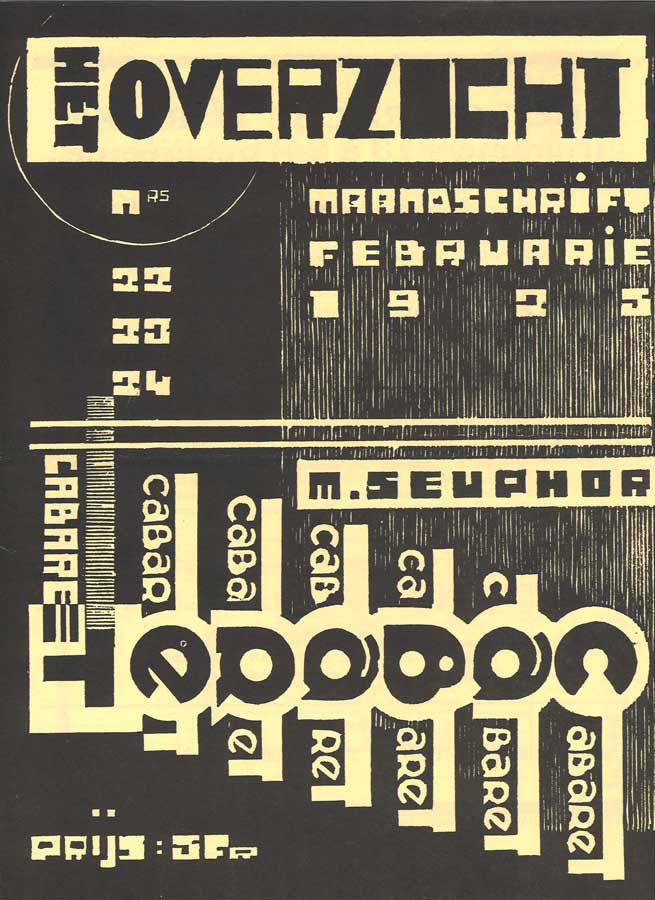

Het Overzicht

n° 22-23-24

Cabaret, Février 1925

Couverture J. Peeters

↑

Het Overzicht

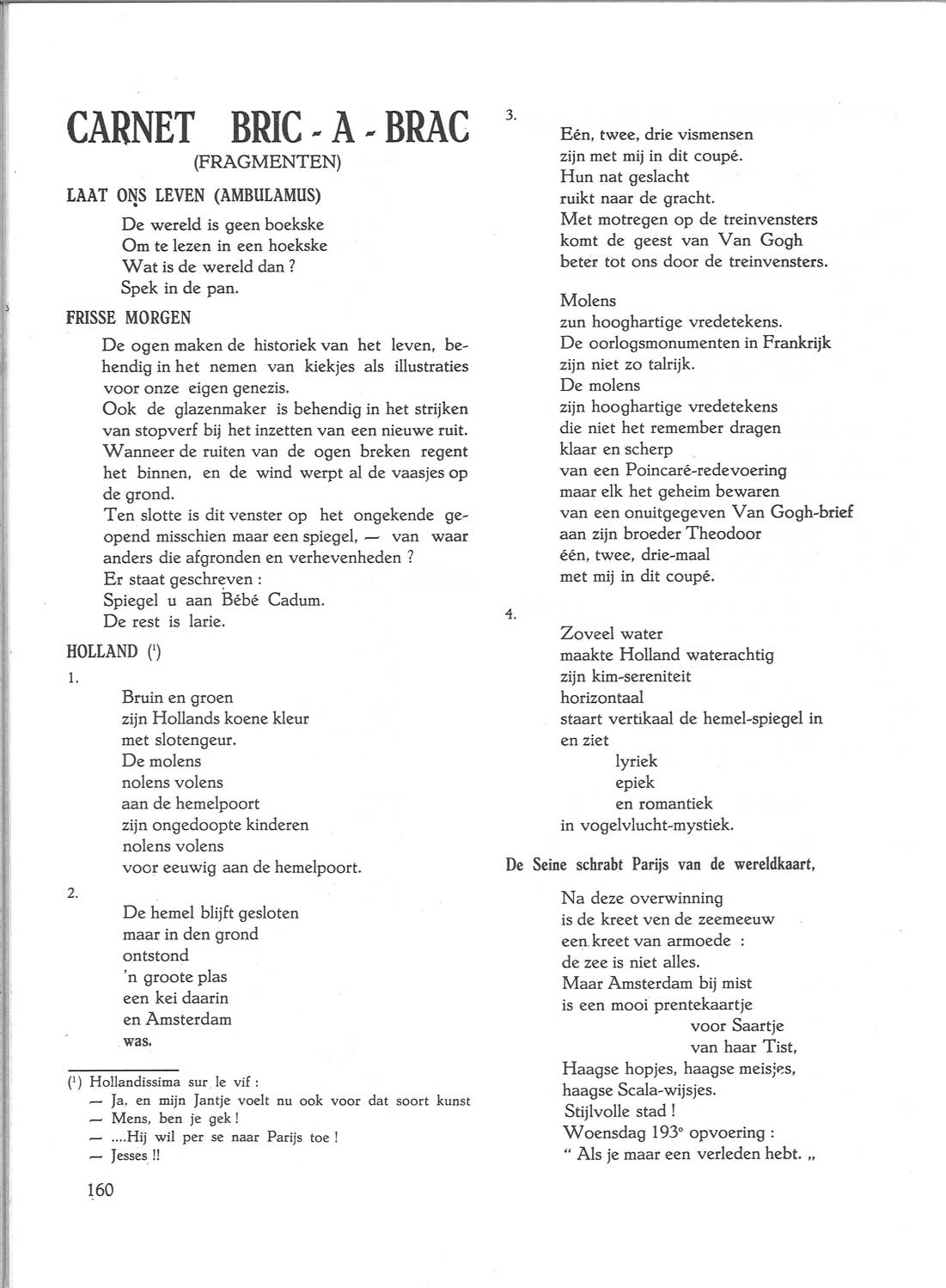

Carnet de Bric à Brac, n° 21

↑

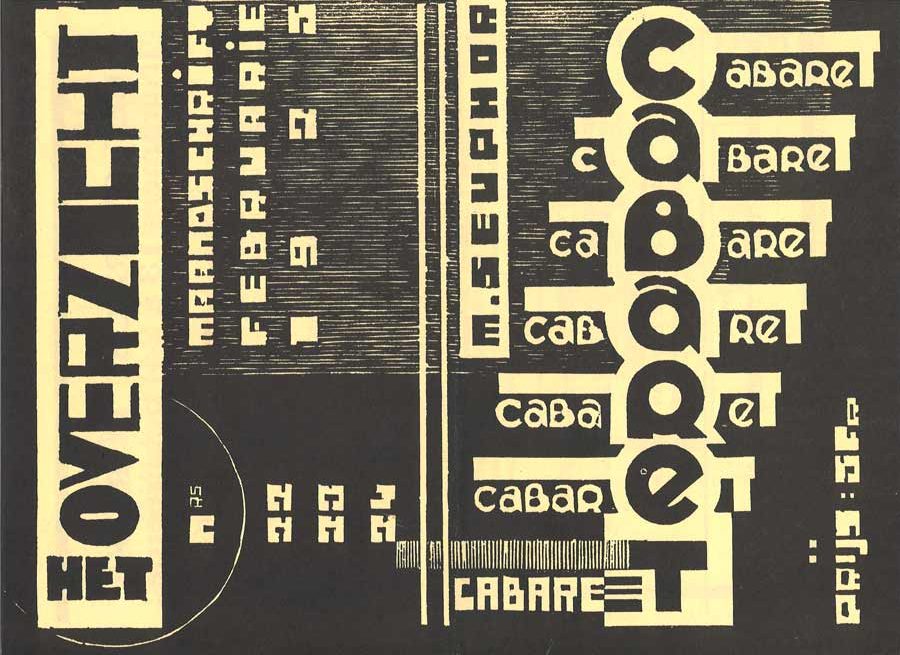

Het Overzicht

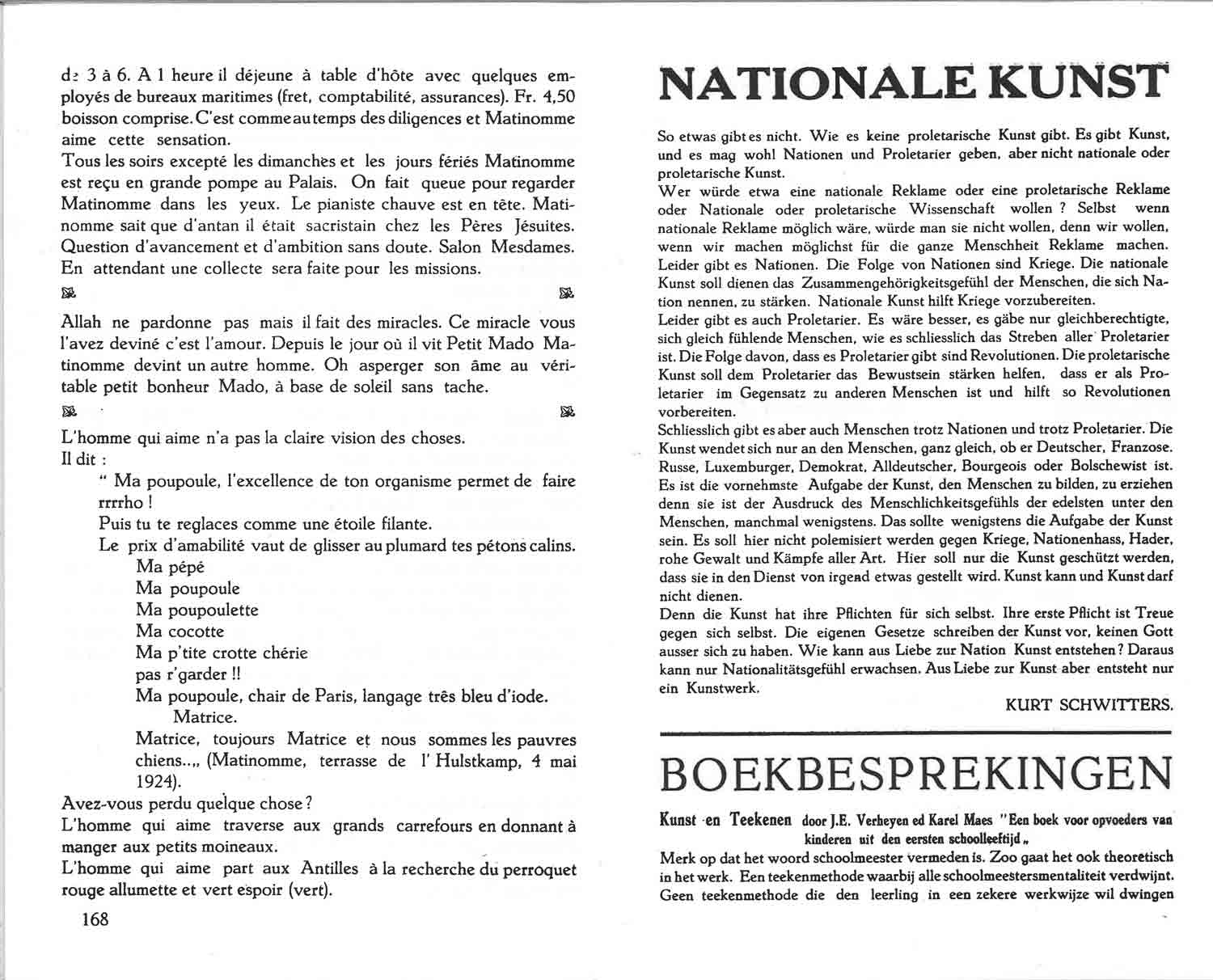

Nationale Kunst, Kurt Schwitters, Het Overzicht, Cabaret

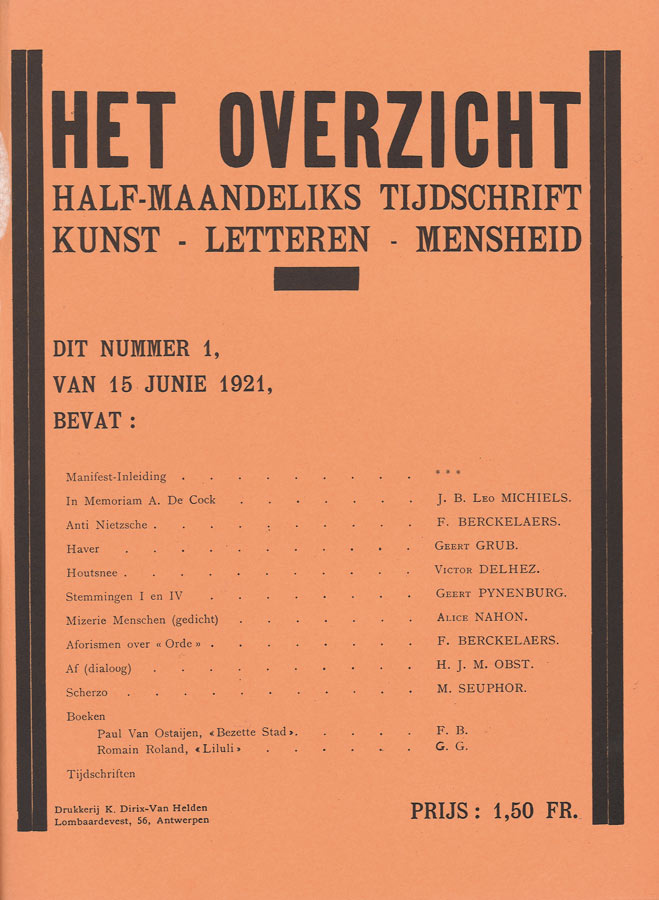

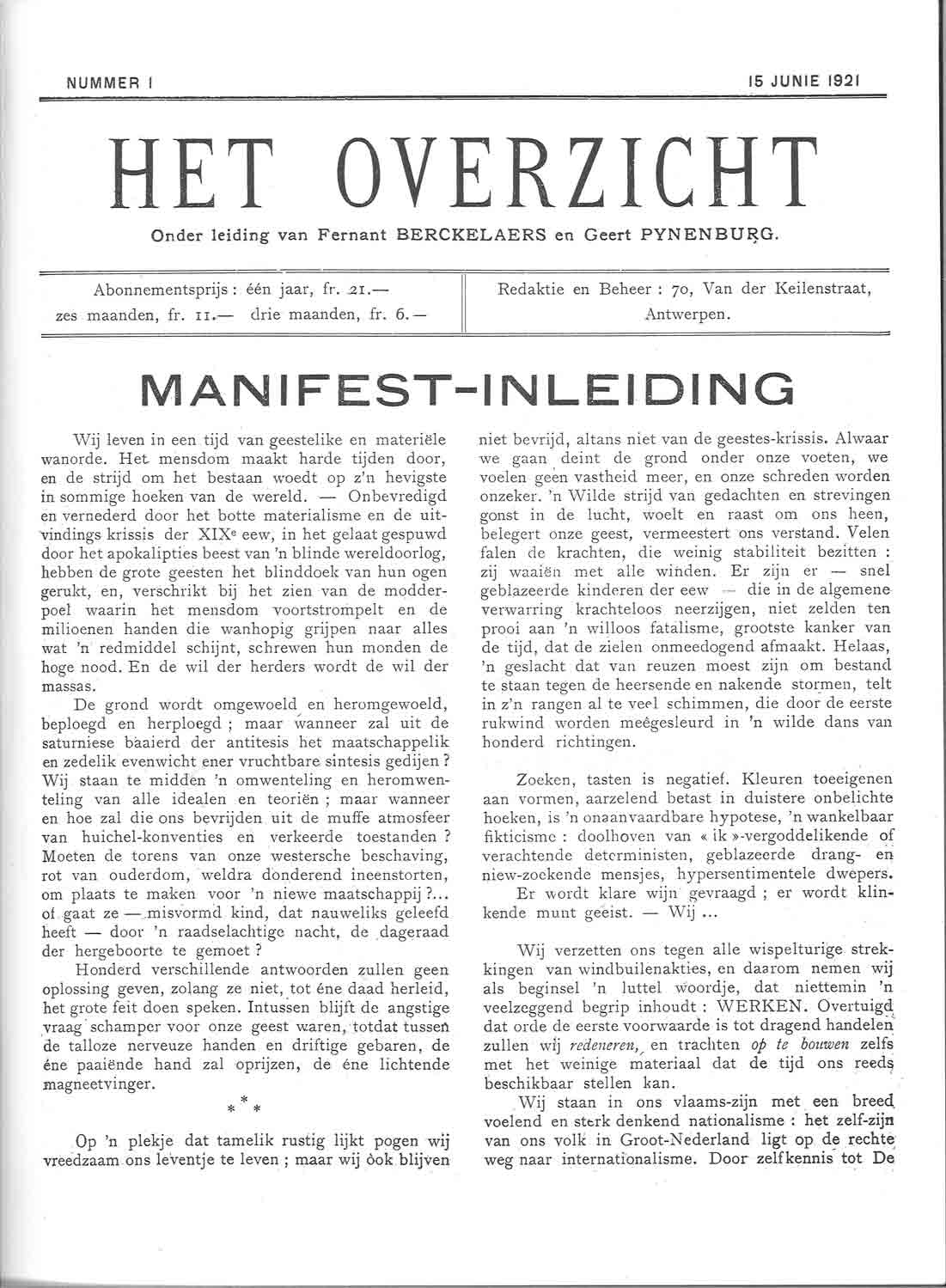

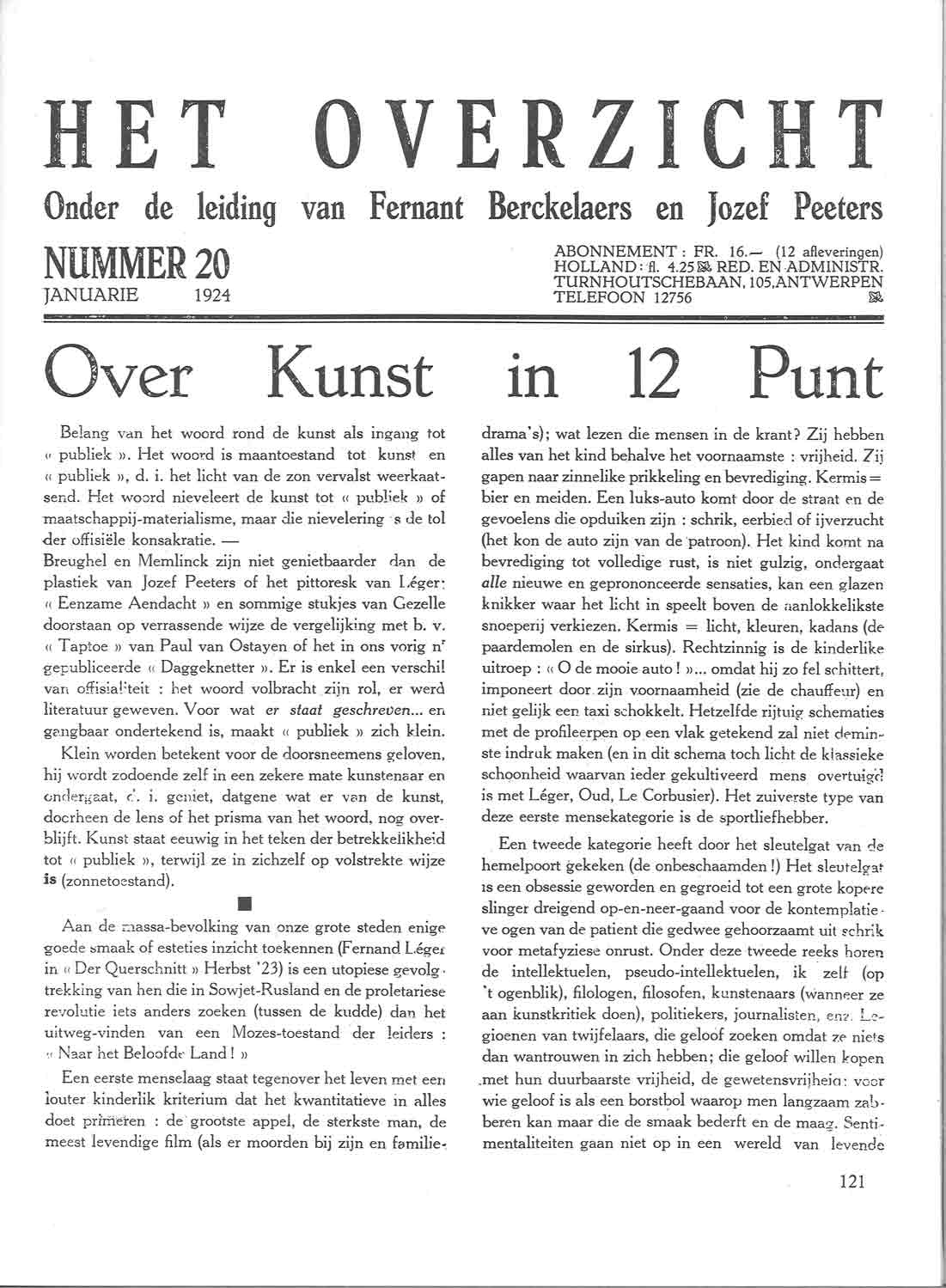

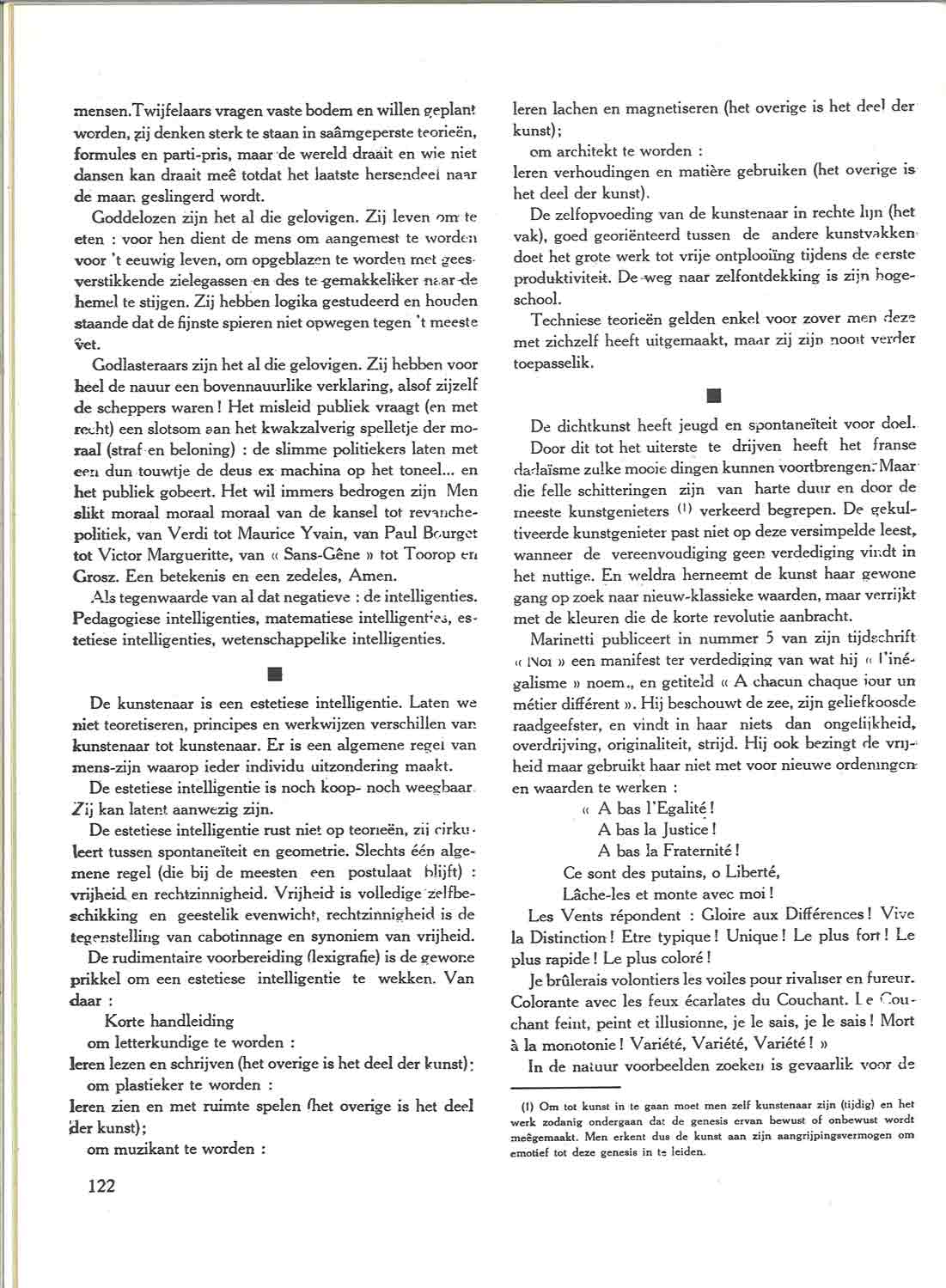

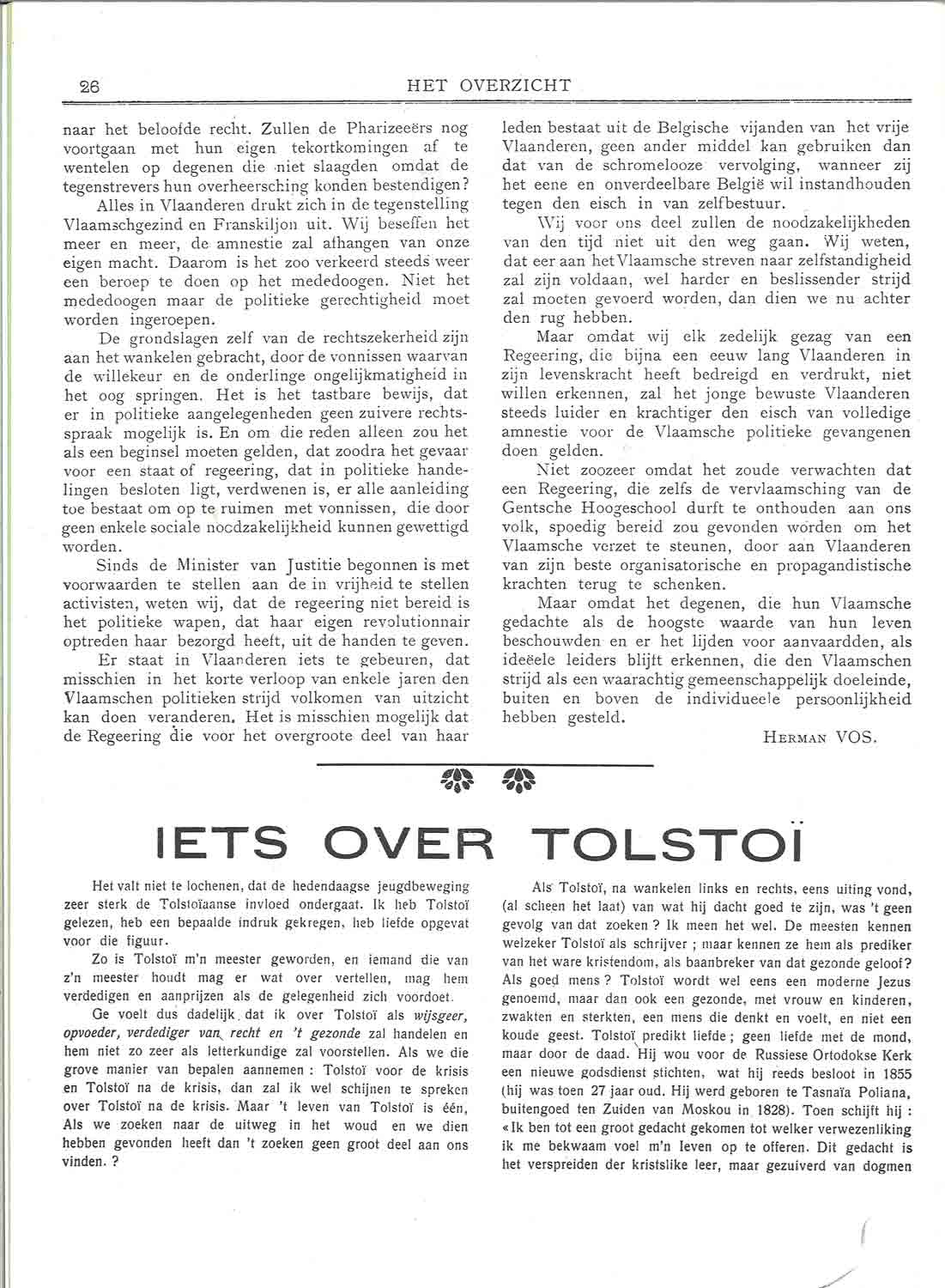

HET OVERZICHT

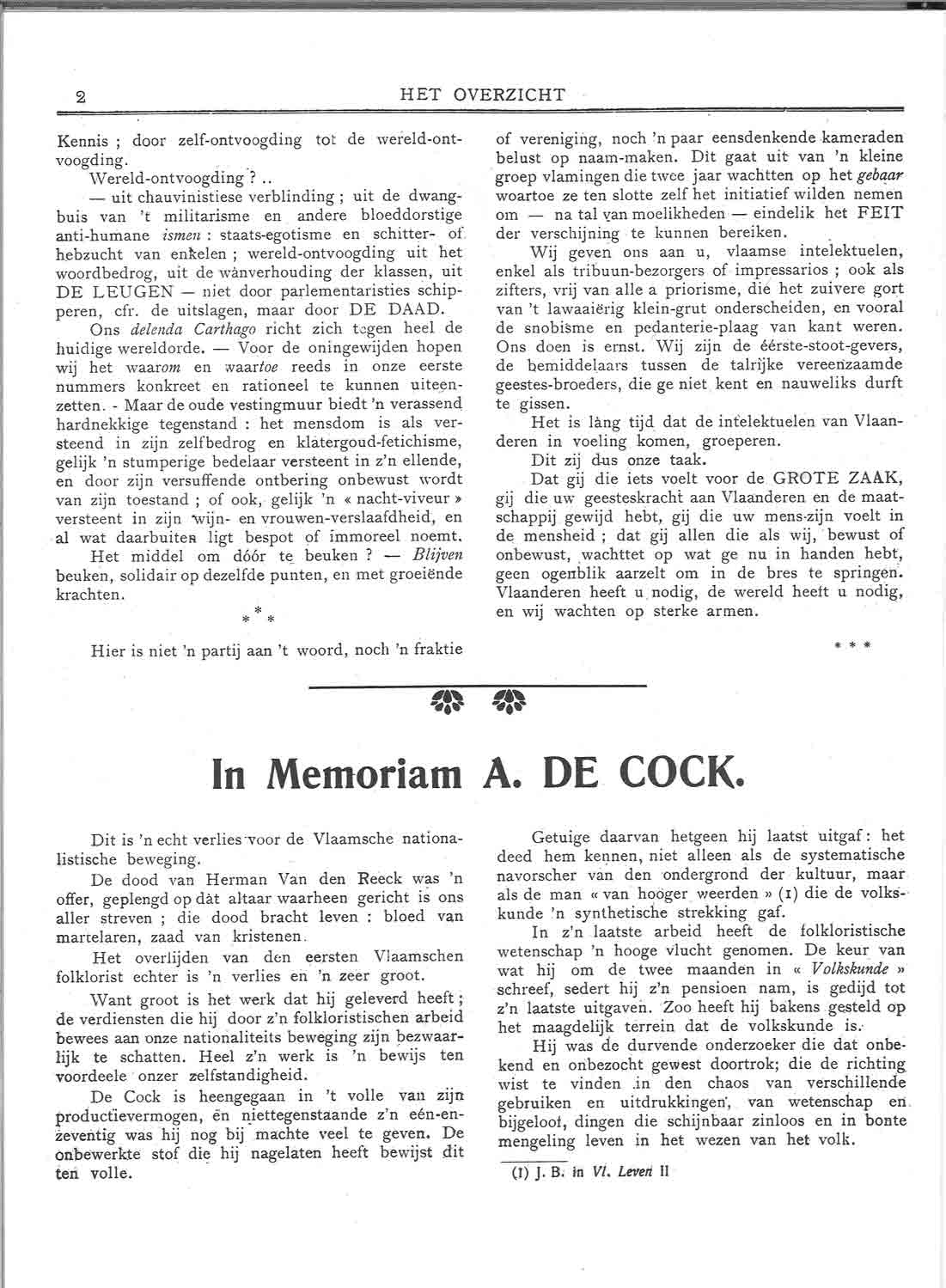

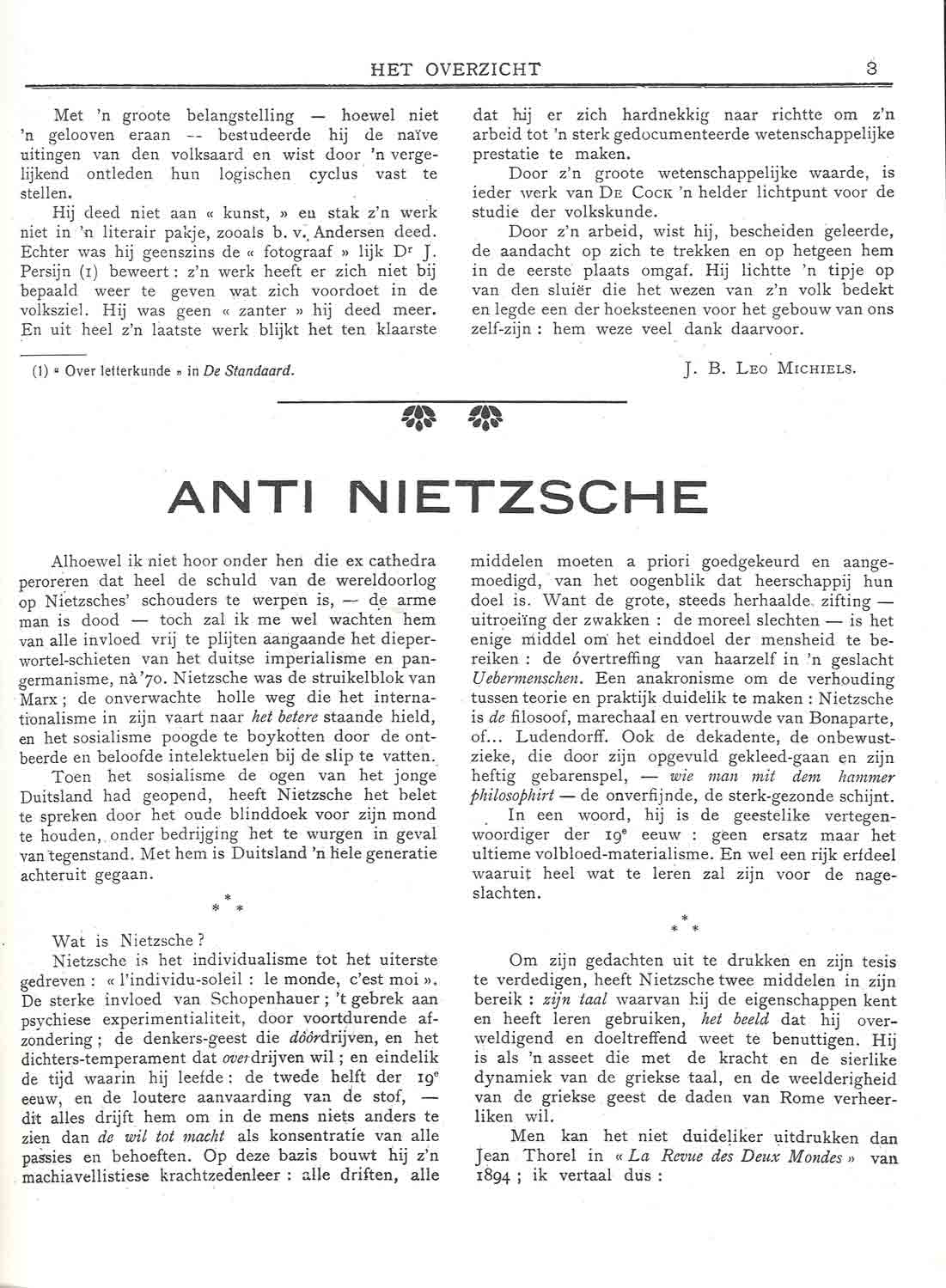

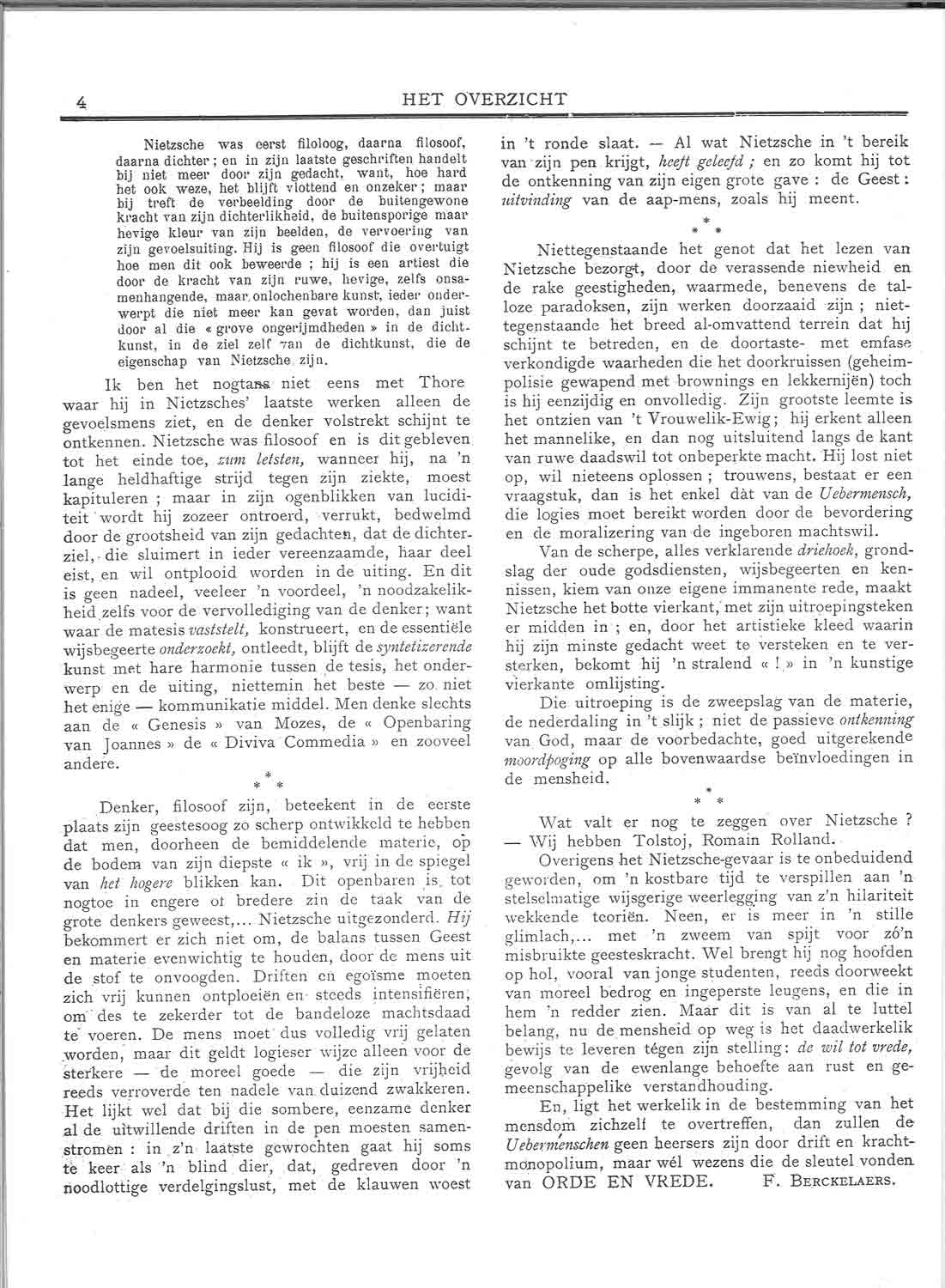

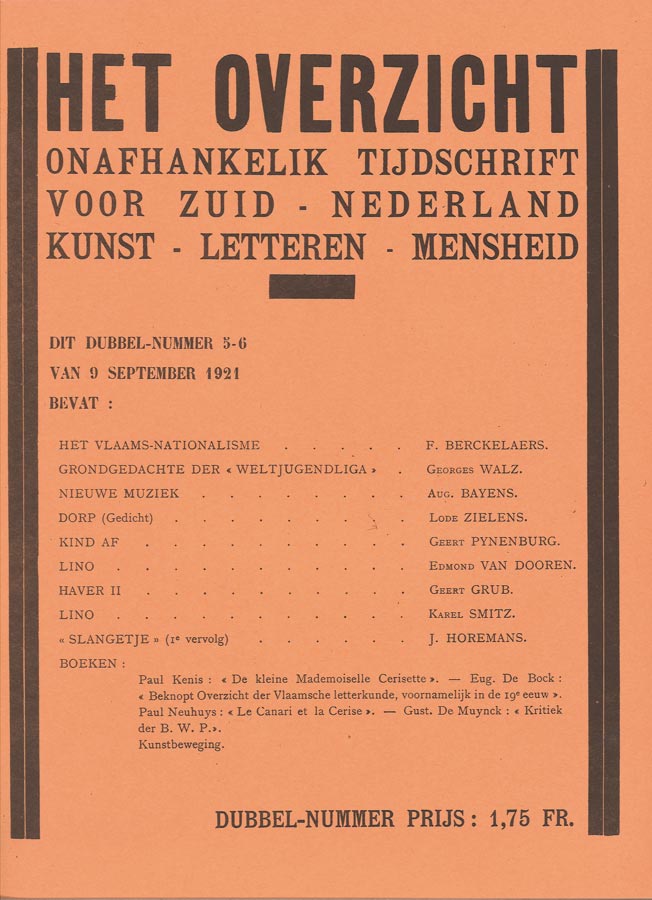

In parallel with his fight for the defense of the Flemish language, the young Fernand Berckelaers continued to read widely and acquired an increasingly universal consciousness. On this basis, he founded a new magazine in 1921: Het Overzicht (The Panorama), whose first issue came out on June 15. In this issue, Seuphor radically opposed the pangermanist ideas that plagued the Fleming activists.

« I rejected that, especially the idea of the ‘superman’, developed in the wake of Nietzsche. So much so that in the first issue of Het Overzicht, signed under my real name, Fernand Berckelaers, there is an article entitled Anti-Nietzsche, which opposes the superman. Humans with their possibilities, their greatness, and their weaknesses. But the superhuman, I don’t buy it!»

↑

Excerpt from

Michel Seuphor, un siècle de libertés

entretiens avec Alexandre Grenier, Hazan editions, 1996.

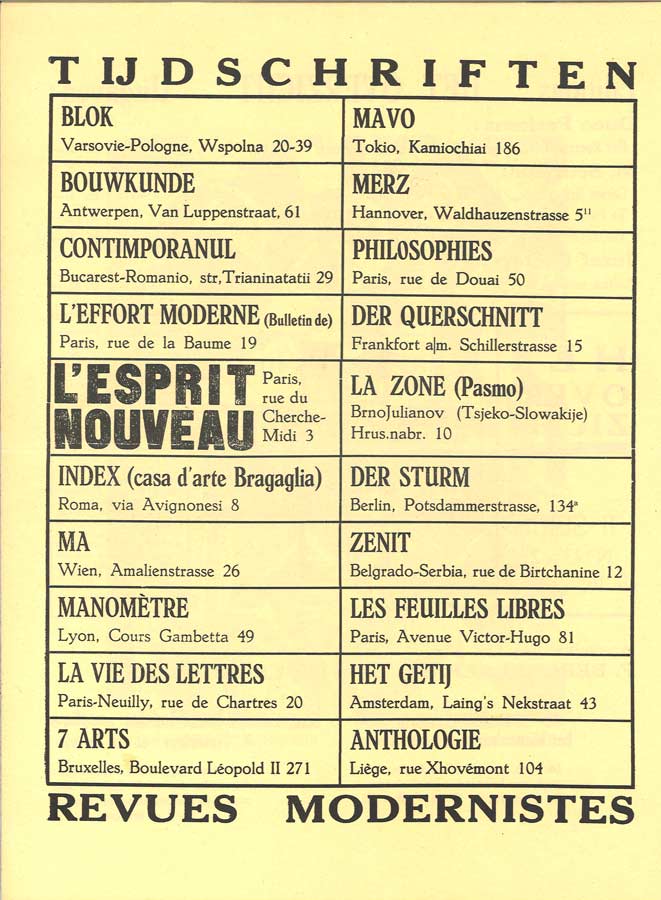

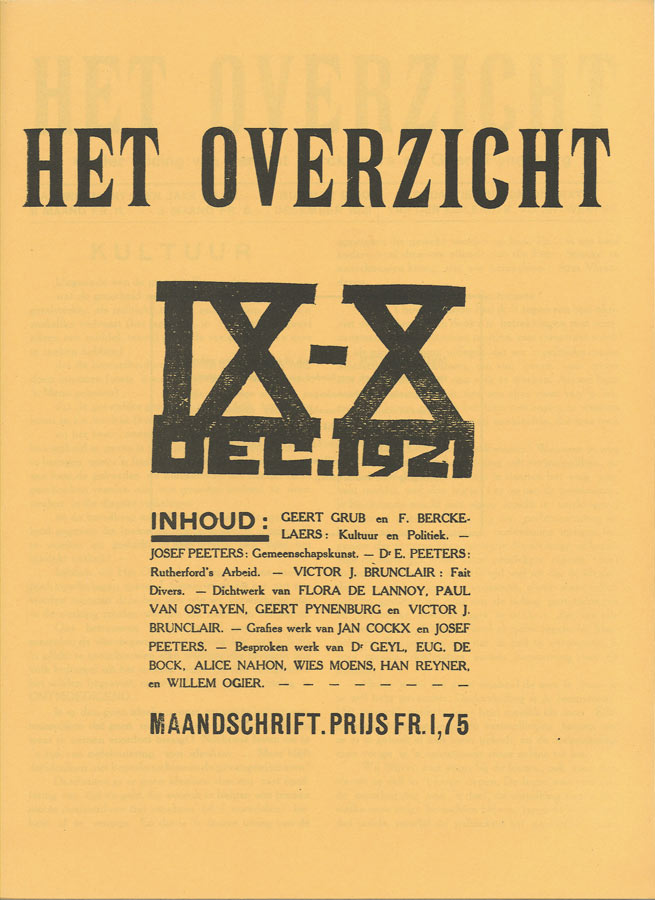

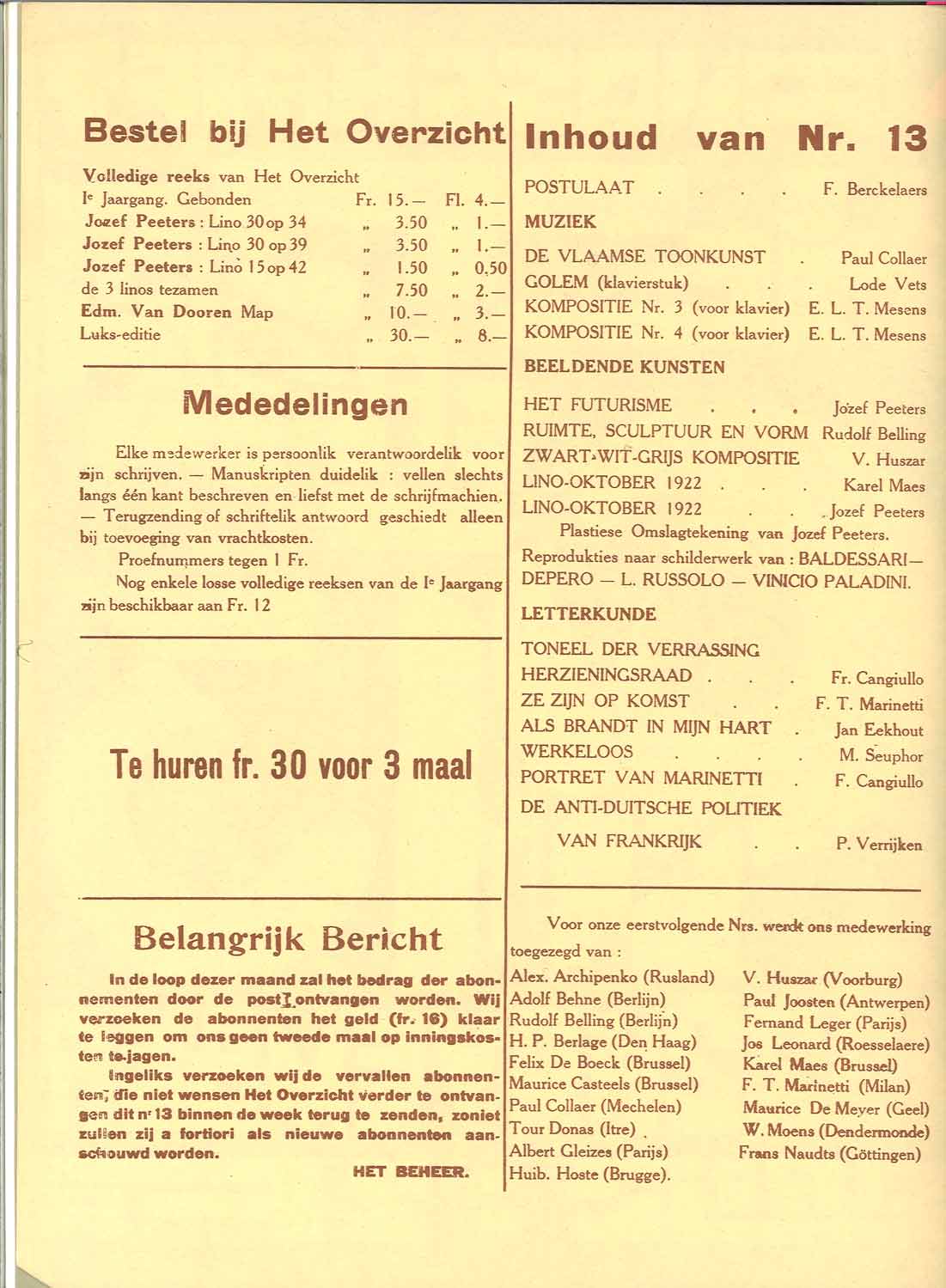

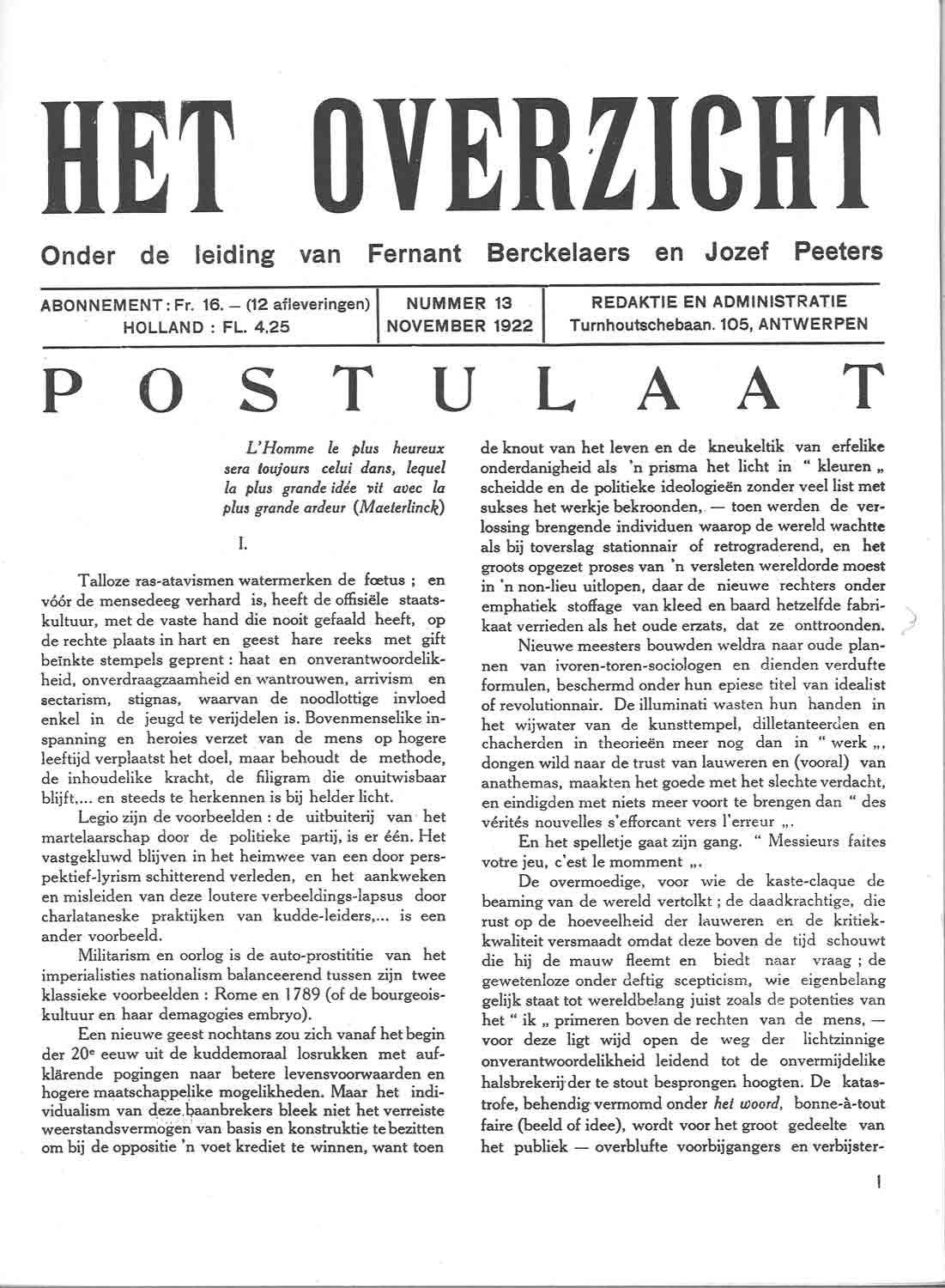

With Het Overzicht, Seuphor intends to break the rules of writing and broaden his horizon. He discovered pacifism, in particular through the writings of Romain Rolland, and shares his ideas with a small handful of friends. Their motto: « never war again!» And this goes far beyond, for him, the importance of Flemingism. He became passionately anti-nationalist and defended his ideas until the seventh issue of the magazine, which then became much more open to art and the plastic avant-garde. The conference given by Theo van Doesburg, who developed Mondrian’s philosophy of neoplasticism at the Antwerp Athenaeum in 1921, was the event that transformed the young Seuphor. From that moment on, he associated the Antwerp painter Joseph Peeters to the direction of the magazine and began exchanges with all the other European avant-garde magazines: Der Sturm, De Stijl, L’esprit nouveau, The little revue, Les feuilles libres. His poems and articles became exclusively signed under his pseudonym Seuphor. Because he saw Dadaism as a universal tendency towards abstraction, from 1922 onward he got in touch with the supporters of Dadaism, inviting Kurt Schwitters and Tristan Tzara to collaborate.

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 5-6-9, Septembre 1921

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 9-10, Décembre 1921

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 13, Novembre 1922

Couverture de J. Peeters

↑

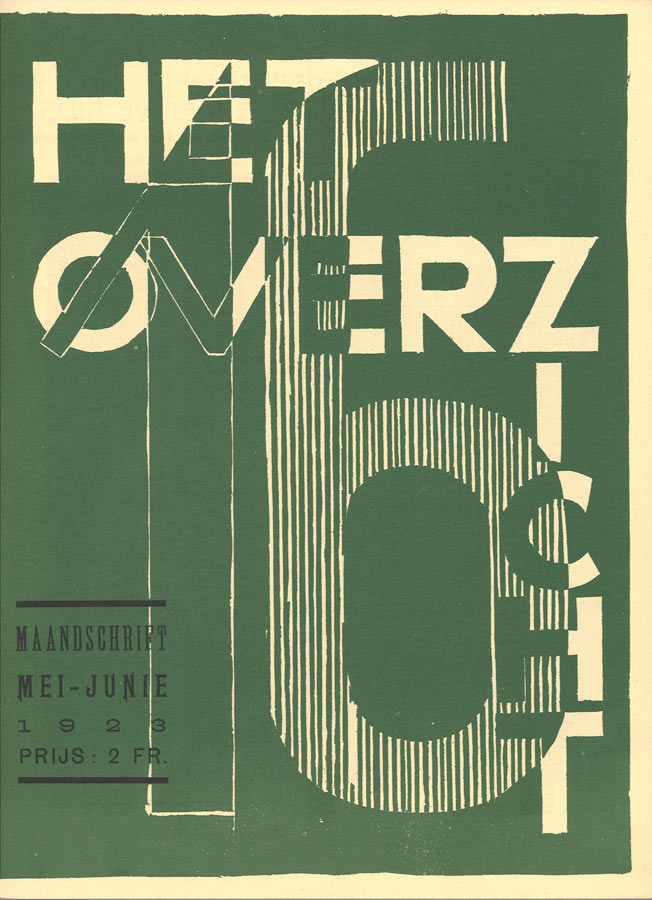

Het Overzicht

n° 16, Mai-Juin 1922

Couverture L. Moholy-Nagy

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 18-19, Octobre 1923

Couverture Jos Leonard

↑

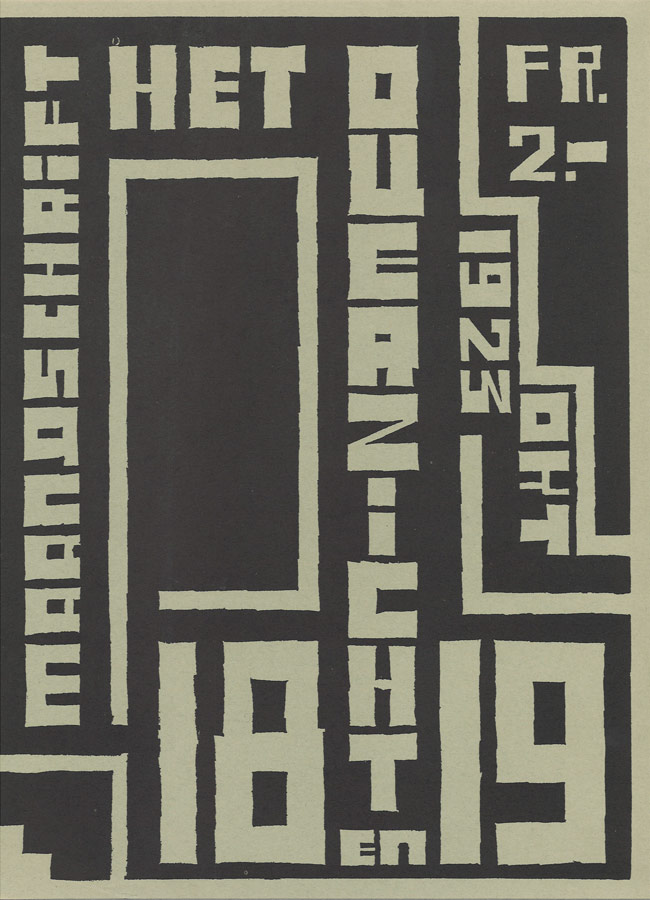

Het Overzicht

n° 18-19, Octobre 1923

Liste des contributeurs

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 21

Couverture J. J. P. Oud

HET OVERZICHT

In parallel with his fight for the defense of the Flemish language, the young Fernand Berckelaers continued to read widely and acquired an increasingly universal consciousness. On this basis, he founded a new magazine in 1921: Het Overzicht (The Panorama), whose first issue came out on June 15. In this issue, Seuphor radically opposed the pangermanist ideas that plagued the Fleming activists.

« I rejected that, especially the idea of the ‘superman’, developed in the wake of Nietzsche. So much so that in the first issue of Het Overzicht, signed under my real name, Fernand Berckelaers, there is an article entitled Anti-Nietzsche, which opposes the superman. Humans with their possibilities, their greatness, and their weaknesses. But the superhuman, I don’t buy it!»

↑

Excerpt from

Michel Seuphor, un siècle de libertés

entretiens avec Alexandre Grenier, Hazan editions, 1996.

With Het Overzicht, Seuphor intends to break the rules of writing and broaden his horizon. He discovered pacifism, in particular through the writings of Romain Rolland, and shares his ideas with a small handful of friends. Their motto: « never war again!» And this goes far beyond, for him, the importance of Flemingism. He became passionately anti-nationalist and defended his ideas until the seventh issue of the magazine, which then became much more open to art and the plastic avant-garde. The conference given by Theo van Doesburg, who developed Mondrian’s philosophy of neoplasticism at the Antwerp Athenaeum in 1921, was the event that transformed the young Seuphor. From that moment on, he associated the Antwerp painter Joseph Peeters to the direction of the magazine and began exchanges with all the other European avant-garde magazines: Der Sturm, De Stijl, L’esprit nouveau, The little revue, Les feuilles libres. His poems and articles became exclusively signed under his pseudonym Seuphor. Because he saw Dadaism as a universal tendency towards abstraction, from 1922 onward he got in touch with the supporters of Dadaism, inviting Kurt Schwitters and Tristan Tzara to collaborate.

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 5-6-9, Septembre 1921

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 9-10, Décembre 1921

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 13, Novembre 1922

Couverture de J. Peeters

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 14, Décembre 1922

Couverture de J. Peeters

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 16, Mai-Juin 1922

Couverture L. Moholy-Nagy

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 16, Mai-Juin 1922

Te Parijs in trombe, M. Seuphor

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 18-19, Octobre 1923

Couverture Jos Leonard

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 18-19, Octobre 1923

Liste des contributeurs

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 21

Couverture J. J. P. Oud

↑

Het Overzicht

Carnet de Bric à Brac, n° 21

↑

Het Overzicht

Nationale Kunst, Kurt Schwitters, Het Overzicht, Cabaret

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 1, 15 juin 1921

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 2, 1921

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 3-4, Août 1921

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 7-8, Octobre 1921

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 12, Septembre 1922

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 15, Mars-Avril 1923

Couverture Servranckx

↑

Het Overzicht, n° 15, Mars-Avril 1923

De natuur, Zij, De mens, Hij

F. Berckelaers

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 17, 1923

Couverture de Delaunay

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 20

Couverture Willinks

↑

Het Overzicht

n° 22-23-24

Cabaret, Février 1925

Couverture J. Peeters

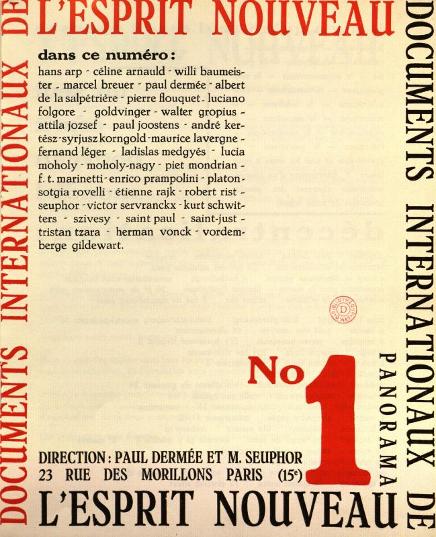

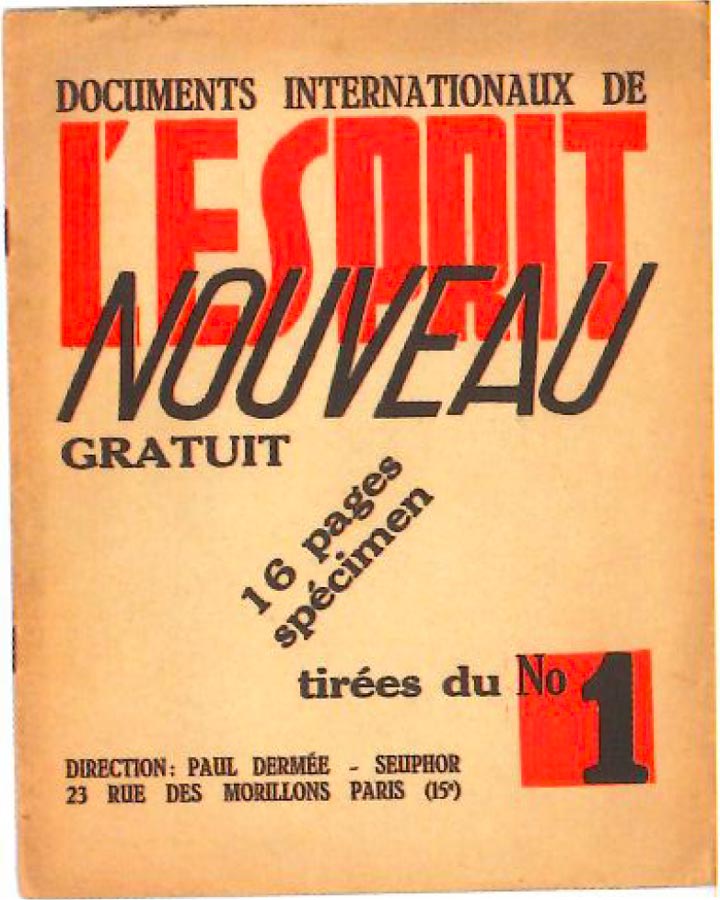

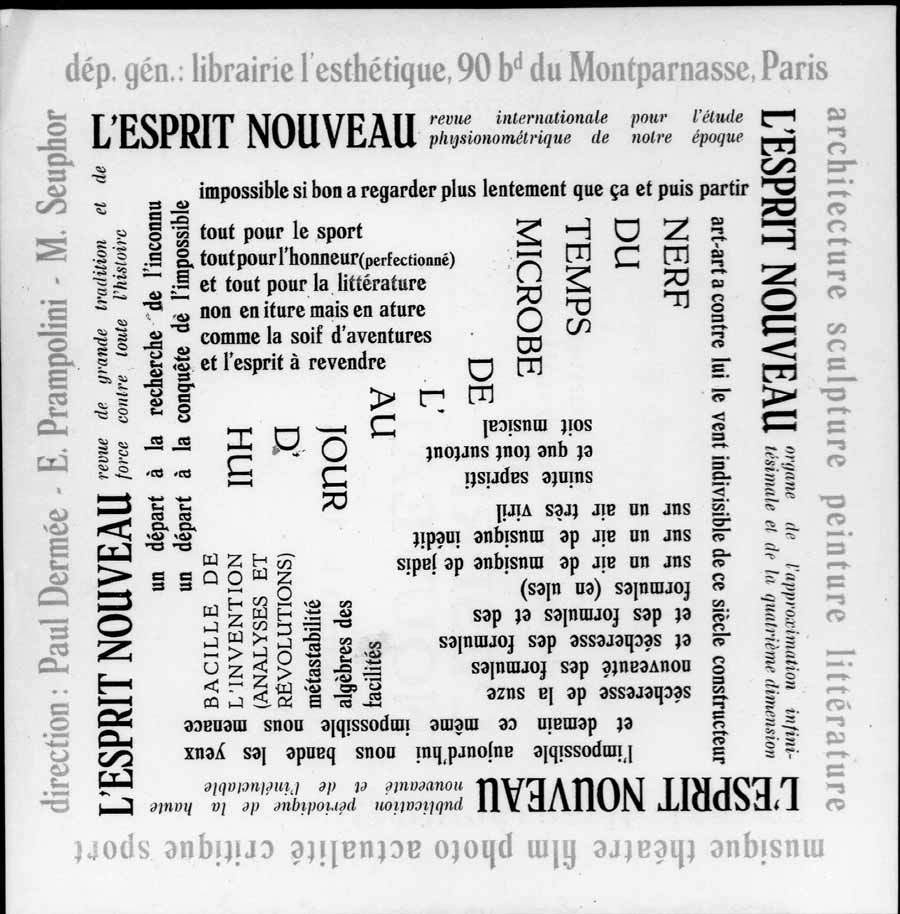

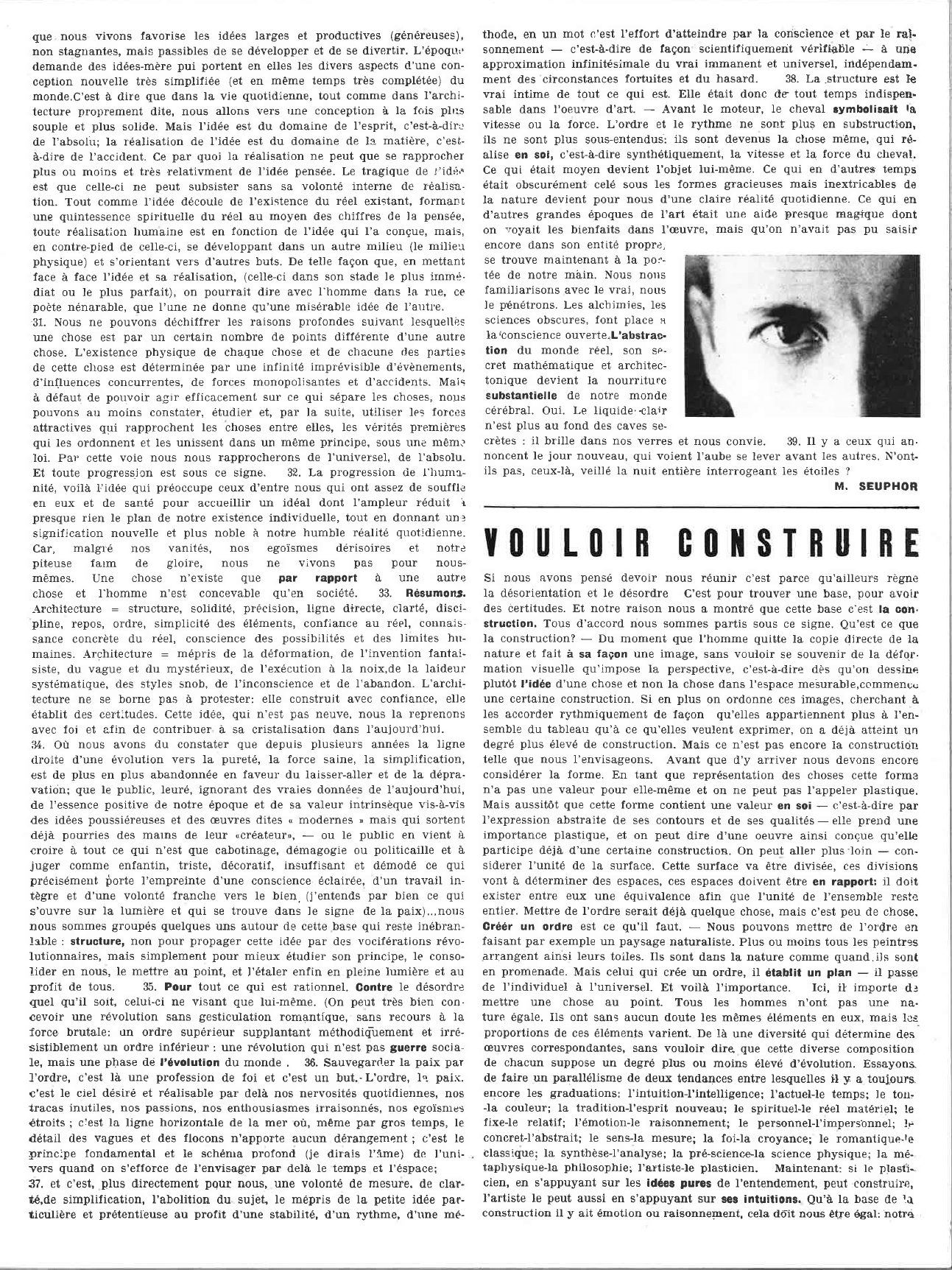

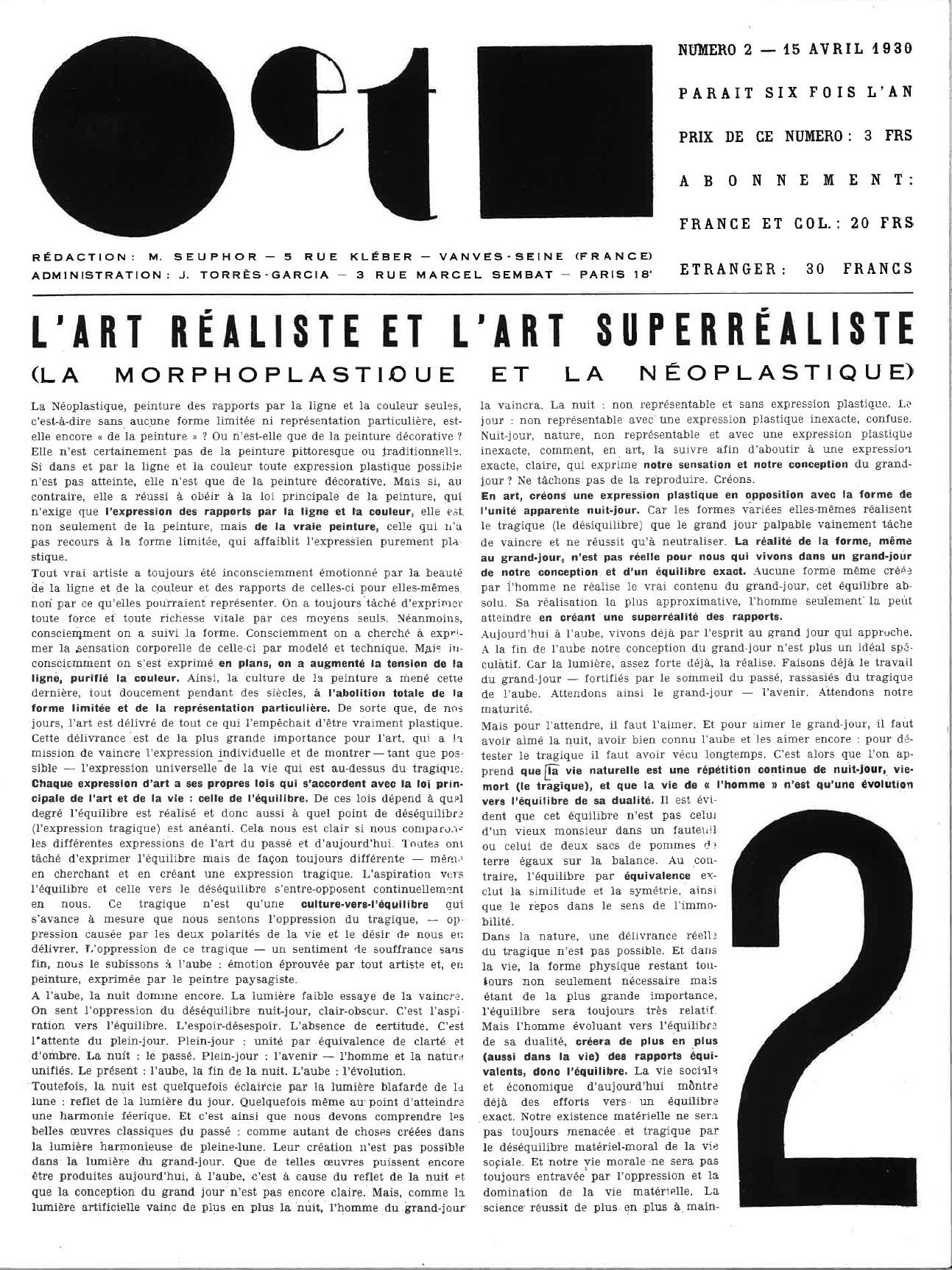

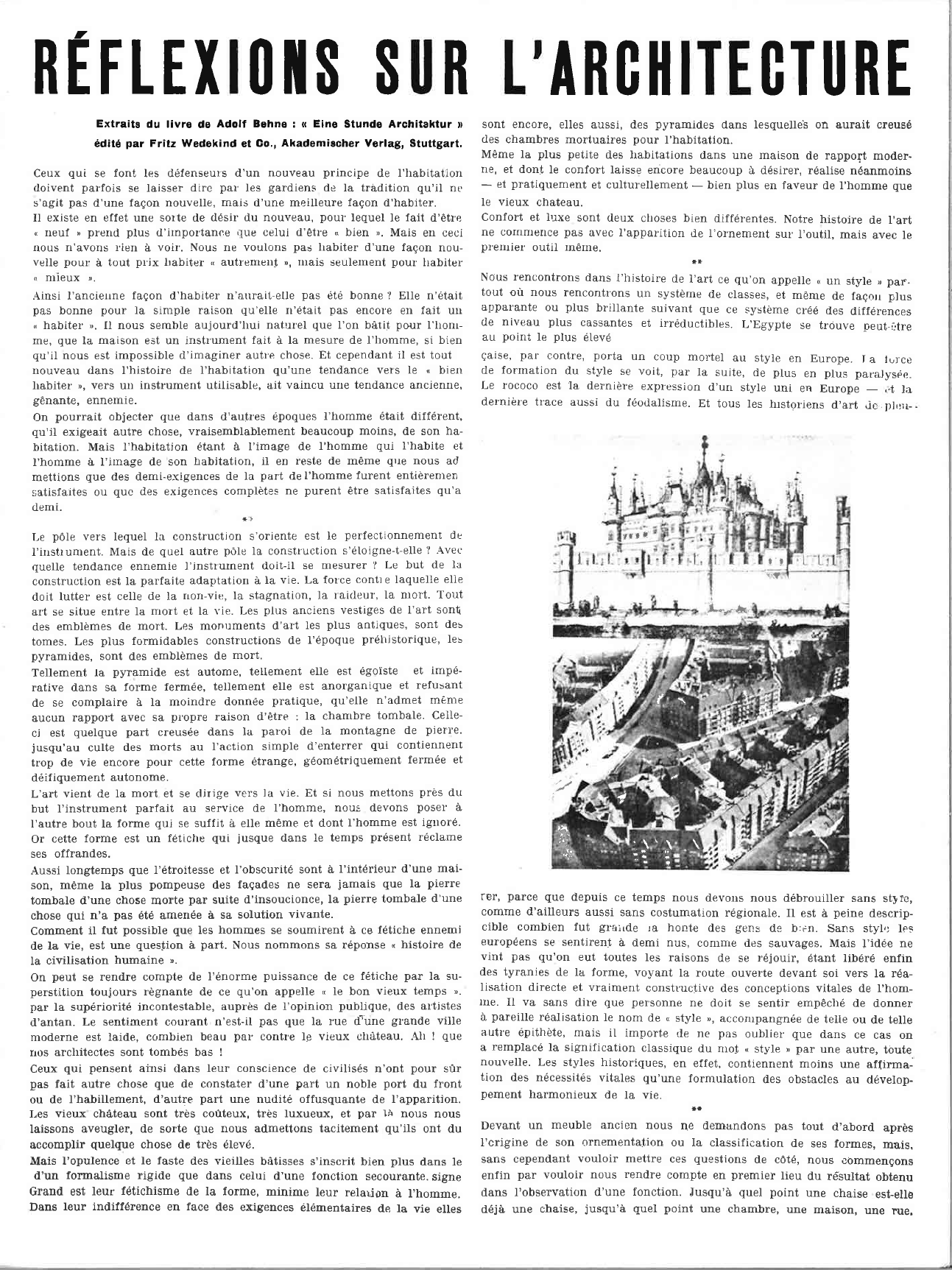

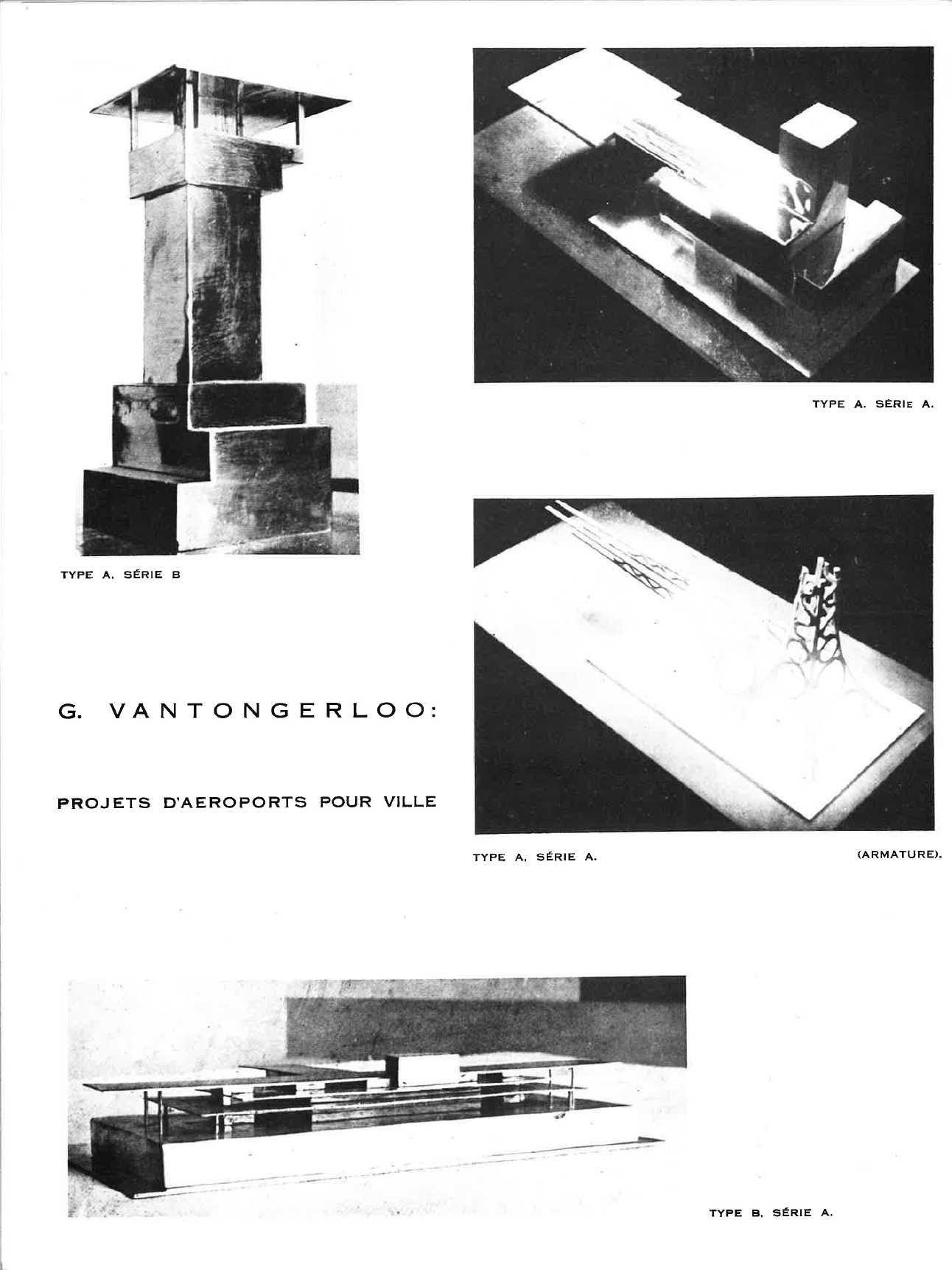

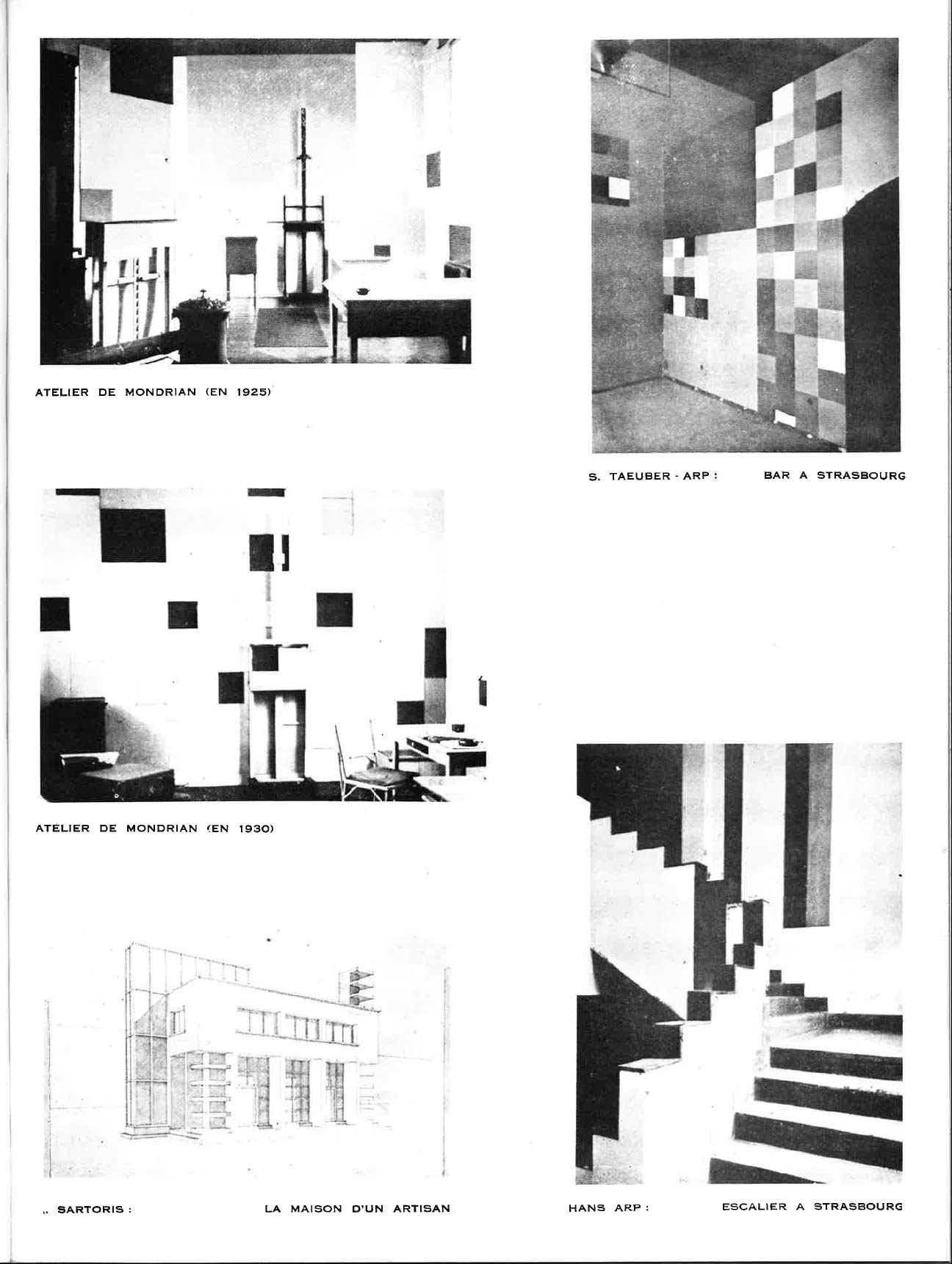

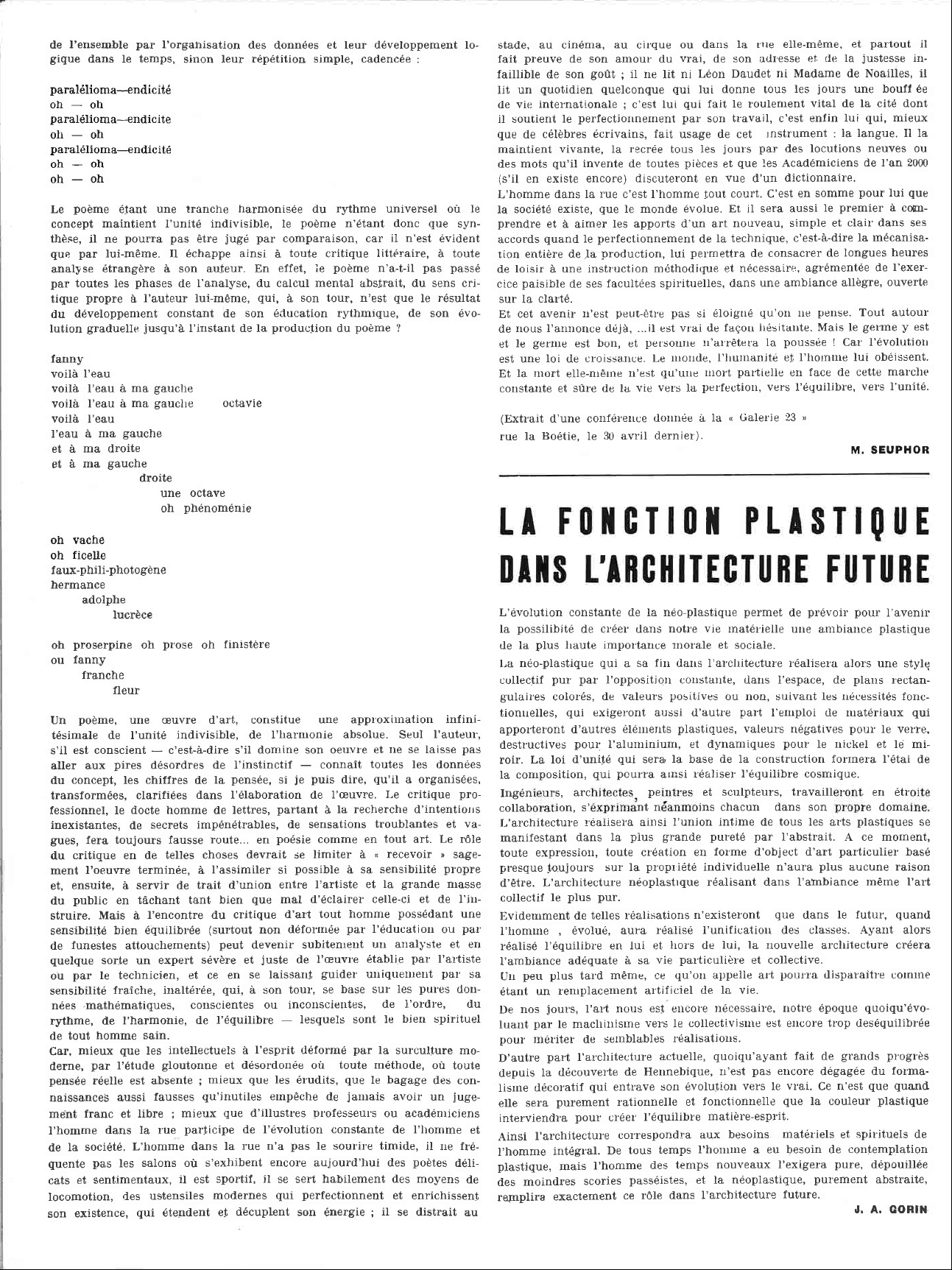

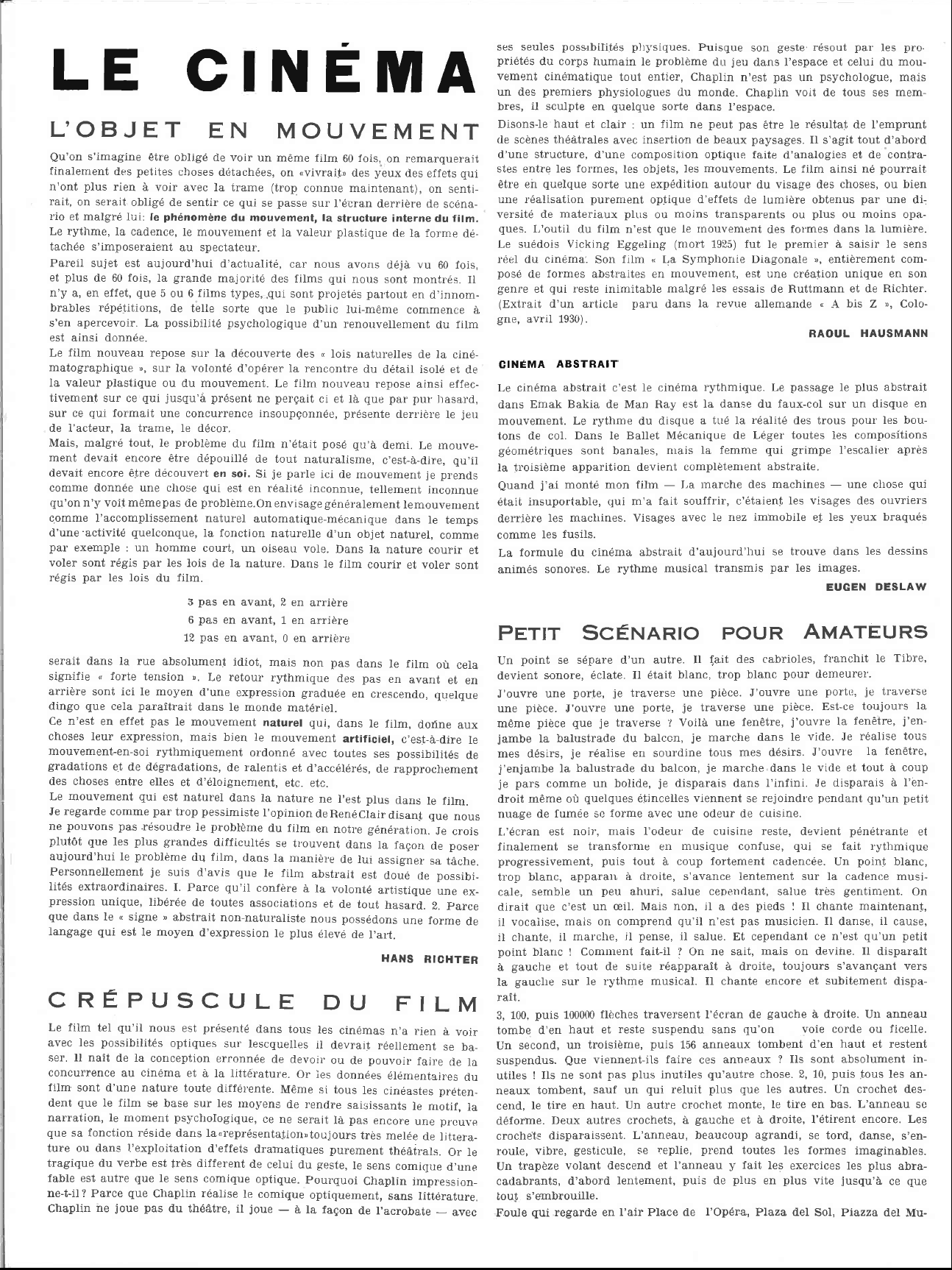

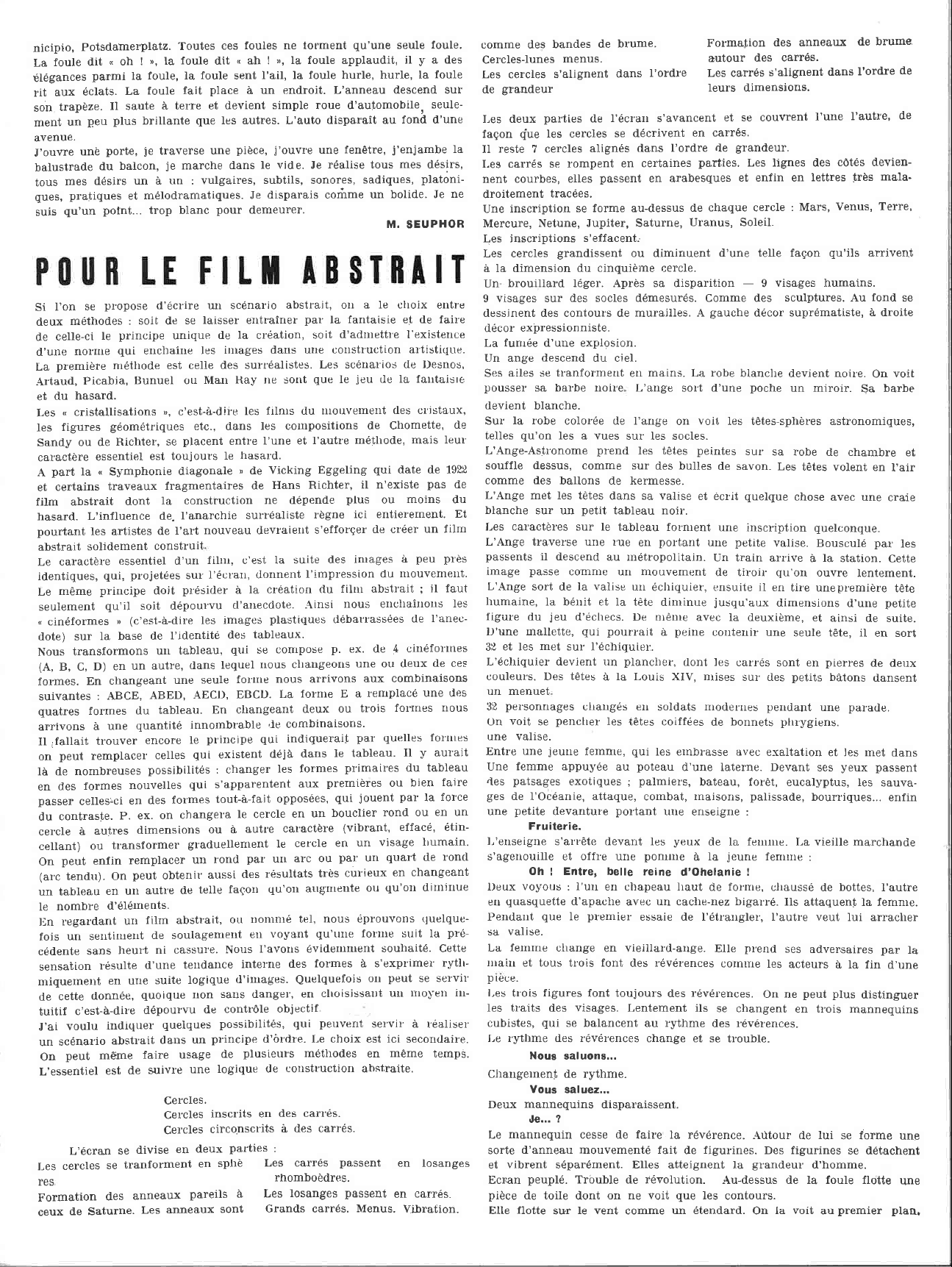

LES DOCUMENTS INTERNATIONAUX DE L’ESPRIT NOUVEAU

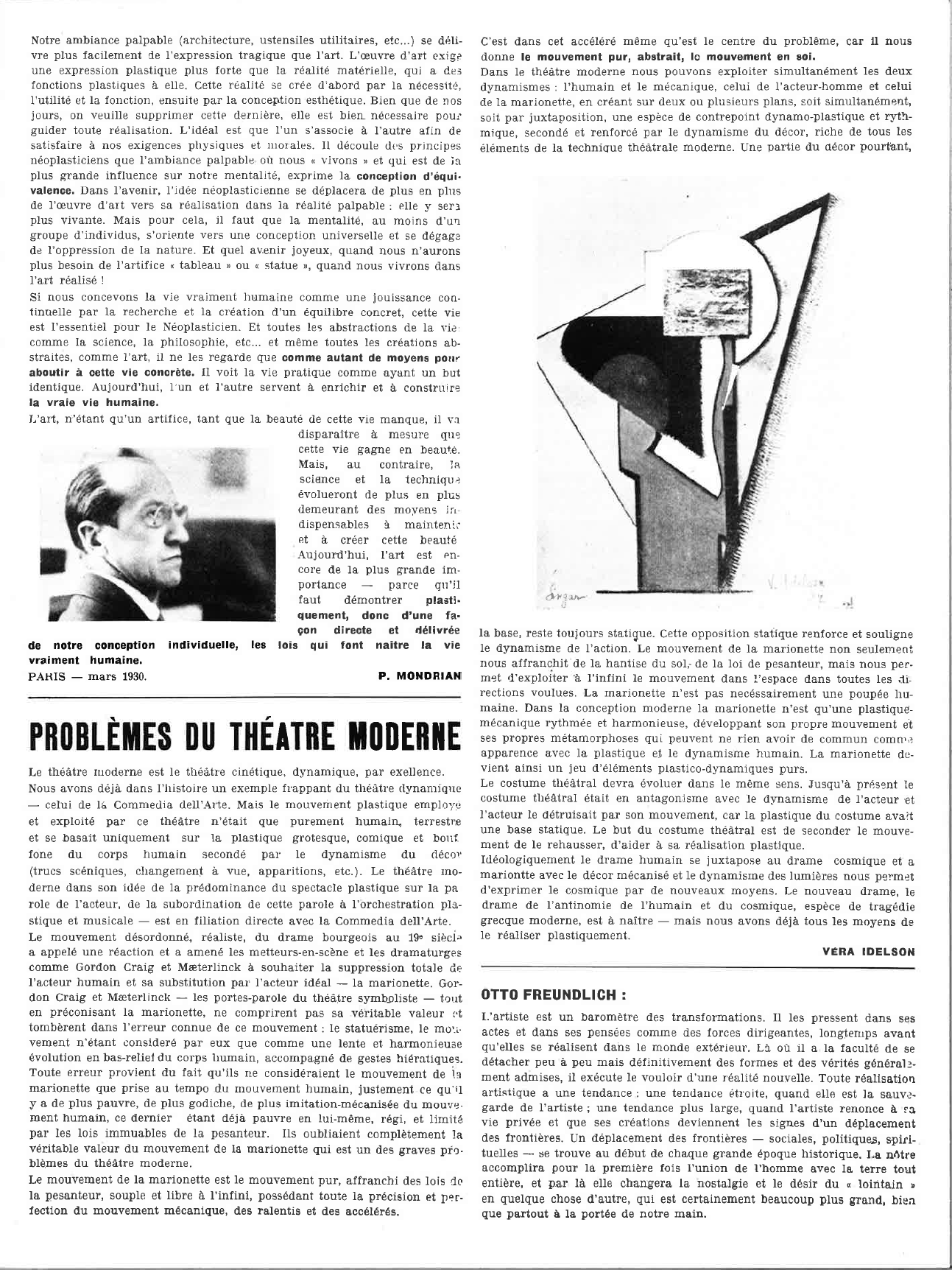

In 1925, Seuphor settled permanently in Paris. He put an end to Het Overzicht and began an extremely prolific period, rich in encounters, in particular with those who were to become the great masters of the art of this century: Mondrian, Schwitters, Delaunay, Arp, Taeuber, Léger, Vantongerloo, etc. Paul Dermée was one of his great friends, and it was with him that he created the magazine Les documents internationaux de l’esprit nouveau.

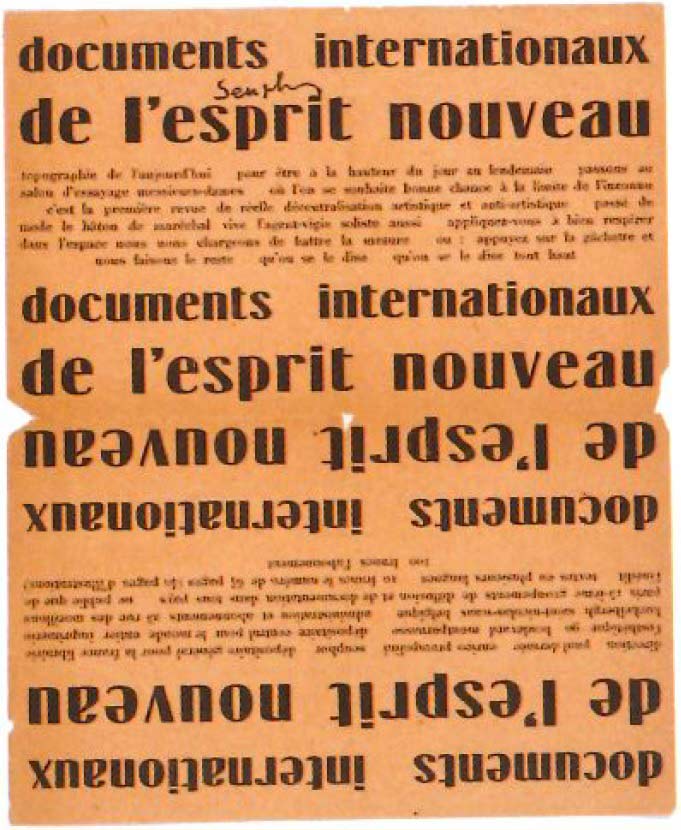

« During my visit to Paris in 1923, I had also met Le Corbusier in his studio. There I met Paul Dermée. He had been ousted from the journal L’Esprit Nouveau by Le Corbusier and Ozenfant, he had left… with the title, which belonged to him. This discord was very similar to the one I had with Peeters about Het Overzicht, a dispute about the orientation of the editorial content. Apparently, Le Corbusier and Ozenfant were pulling the magazine towards architecture and the plastic arts, their preoccupation, and Dermée did not accept it. But other interests were also grafted on this quarrel: the magazine was supported by the big industry, and Dermée’s preferences, who wanted that the literature as well represented as the plastic arts, did not serve the big business. This is why Le Corbusier and Ozenfant had not taken gloves with him… it is thus in association with Dermée, and Enrico Prampolini who joined us, that I resuscitated L’Esprit nouveau by adding the prefix International documents to it. ( … )

« The magazine was in the image of those who composed it: constructivist, futurist, expressionist and dadaist, as described in a leaflet that we had printed, destined to be « launched by plane» … but in fact that only the spectators of a theater received on their heads, from the balcony where we were! … documents internationaux de l’esprit nouveau, it was already Europe in the making. Paris, Rome, Berlin, The Hague, Antwerp, Weimar… in all these cities there were people who were working on the future, and our magazine had to talk about it. However, it has been forgotten. A few years ago, a large exhibition entitled « Paris ̶ Berlin» was held at Beaubourg. It was accompanied by a huge catalog, which was intended to reflect the exchanges and what was being done in these two cities in the first half of the century. At no point does it refer to the documents internationaux de l’esprit nouveau, and yet it was surely in 1927 one of the few links between the two cities. Unfortunately, the magazine had only one issue. It was not subsidized, like L’Esprit nouveau, by big business… but by the purse of an Italian countess, a friend of Prampolini. We never knew what happened between Prampolini and his countess, but the painter never got the money and the magazine went under.»

↑

Michel Seuphor, Un siècle de libertés,

1988. p 85-89

↑

Les documents internationaux de l'esprit nouveau

TractLES DOCUMENTS INTERNATIONAUX DE L’ESPRIT NOUVEAU

In 1925, Seuphor settled permanently in Paris. He put an end to Het Overzicht and began an extremely prolific period, rich in encounters, in particular with those who were to become the great masters of the art of this century: Mondrian, Schwitters, Delaunay, Arp, Taeuber, Léger, Vantongerloo, etc. Paul Dermée was one of his great friends, and it was with him that he created the magazine Les documents internationaux de l’esprit nouveau.

« During my visit to Paris in 1923, I had also met Le Corbusier in his studio. There I met Paul Dermée. He had been ousted from the journal L’Esprit Nouveau by Le Corbusier and Ozenfant, he had left… with the title, which belonged to him. This discord was very similar to the one I had with Peeters about Het Overzicht, a dispute about the orientation of the editorial content. Apparently, Le Corbusier and Ozenfant were pulling the magazine towards architecture and the plastic arts, their preoccupation, and Dermée did not accept it. But other interests were also grafted on this quarrel: the magazine was supported by the big industry, and Dermée’s preferences, who wanted that the literature as well represented as the plastic arts, did not serve the big business. This is why Le Corbusier and Ozenfant had not taken gloves with him… it is thus in association with Dermée, and Enrico Prampolini who joined us, that I resuscitated L’Esprit nouveau by adding the prefix International documents to it. ( … )

« The magazine was in the image of those who composed it: constructivist, futurist, expressionist and dadaist, as described in a leaflet that we had printed, destined to be « launched by plane» … but in fact that only the spectators of a theater received on their heads, from the balcony where we were! … documents internationaux de l’esprit nouveau, it was already Europe in the making. Paris, Rome, Berlin, The Hague, Antwerp, Weimar… in all these cities there were people who were working on the future, and our magazine had to talk about it. However, it has been forgotten. A few years ago, a large exhibition entitled « Paris ̶ Berlin» was held at Beaubourg. It was accompanied by a huge catalog, which was intended to reflect the exchanges and what was being done in these two cities in the first half of the century. At no point does it refer to the documents internationaux de l’esprit nouveau, and yet it was surely in 1927 one of the few links between the two cities. Unfortunately, the magazine had only one issue. It was not subsidized, like L’Esprit nouveau, by big business… but by the purse of an Italian countess, a friend of Prampolini. We never knew what happened between Prampolini and his countess, but the painter never got the money and the magazine went under.»

↑

Michel Seuphor, Un siècle de libertés,

1988. p 85-89

↑

Les documents internationaux de l'esprit nouveau

Tract•

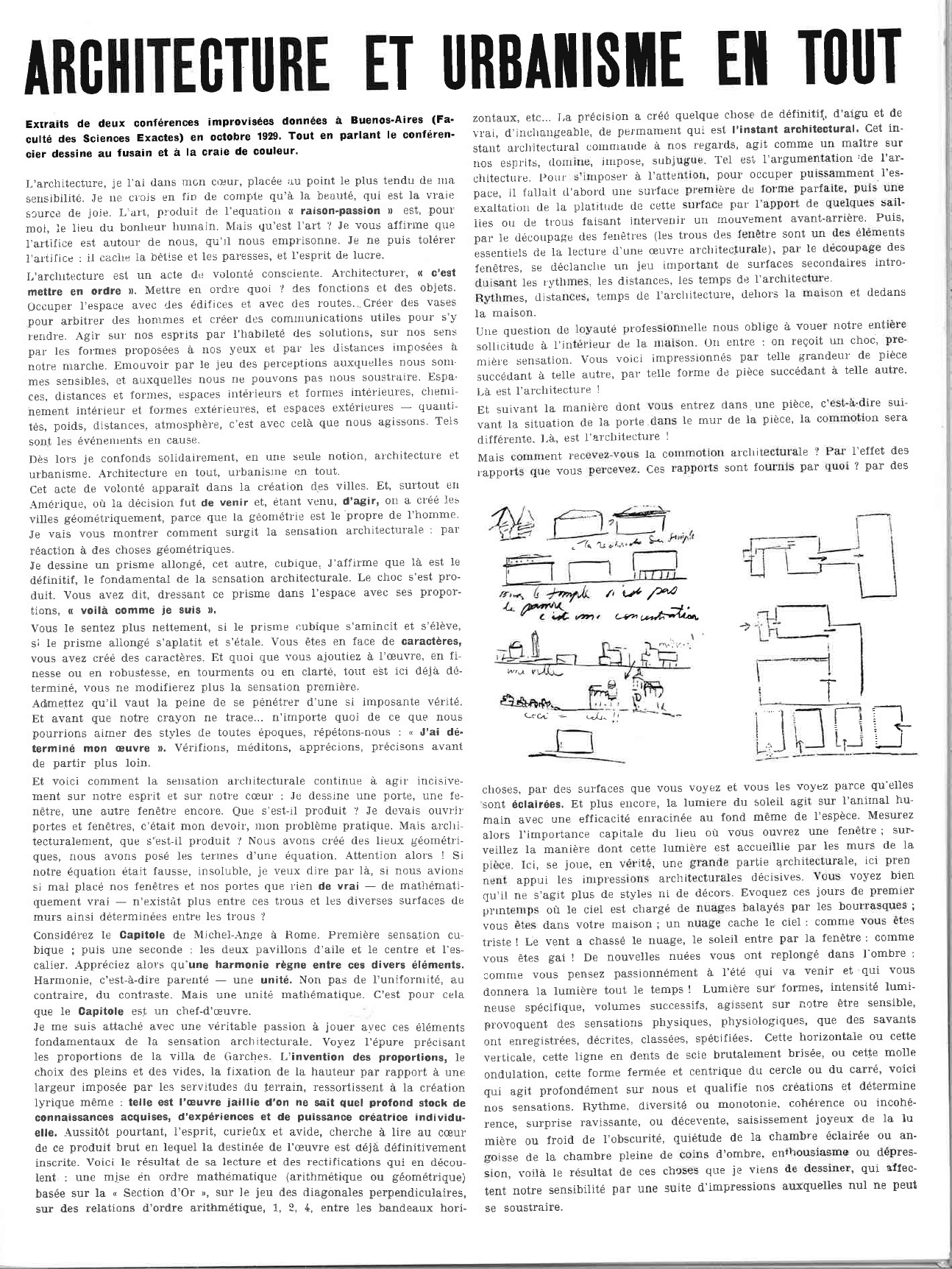

1930, a dinner at the restaurant Voltaire. From left to right R.Delaunay, Arp, Stazewsky, standing Giacelli, Florence Henri, Seuphor, Brzekowski, Pouma, Vantongerloo, Les Werner, S Taeuber, Mondrian, S.Delaunay

•

At Paul Dermée's in Paris, June 9, 1928. From left to right: Standing: Michel Seuphor, Piet Mondrian, Georges Vantongerloo, Luigi Ruissolo, Ilarie Voronca, Paul Dermée, Tysliava. Seated: Céline Arnaud, Rafalowski, Henri Stazewski

•

« Cercle et Carré »group in the basement of gallery 23. In the foreground, on the left, Antoine Pevsner, crouching next to the barrel: Michel Seuphor, and next to him, stooped, Hans Arp↑

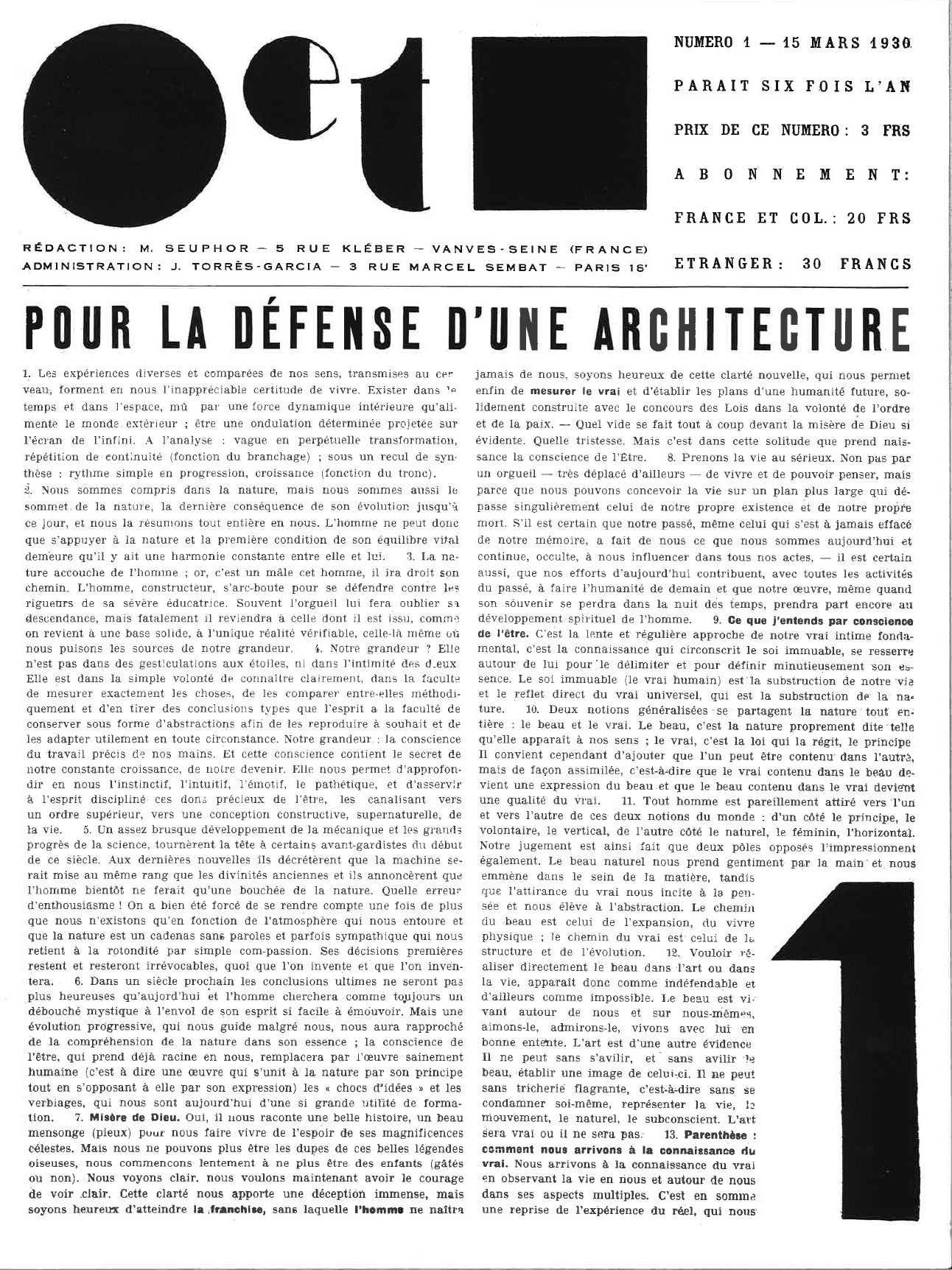

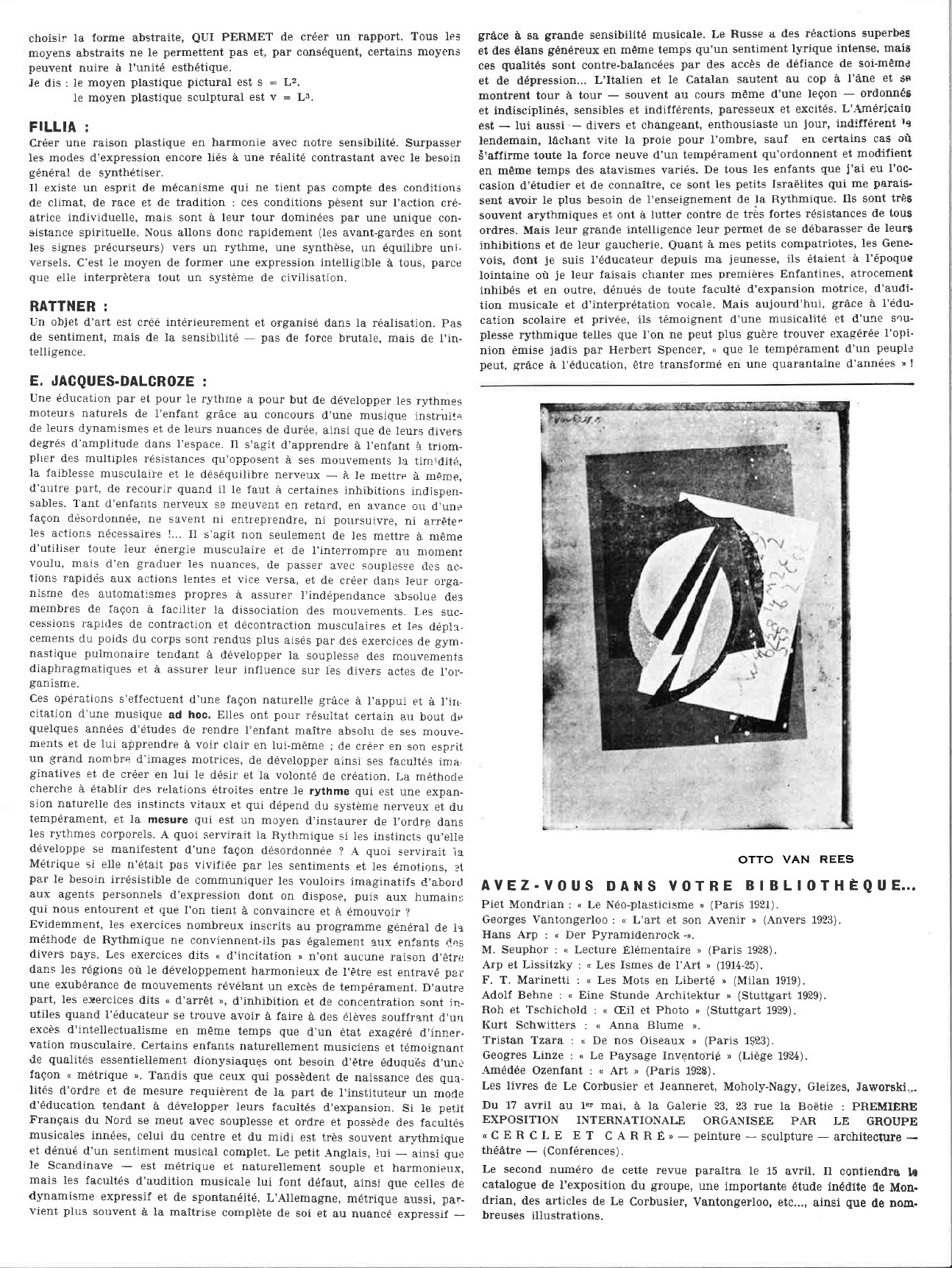

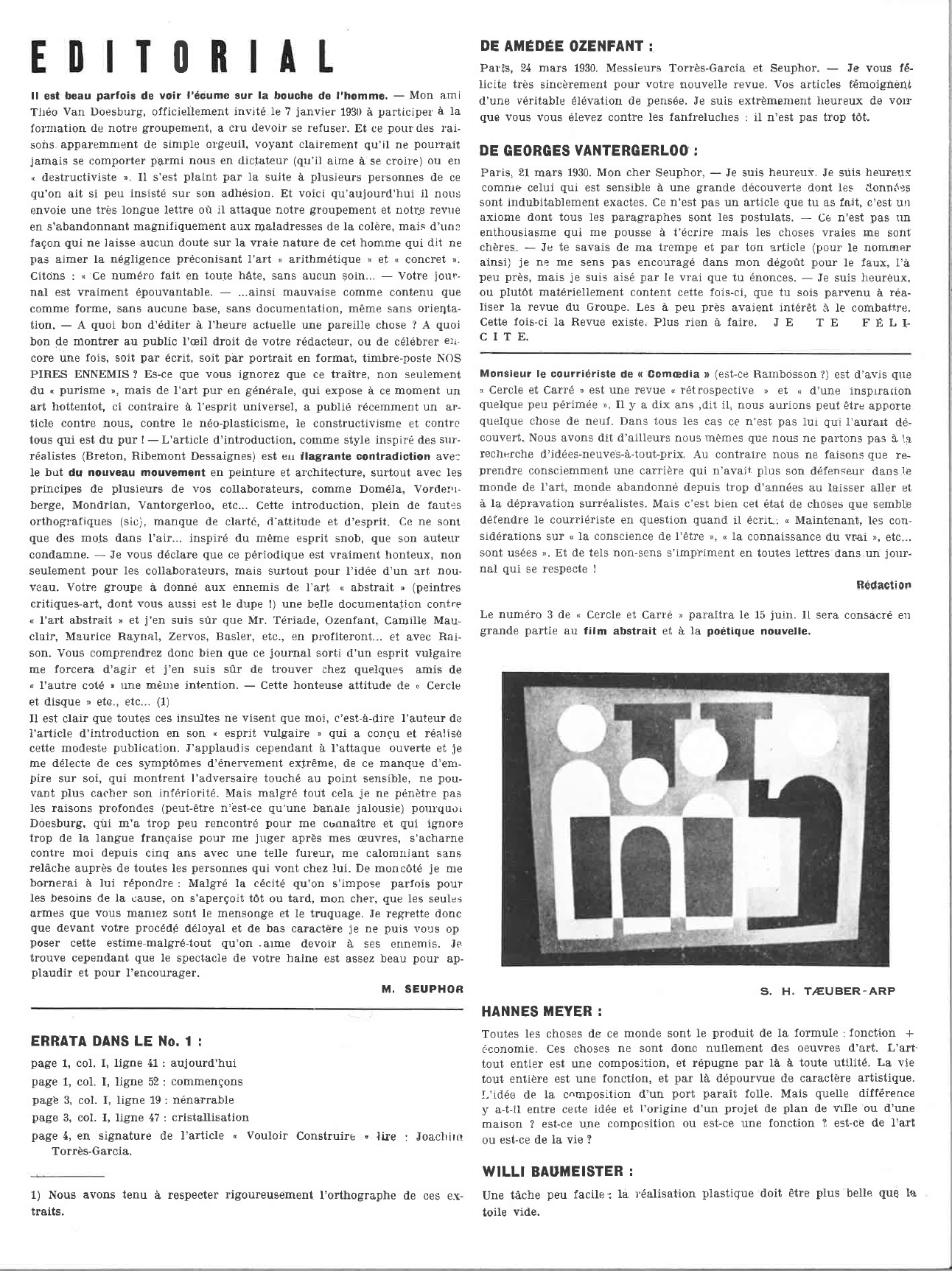

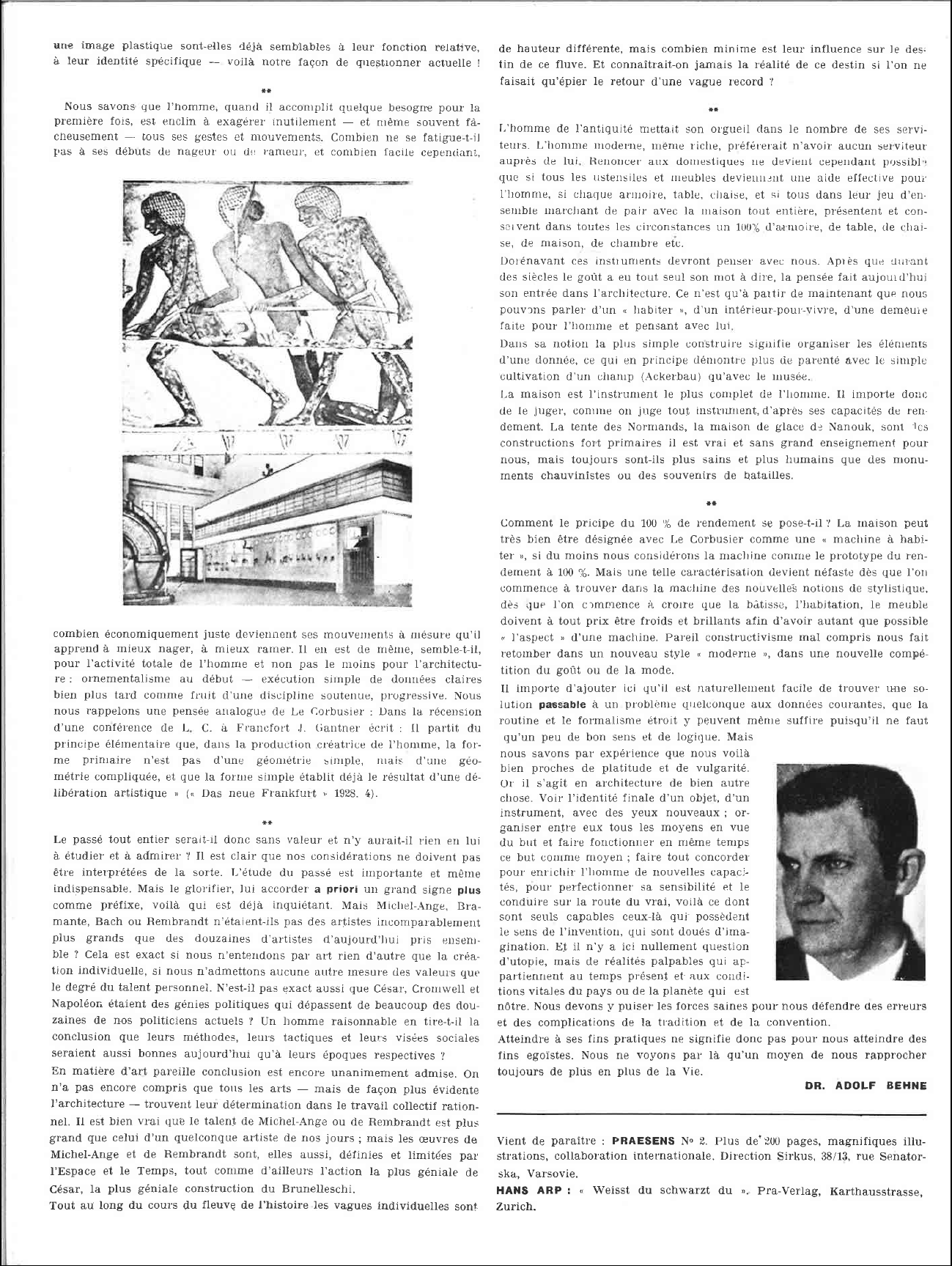

Cercle et carré

n° 1

↑

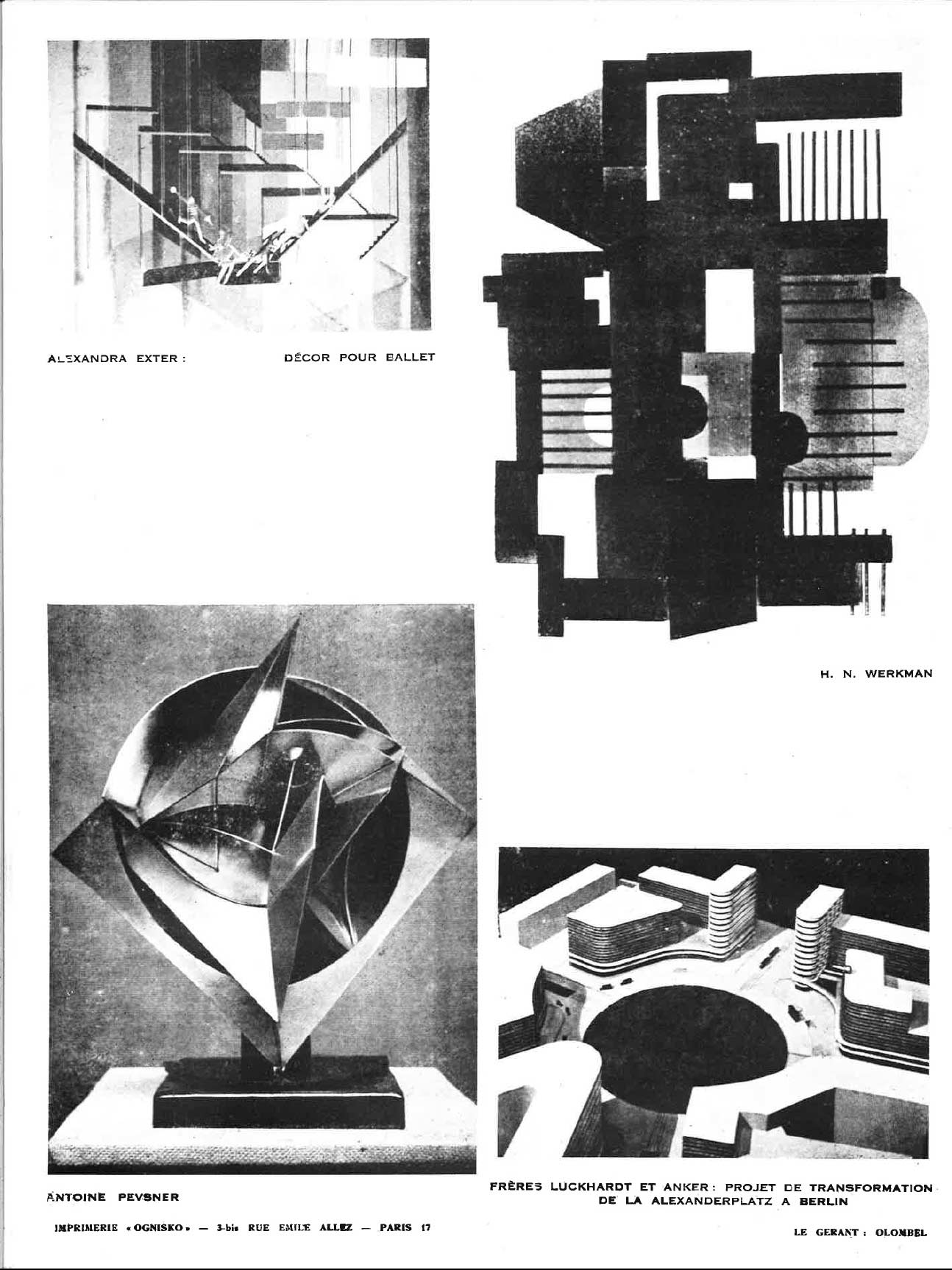

Cercle et carré

n°2

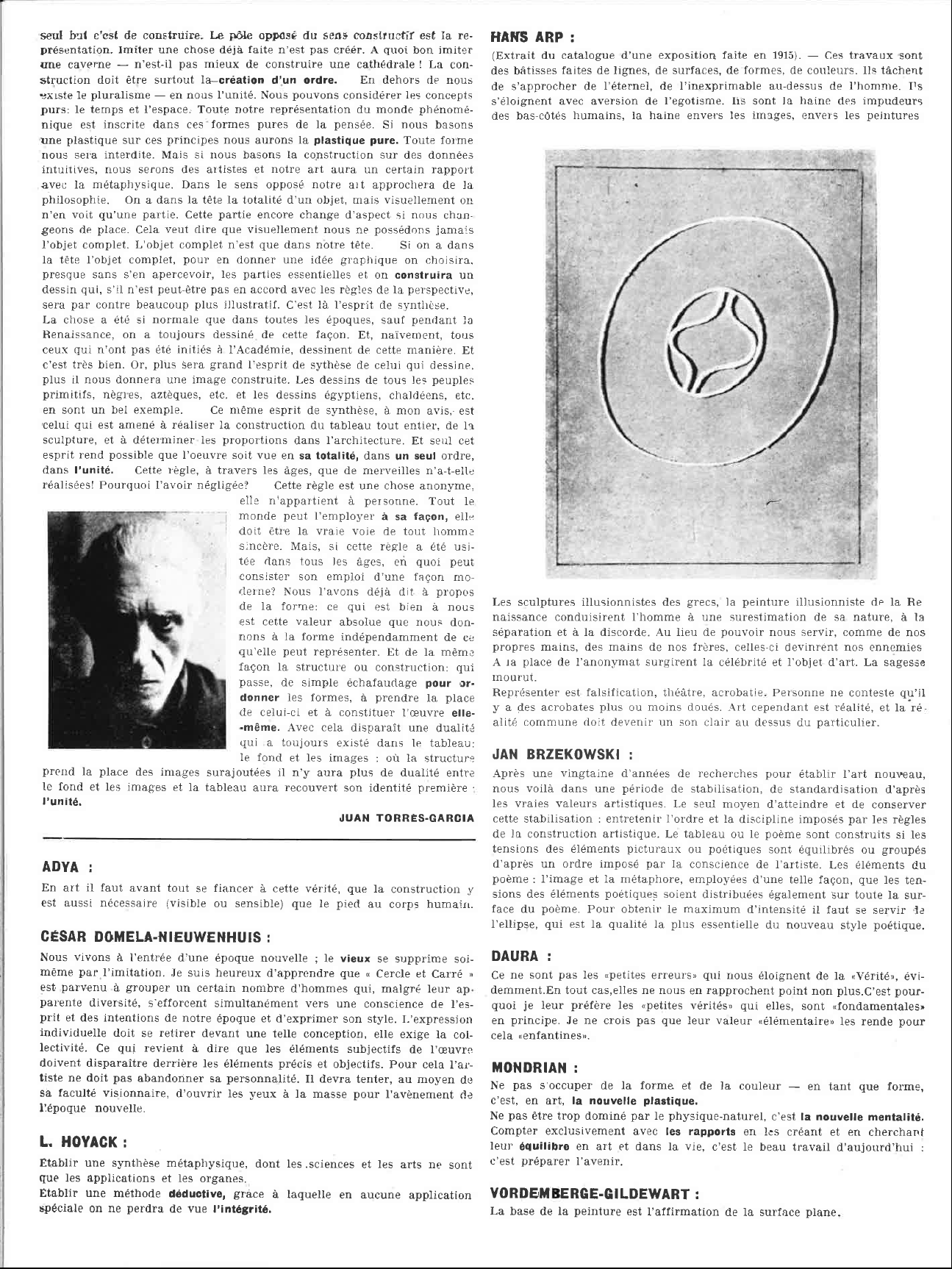

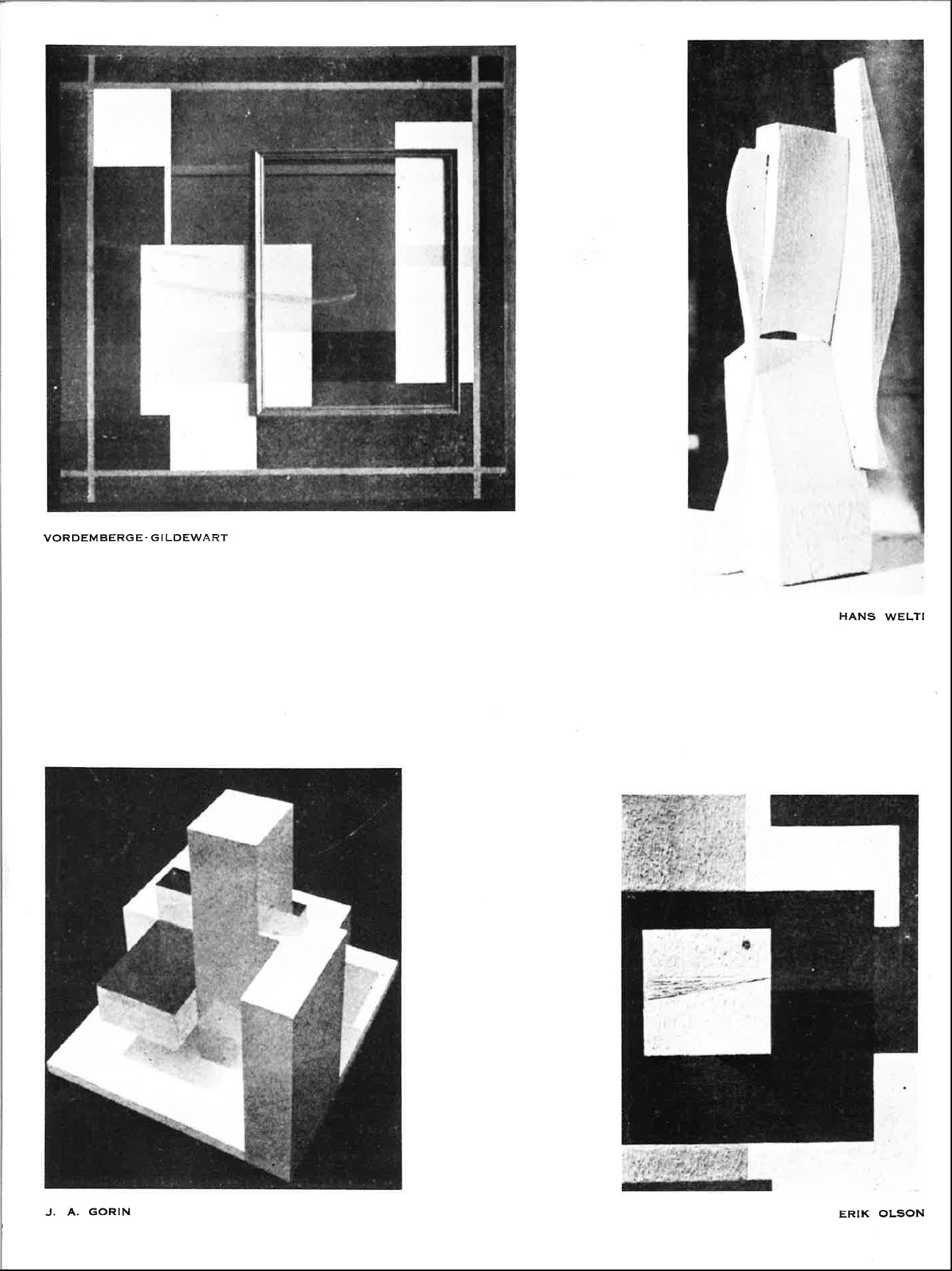

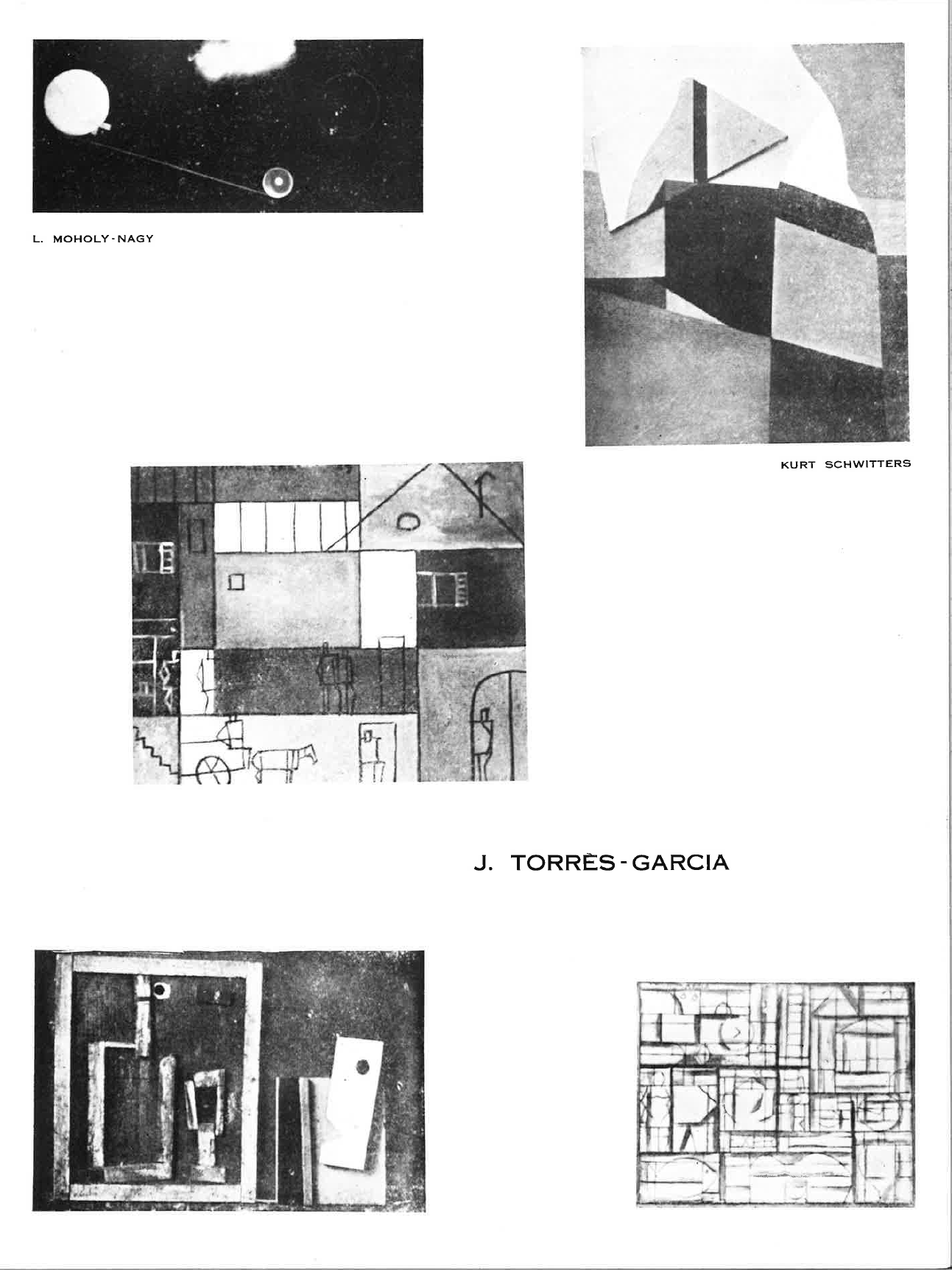

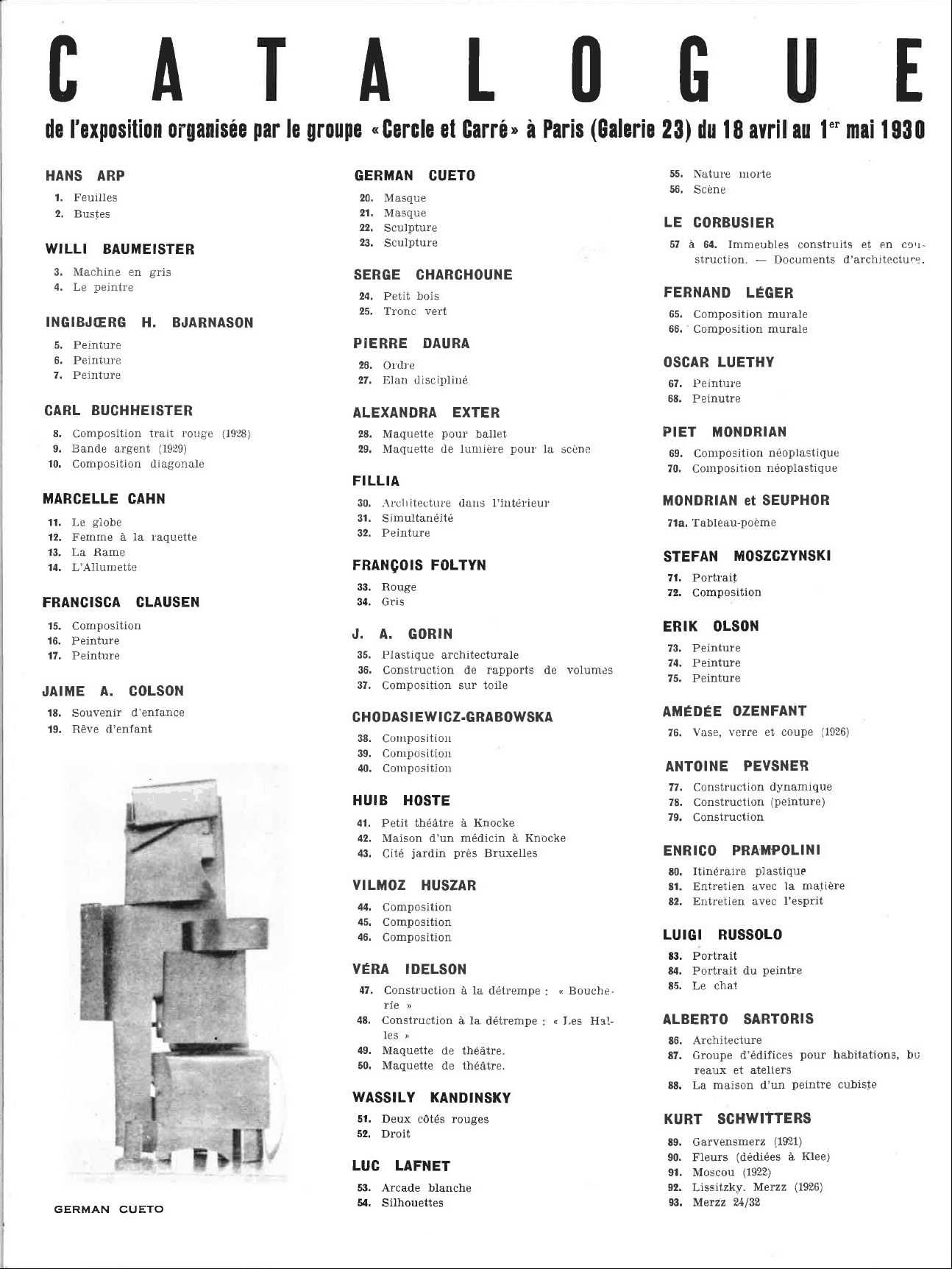

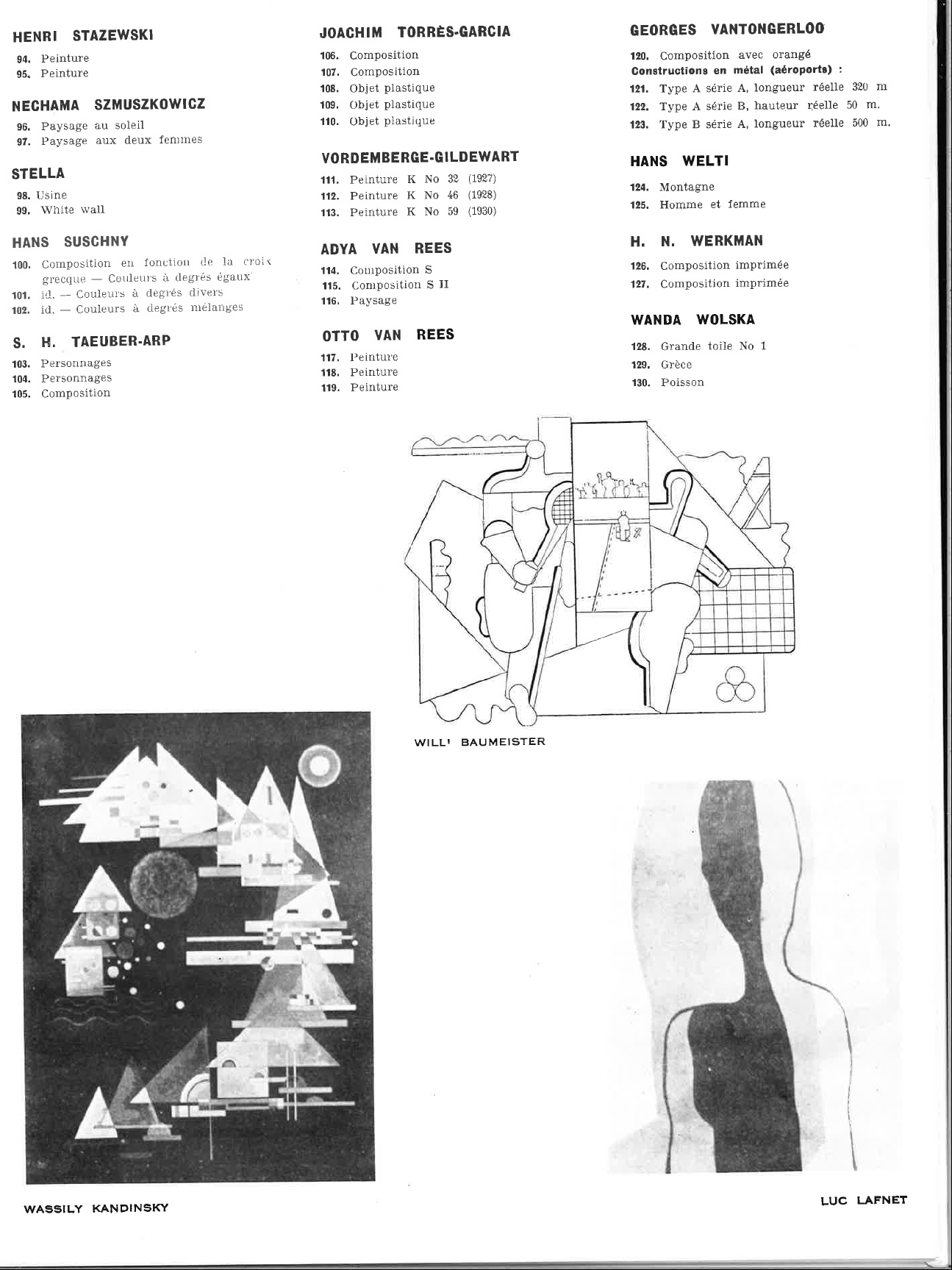

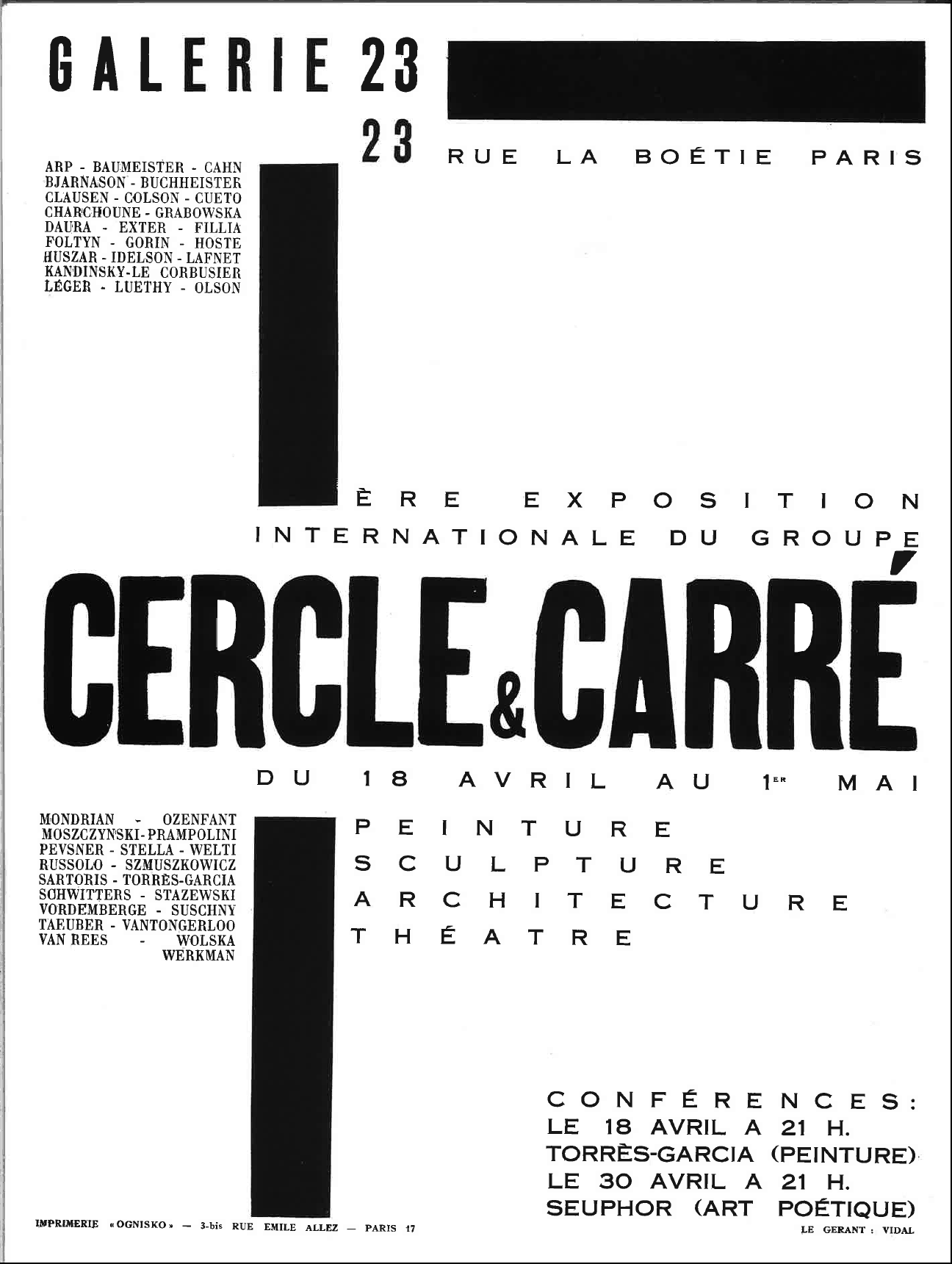

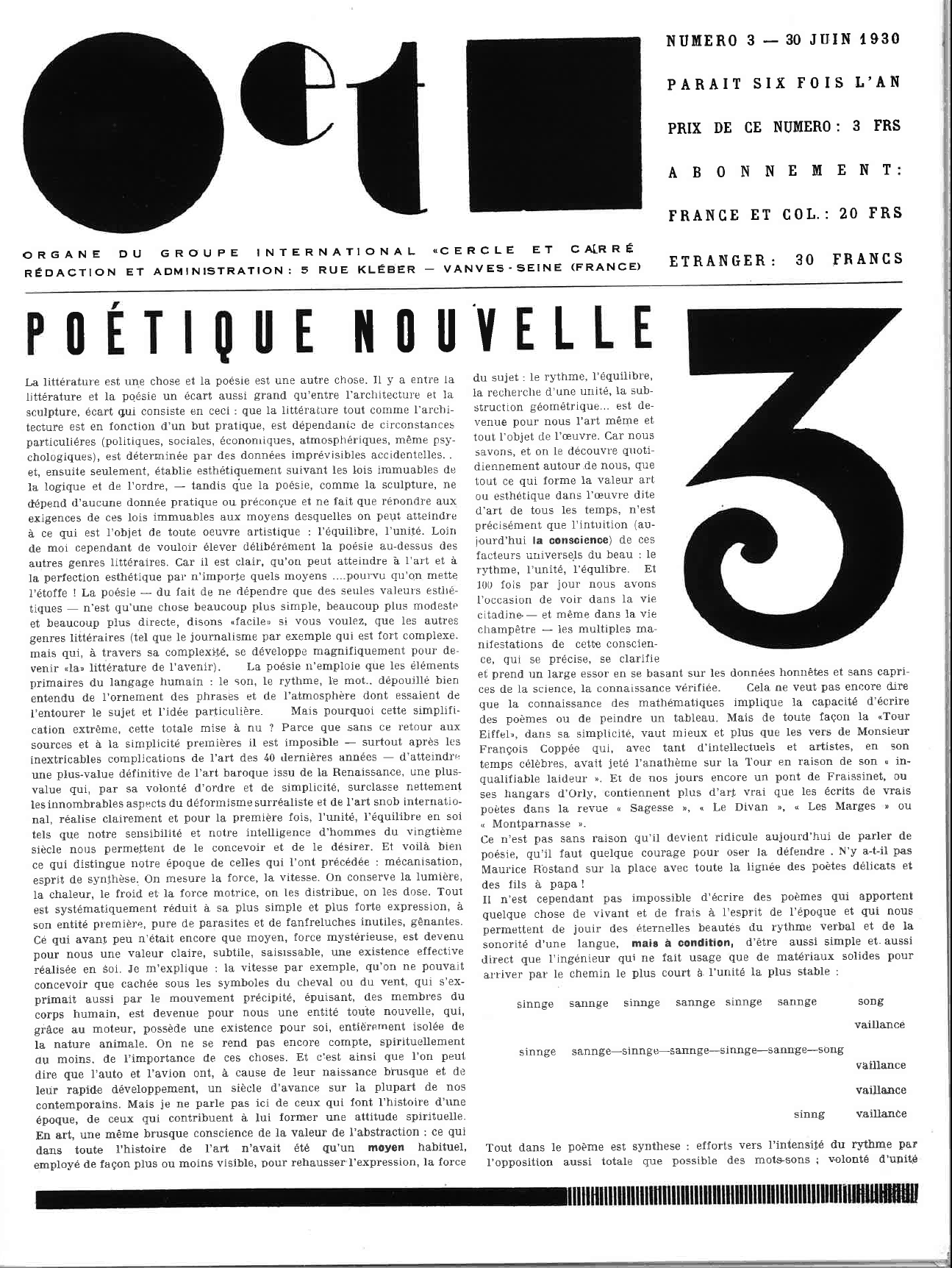

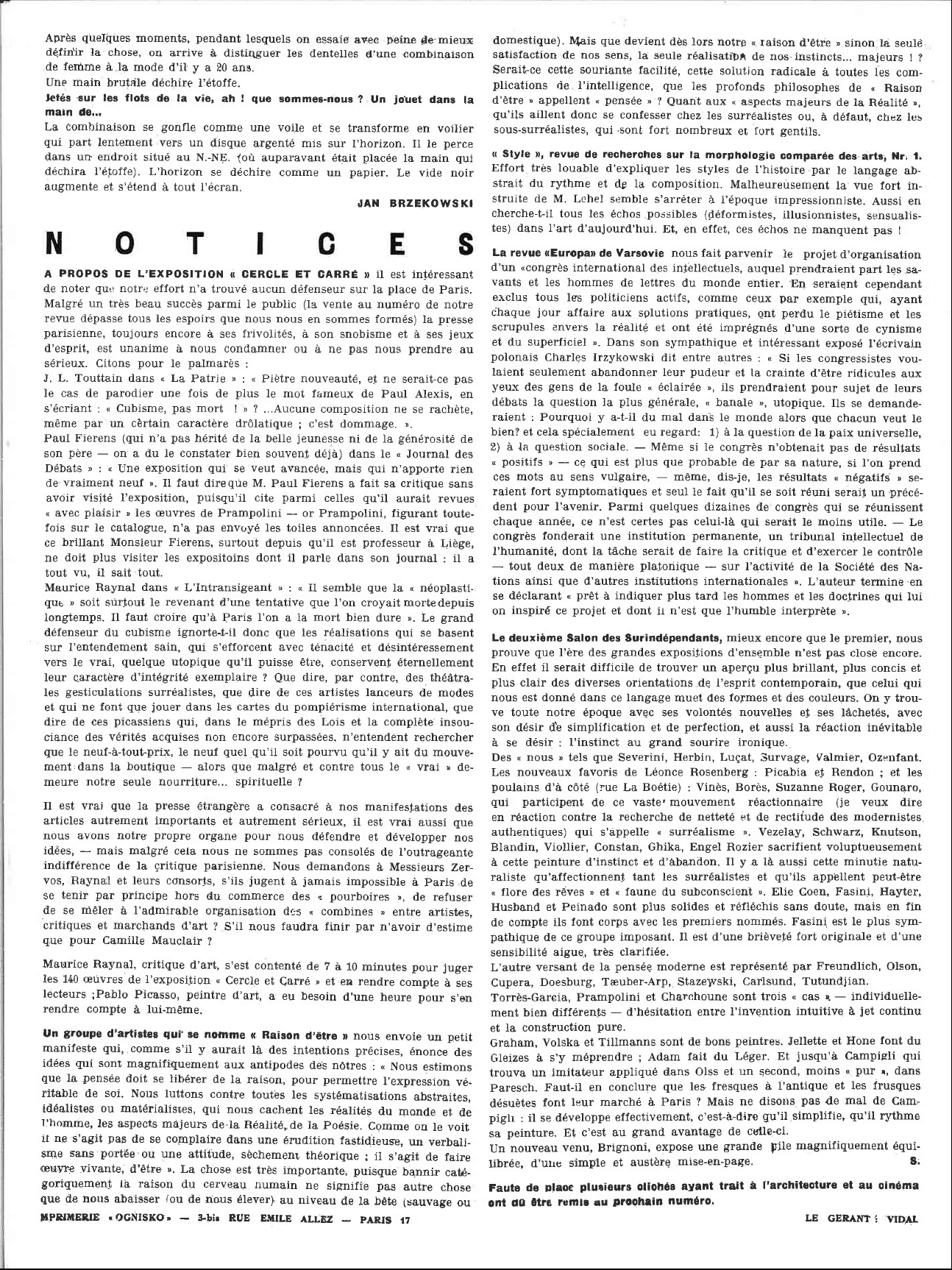

CERCLE ET CARRÉ

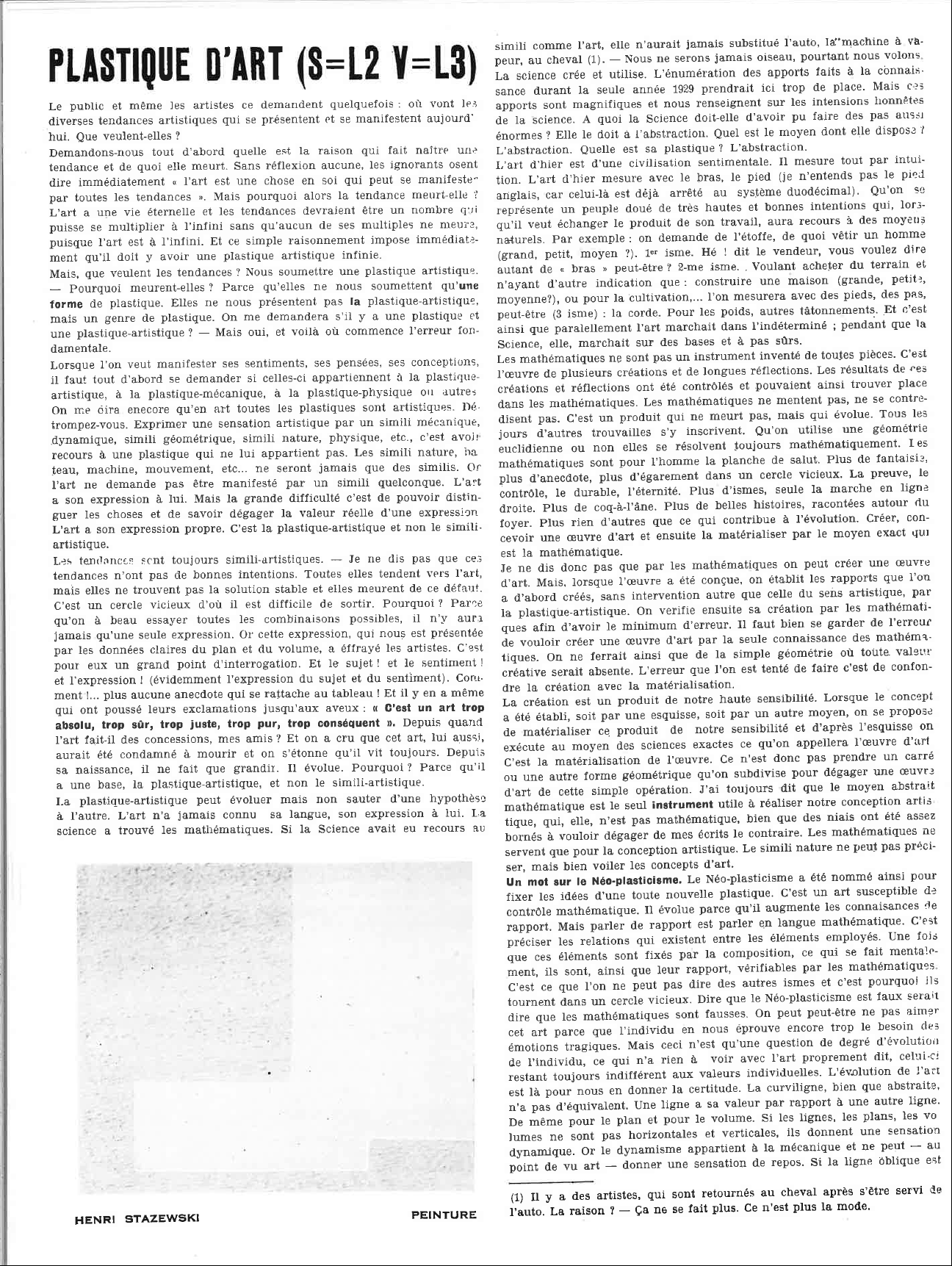

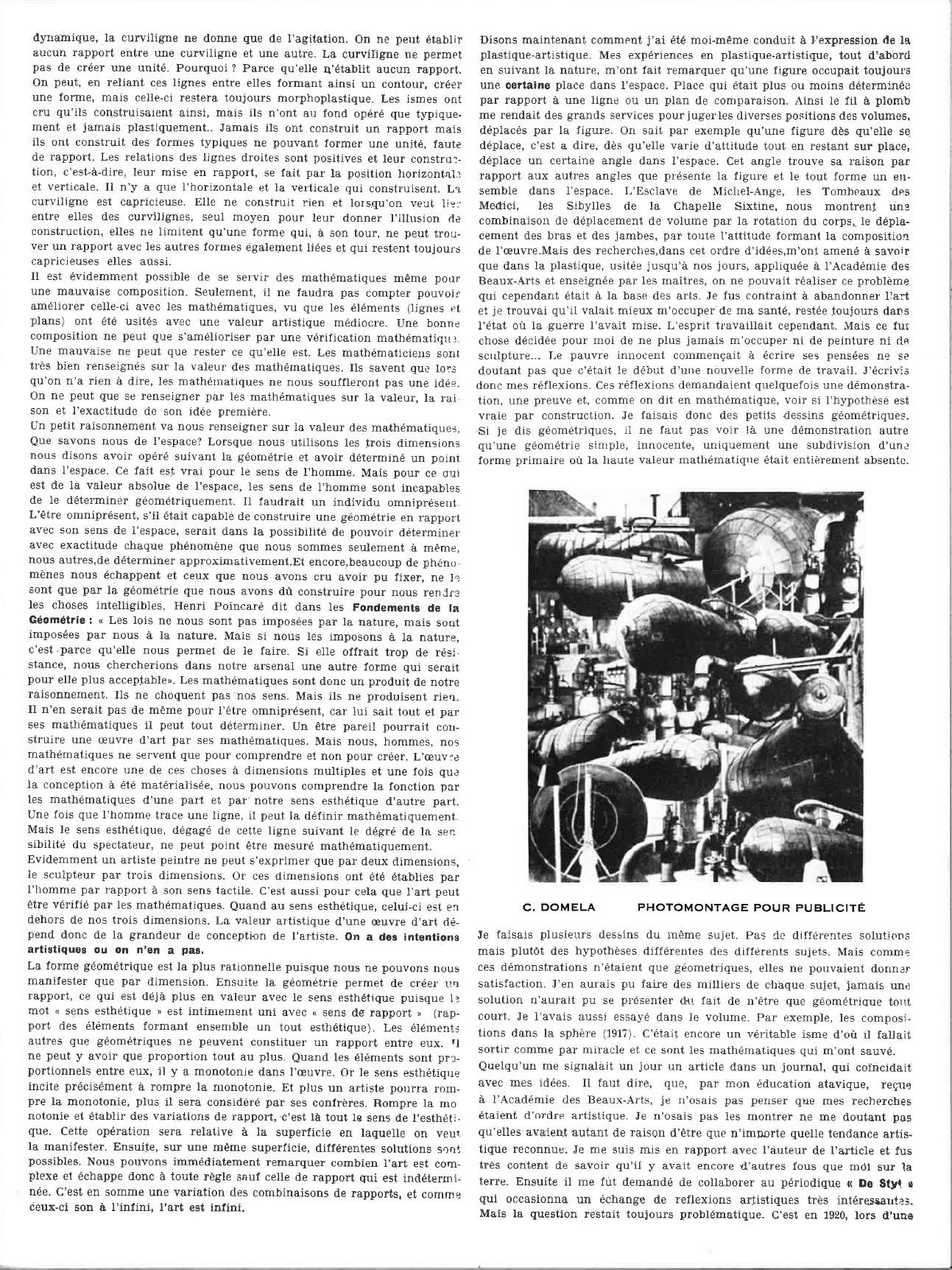

To understand the birth of the Cercle et Carré movement and its magazine, it is necessary to recall the Dada movement that dazzled Seuphor from his first meetings in Paris. The movement was in decline but much of its ideas and spirit remained. Seuphor considers it one of the major currents of the 20th century, one of the two cornerstones on which it was founded. The other is abstract art, which emerged from cubism, capable of erecting a completely new, non-figurative world. The ironic protest of dada sits next to it.

Jean Arp and his wife, Sophie Taeuber, were early Dadaists. They joined the small informal group that met every Sunday in the apartment that Seuphor occupied in the Paris region with his partner of the time, Ingeborg Bjarnasson. At first, the group was made up of Seuphor, Vantongerloo, Russolo and Mondrian, but it later included other artistic personalities such as Pevsner and his wife, Honneger, and the painter Joaquin Torrès-Garcia, who was the first to express the idea of making the group and its ideas visible, as opposed to those of Surrealism, which reigned in Paris under the rule of André Breton and the influence of psychoanalysis. The Cercle et Carré group grew with the arrival of Kandinsky, Baumeister, Moholy-Nagy etc. With about fifty members, it could not continue its meetings in the small two-room apartment of Vanves and established its meetings at the Café Voltaire, Place de l’Odéon. This is an astonishing coincidence for certain members, such as Arp and Sophie Taeuber, who were among the first Dadaists at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich! The group’s meetings were very animated. Seuphor proposed to concentrate on the idea of structure through the forms of the circle and the square and asked the painter Daura to improvise a logo. The logo was immediately approved by the members and the name Cercle et Carré was adopted as the name of the group and the title of the magazine through which it would express itself. Seuphor was appointed as director of the journal.

Cercle et Carré lasted only one year but the group was international and very active. It published three issues that are very successful. The third issue, with a print run of 1200 copies, was distributed in only two bookstores in Montparnasse and sold out in a few weeks.

In 1930, the group organized its first and only exhibition, which brought together a large number of artists, many of whom would become pillars of 20th century art: Gorin, Mondrian, Sophie Taeuber, Jean Arp, Le Corbusier, Schwitters, Fillia, and many others. Thanks to the contacts that Seuphor had established during his travels, and in particular at the Bauhaus, articles appeared in Europe, in Prague, in Poland… but in Paris, the exhibition only received two small press notices. For the artists, it was a fiasco. Internationalism was not in fashion in the xenophobic France of the interwar period, which only knew modern art through the surrealist movement.

An overflowing but poorly recognized activity as well as a cruel lack of money to feed himself undermined the health of Seuphor and triggered a pleurisy from which he nearly died. His friends collected means to send him to a sanatorium in Grasse, from which he emerged four months later, alive but profoundly transformed. In the meantime, Vantongerloo took advantage of the situation to get hold of his typewriter and all his contacts to found « Abstraction-Création» . Torrès-Garcia, who returned to Latin America with the title, presented himself there as the founder of the journal without ever mentioning Seuphor. All these events deeply affected Seuphor; he suddenly lost interest in modern art.

Sophie Berckelaers

Cercle et Carré told by Seuphor in Une vie a angle droit, 1988

Excerpt

« We had no premises to organize the group’s exhibitions. We needed money and we didn’t have any. Nobody was rich, far from it. We had established a membership fee and the members of Cercle et Carré had to pay 25 Fr. per month. There were two monthly meetings in a Parisian café. There were between 20 and 30 people each time, all artists. I was the only writer. I was making large gouaches at the time, but I didn’t consider myself a painter. I was the poet of the group and the writer, the translator, the Dolmetscher (interpreter). We went to visit a large hall on rue La Boétie and prepared a handwritten contract, signed by Vantongerloo, Luigi Russolo, Torres-Garcia and myself. The group decided that there would be a Cercle et Carré publication and that I would be the director in charge. The meetings were always epic, because everyone was talking at the same time. The group meetings were pure uproar from beginning to end. Nothing could come out. Everyone wanted to talk, some very loudly. Vantongerloo had theories. Pevsner defended dogmas. Mondrian did not speak. Torres-Garcia was trying, but he spoke very bad French. I didn’t interfere. When it was over, I would tell myself: « they came, they always come» . In fact, fifteen days later, they were all there again. I wrote the minutes of these meetings. I wrote what I wanted, because in the tumult one said one thing, the other another. I did it my way. It was actually my peaceful nature, my flexibility and my decision to do everything my way that saved the movement.

The name of the group came from me. Since I was young I was lulled by the idea of circle and square, yin and yang, heaven and earth, the Yi-king. I proposed this as a summary, easy to approach. They all agreed, whereas before we had been arguing hard about a title. I had proposed the idea of structure, figurative or not, but essentially structure. This in opposition to surrealism, which was only literary, psychoanalytical. But structure did not rally the majority either. One day, I asked Daura, one of the members who made very beautiful drawings, to compose a vignette. He drew one that delighted everyone. The magazine and the group were founded on that. Unfortunately, it didn’t last long. The first meetings were held at the Café Voltaire, Place de l’Odéon around November 1929. The exhibition took place in April 1930. It brought together Arp, Schwitters, Mondrian, Kandinsky, Baumeister, Gorin, Huszar, Le Corbusier, Léger, Ozenfant, Pevsner, Vordemberge-Gildewart, Sophie Taeuber, Marcel Cahn, Werkman, Vantongerloo, and others.

There was a first issue on March 15. Then two more after the exhibition. I fell ill while preparing the fourth issue. Everything fell apart. I was suffering from pleurisy. I had to stay in bed for two months and the doctor ordered me to go to the South for convalescence. My friends contributed to pay for my stay in Grasse. I spent four months among tuberculosis patients. Every day I was in contact with death. This should have led to my death, but I came out of it. Because the city of Grasse refused sanatoriums on its territory, the hotels were clandestine sanatoriums. You were not supposed to die there. The dead were picked up at night, silently, as if nothing had happened. I had lunch and dinner with delicious young people who did not reappear at breakfast the next day. They were gone forever…. »

Seuphor tells the end of the movement in Un siècle de liberté. 1996

Excerpt

« Four months later, the doctor who was treating me, a great specialist in tuberculosis, advised me to return to Paris. With the summer coming, he thought I would be less in danger than on the Côte d’Azur. So I came home to find that my apartment had been given to someone else by my Icelandic friend. She had left, taking everything I owned with her! Moreover, she had given all the documents concerning Cercle et Carré to Vantongerloo, who had taken advantage of the situation to create a new movement, Abstraction-Création -which did not yet have that name-, with all the documents taken from my place! There, a profound mutation took place. What I had lived and experienced in Grasse, this theft of my things – especially my typewriter – disgusted me from everything and led me to suddenly lose interest in modern art (…)

I then went to see my printer friends, exquisite Polish Jews, brothers and sister, the Mitskouns, where the magazine Cercle et Carré was printed. Seeing me in great need, they immediately offered me a job as a proofreader and, above all, as director of the French part of their activities. They treated me as if I were their child. They knew that, after leaving the sanatorium, I was in danger of relapsing. The only solution: I had to eat, especially meat. So, every day, I went to their house, in Courbevoie, where a Polish cordon-bleu woman was waiting for me and she prepared not a meal, but a feast, and they forced me to eat. It was really exquisite. They saved my life. They were goodness itself. So they did not come back from the concentration camps. They were people with a lot of culture and especially with a passion for metaphysics. They always wanted to talk to me for hours, and the work was not done. I was paid and fed… to talk! A real family.»

↑

Excerpt from:

Michel Seuphor, un siècle de libertés

CERCLE ET CARRÉ

To understand the birth of the Cercle et Carré movement and its magazine, it is necessary to recall the Dada movement that dazzled Seuphor from his first meetings in Paris. The movement was in decline but much of its ideas and spirit remained. Seuphor considers it one of the major currents of the 20th century, one of the two cornerstones on which it was founded. The other is abstract art, which emerged from cubism, capable of erecting a completely new, non-figurative world. The ironic protest of dada sits next to it.

Jean Arp and his wife, Sophie Taeuber, were early Dadaists. They joined the small informal group that met every Sunday in the apartment that Seuphor occupied in the Paris region with his partner of the time, Ingeborg Bjarnasson. At first, the group was made up of Seuphor, Vantongerloo, Russolo and Mondrian, but it later included other artistic personalities such as Pevsner and his wife, Honneger, and the painter Joaquin Torrès-Garcia, who was the first to express the idea of making the group and its ideas visible, as opposed to those of Surrealism, which reigned in Paris under the rule of André Breton and the influence of psychoanalysis. The Cercle et Carré group grew with the arrival of Kandinsky, Baumeister, Moholy-Nagy etc. With about fifty members, it could not continue its meetings in the small two-room apartment of Vanves and established its meetings at the Café Voltaire, Place de l’Odéon. This is an astonishing coincidence for certain members, such as Arp and Sophie Taeuber, who were among the first Dadaists at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich! The group’s meetings were very animated. Seuphor proposed to concentrate on the idea of structure through the forms of the circle and the square and asked the painter Daura to improvise a logo. The logo was immediately approved by the members and the name Cercle et Carré was adopted as the name of the group and the title of the magazine through which it would express itself. Seuphor was appointed as director of the journal.

Cercle et Carré lasted only one year but the group was international and very active. It published three issues that are very successful. The third issue, with a print run of 1200 copies, was distributed in only two bookstores in Montparnasse and sold out in a few weeks.

In 1930, the group organized its first and only exhibition, which brought together a large number of artists, many of whom would become pillars of 20th century art: Gorin, Mondrian, Sophie Taeuber, Jean Arp, Le Corbusier, Schwitters, Fillia, and many others. Thanks to the contacts that Seuphor had established during his travels, and in particular at the Bauhaus, articles appeared in Europe, in Prague, in Poland… but in Paris, the exhibition only received two small press notices. For the artists, it was a fiasco. Internationalism was not in fashion in the xenophobic France of the interwar period, which only knew modern art through the surrealist movement.

An overflowing but poorly recognized activity as well as a cruel lack of money to feed himself undermined the health of Seuphor and triggered a pleurisy from which he nearly died. His friends collected means to send him to a sanatorium in Grasse, from which he emerged four months later, alive but profoundly transformed. In the meantime, Vantongerloo took advantage of the situation to get hold of his typewriter and all his contacts to found « Abstraction-Création» . Torrès-Garcia, who returned to Latin America with the title, presented himself there as the founder of the journal without ever mentioning Seuphor. All these events deeply affected Seuphor; he suddenly lost interest in modern art.

Sophie Berckelaers

Cercle et Carré told by Seuphor in Une vie a angle droit, 1988

Excerpt

« We had no premises to organize the group’s exhibitions. We needed money and we didn’t have any. Nobody was rich, far from it. We had established a membership fee and the members of Cercle et Carré had to pay 25 Fr. per month. There were two monthly meetings in a Parisian café. There were between 20 and 30 people each time, all artists. I was the only writer. I was making large gouaches at the time, but I didn’t consider myself a painter. I was the poet of the group and the writer, the translator, the Dolmetscher (interpreter). We went to visit a large hall on rue La Boétie and prepared a handwritten contract, signed by Vantongerloo, Luigi Russolo, Torres-Garcia and myself. The group decided that there would be a Cercle et Carré publication and that I would be the director in charge. The meetings were always epic, because everyone was talking at the same time. The group meetings were pure uproar from beginning to end. Nothing could come out. Everyone wanted to talk, some very loudly. Vantongerloo had theories. Pevsner defended dogmas. Mondrian did not speak. Torres-Garcia was trying, but he spoke very bad French. I didn’t interfere. When it was over, I would tell myself: « they came, they always come» . In fact, fifteen days later, they were all there again. I wrote the minutes of these meetings. I wrote what I wanted, because in the tumult one said one thing, the other another. I did it my way. It was actually my peaceful nature, my flexibility and my decision to do everything my way that saved the movement.

The name of the group came from me. Since I was young I was lulled by the idea of circle and square, yin and yang, heaven and earth, the Yi-king. I proposed this as a summary, easy to approach. They all agreed, whereas before we had been arguing hard about a title. I had proposed the idea of structure, figurative or not, but essentially structure. This in opposition to surrealism, which was only literary, psychoanalytical. But structure did not rally the majority either. One day, I asked Daura, one of the members who made very beautiful drawings, to compose a vignette. He drew one that delighted everyone. The magazine and the group were founded on that. Unfortunately, it didn’t last long. The first meetings were held at the Café Voltaire, Place de l’Odéon around November 1929. The exhibition took place in April 1930. It brought together Arp, Schwitters, Mondrian, Kandinsky, Baumeister, Gorin, Huszar, Le Corbusier, Léger, Ozenfant, Pevsner, Vordemberge-Gildewart, Sophie Taeuber, Marcel Cahn, Werkman, Vantongerloo, and others.

There was a first issue on March 15. Then two more after the exhibition. I fell ill while preparing the fourth issue. Everything fell apart. I was suffering from pleurisy. I had to stay in bed for two months and the doctor ordered me to go to the South for convalescence. My friends contributed to pay for my stay in Grasse. I spent four months among tuberculosis patients. Every day I was in contact with death. This should have led to my death, but I came out of it. Because the city of Grasse refused sanatoriums on its territory, the hotels were clandestine sanatoriums. You were not supposed to die there. The dead were picked up at night, silently, as if nothing had happened. I had lunch and dinner with delicious young people who did not reappear at breakfast the next day. They were gone forever…. »

Seuphor tells the end of the movement in Un siècle de liberté. 1996

Excerpt

« Four months later, the doctor who was treating me, a great specialist in tuberculosis, advised me to return to Paris. With the summer coming, he thought I would be less in danger than on the Côte d’Azur. So I came home to find that my apartment had been given to someone else by my Icelandic friend. She had left, taking everything I owned with her! Moreover, she had given all the documents concerning Cercle et Carré to Vantongerloo, who had taken advantage of the situation to create a new movement, Abstraction-Création -which did not yet have that name-, with all the documents taken from my place! There, a profound mutation took place. What I had lived and experienced in Grasse, this theft of my things – especially my typewriter – disgusted me from everything and led me to suddenly lose interest in modern art (…)

I then went to see my printer friends, exquisite Polish Jews, brothers and sister, the Mitskouns, where the magazine Cercle et Carré was printed. Seeing me in great need, they immediately offered me a job as a proofreader and, above all, as director of the French part of their activities. They treated me as if I were their child. They knew that, after leaving the sanatorium, I was in danger of relapsing. The only solution: I had to eat, especially meat. So, every day, I went to their house, in Courbevoie, where a Polish cordon-bleu woman was waiting for me and she prepared not a meal, but a feast, and they forced me to eat. It was really exquisite. They saved my life. They were goodness itself. So they did not come back from the concentration camps. They were people with a lot of culture and especially with a passion for metaphysics. They always wanted to talk to me for hours, and the work was not done. I was paid and fed… to talk! A real family.»

↑

Excerpt from:

Michel Seuphor, un siècle de libertés

•

1930, un diner au restaurant Voltaire. De gauche à droite R.Delaunay, Arp, Stazewsky, debout Giacelli, Florence Henri, Seuphor, Brzekowski, Pouma, Vantongerloo, Les Werner, S Taeuber, Mondrian, S.Delaunay

•

Chez Paul Dermée à Paris, 9 Juin 1928. De gauche à droite : Debout : Michel Seuphor, Piet Mondrian, Georges Vantongerloo, Luigi Ruissolo, Ilarie Voronca, Paul Dermée, Tysliava. Assis : Céline Arnaud, Rafalowski, Henri Stazewski.

•

« Cercle et Carré »

dans le sous sol de la galerie 23. Au premier plan, à gauche, Antoine Pevsner, accroupis à côté du tonneau : Michel Seuphor, et près de lui, baissé, Hans Arp.↑

Cercle et carré

n° 1

↑

Cercle et carré

n°2

↑

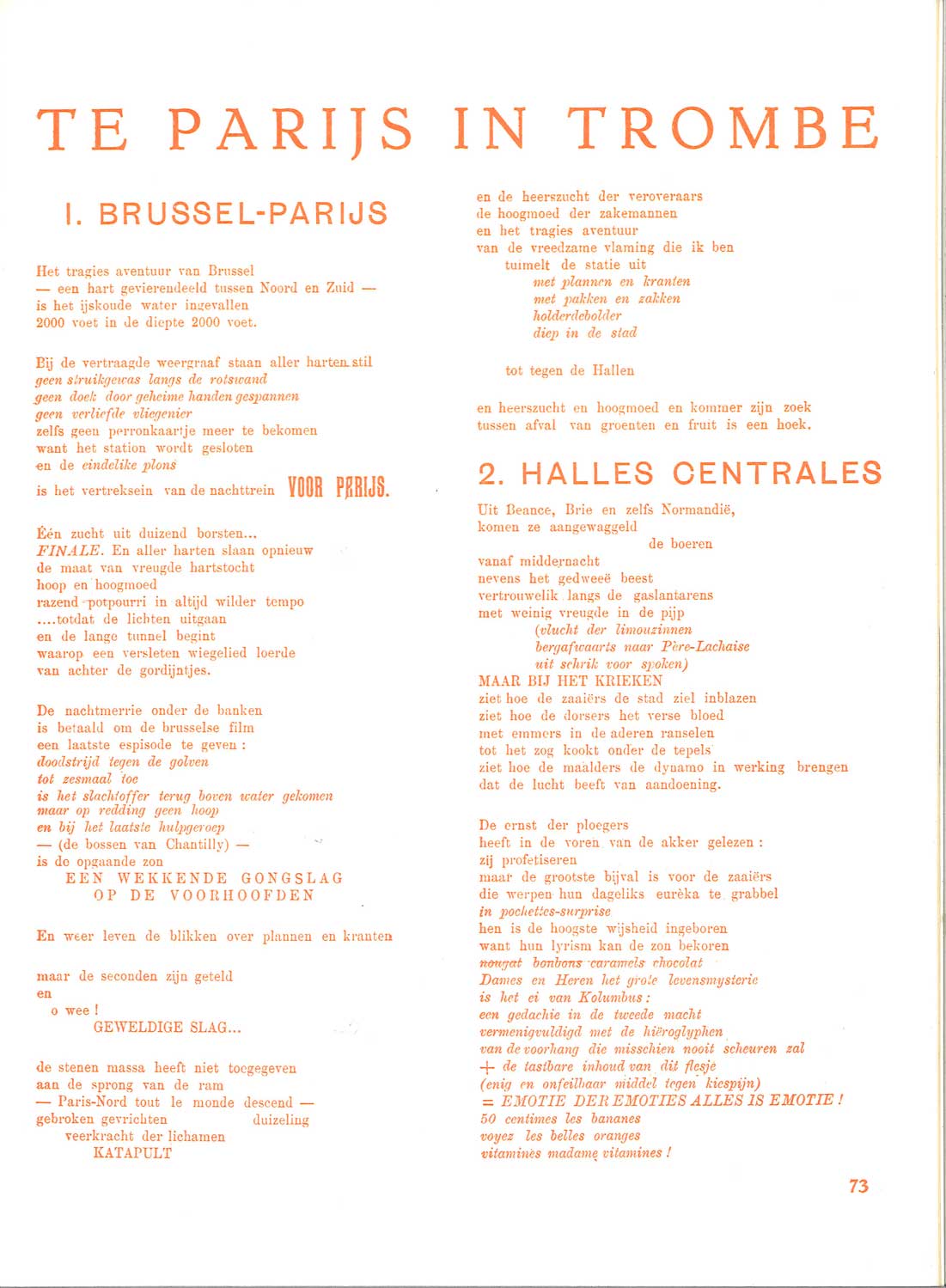

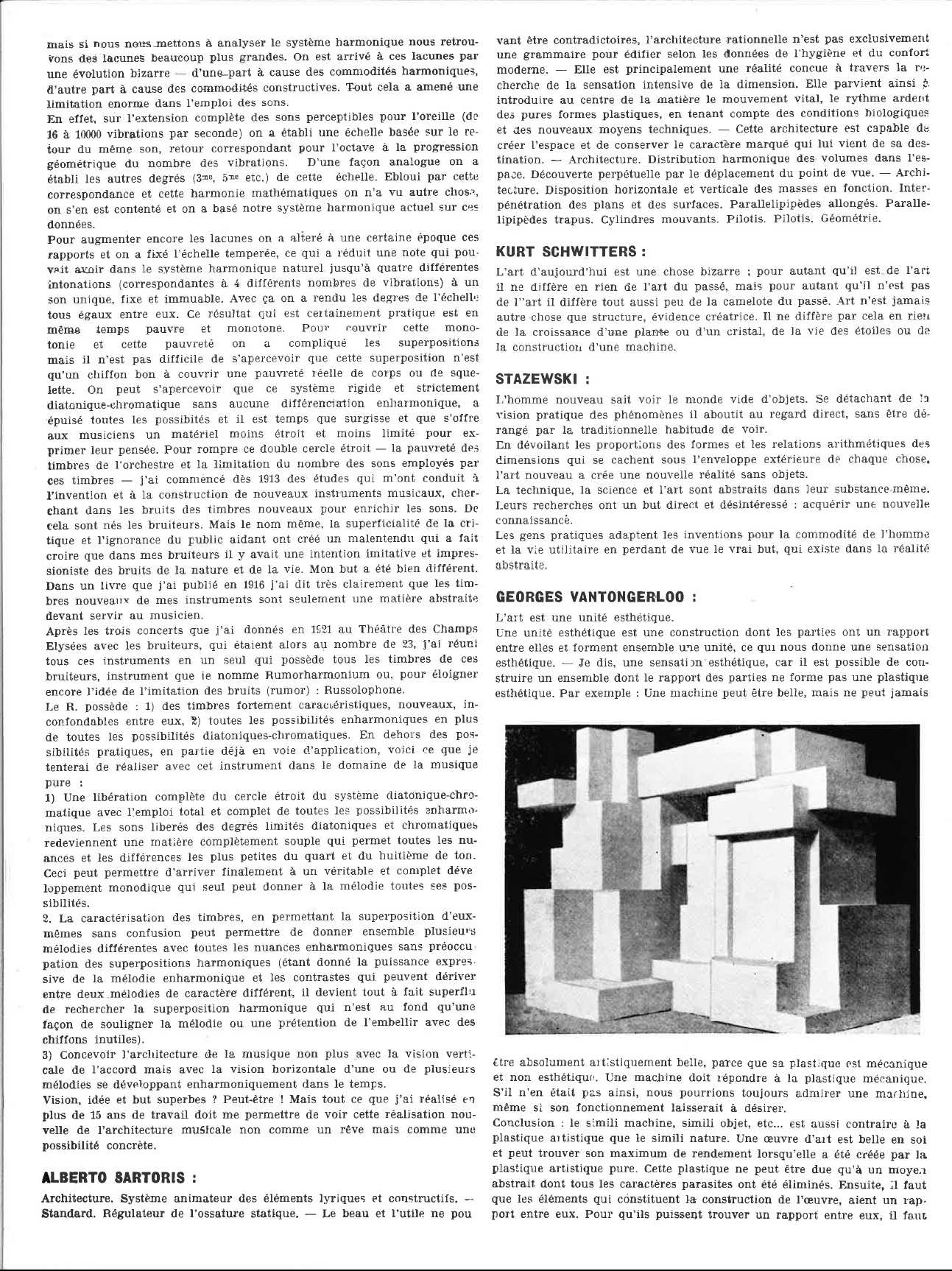

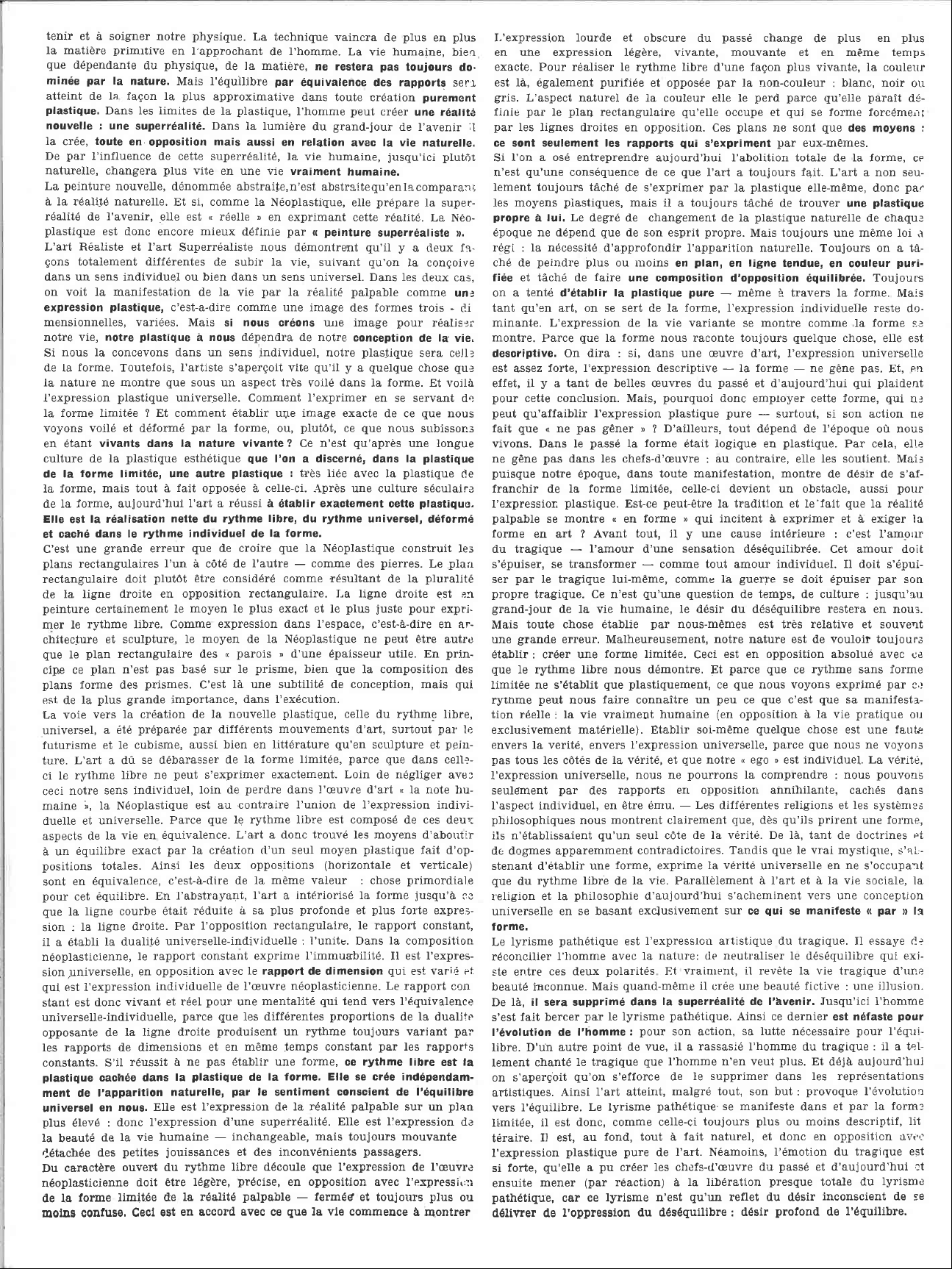

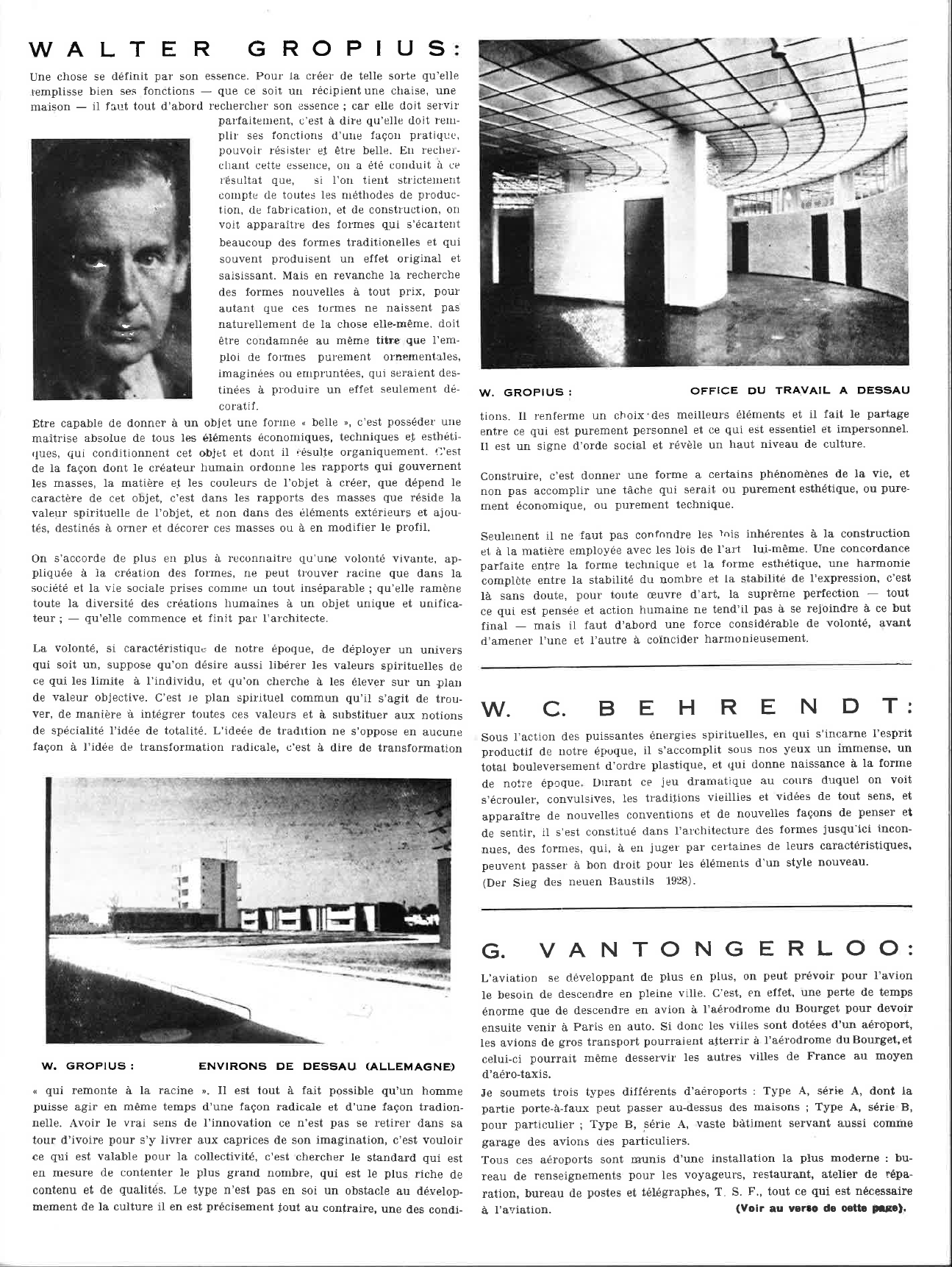

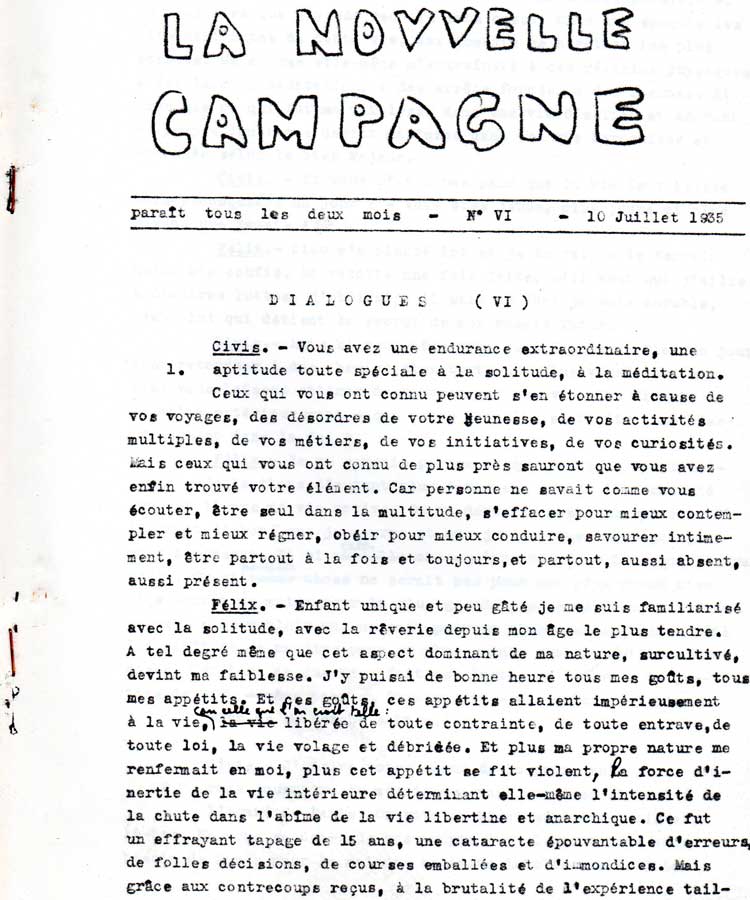

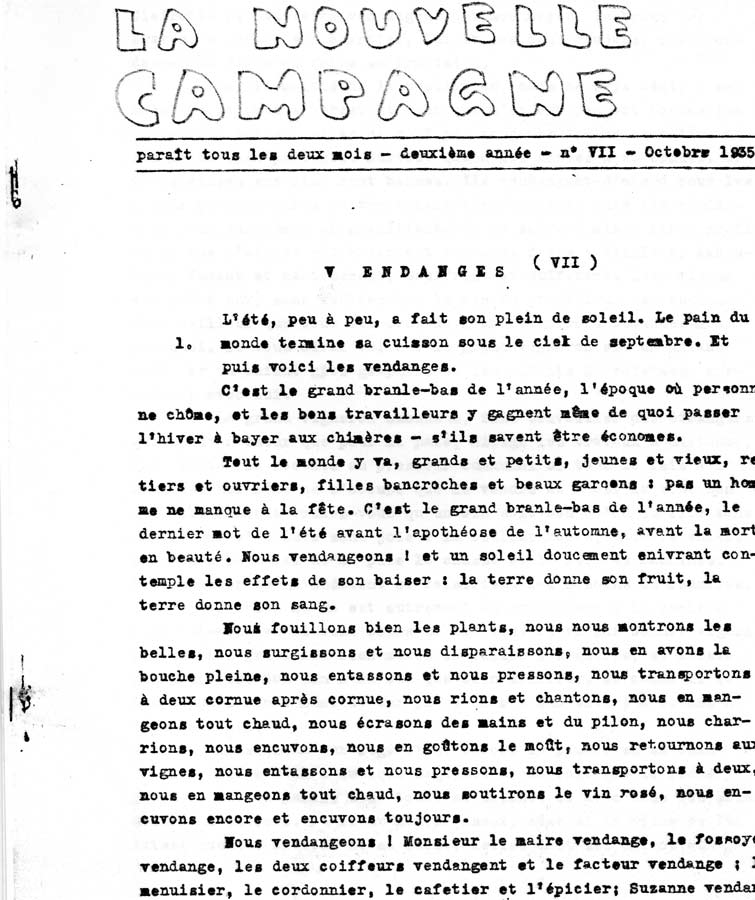

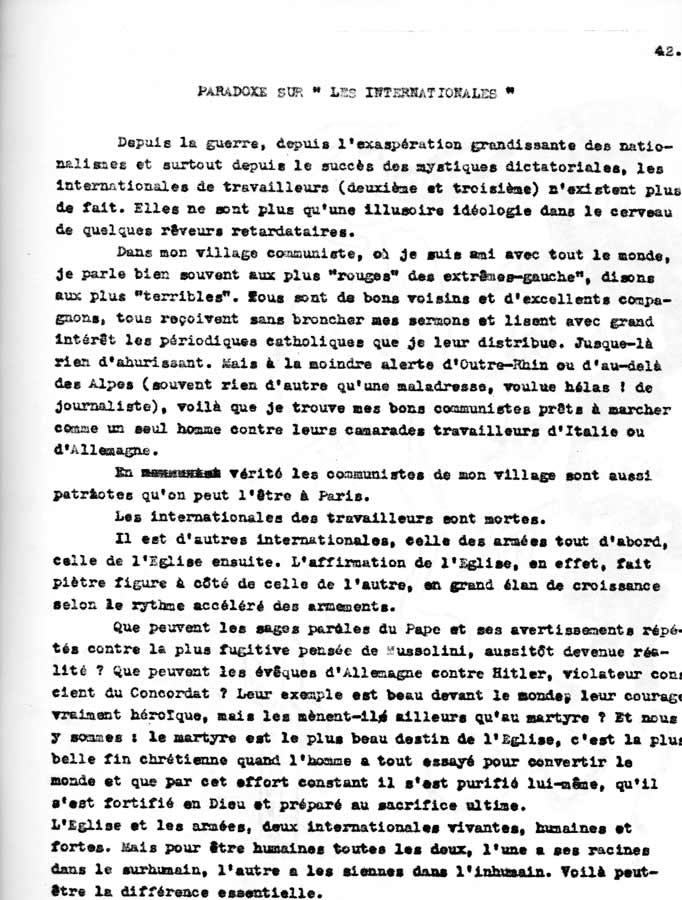

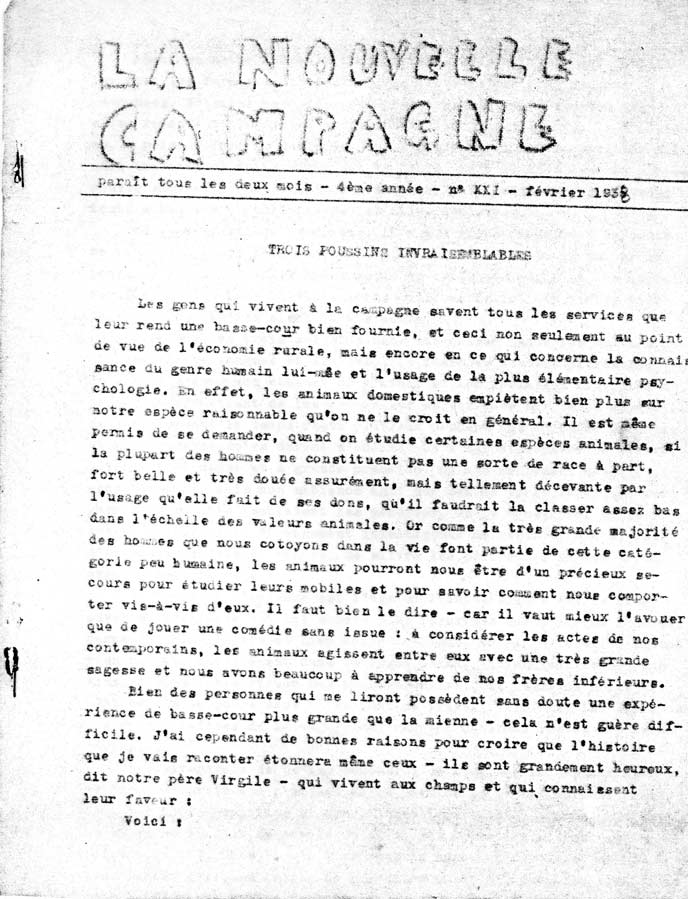

La Nouvelle Campagne

n° VI, juillet 1935

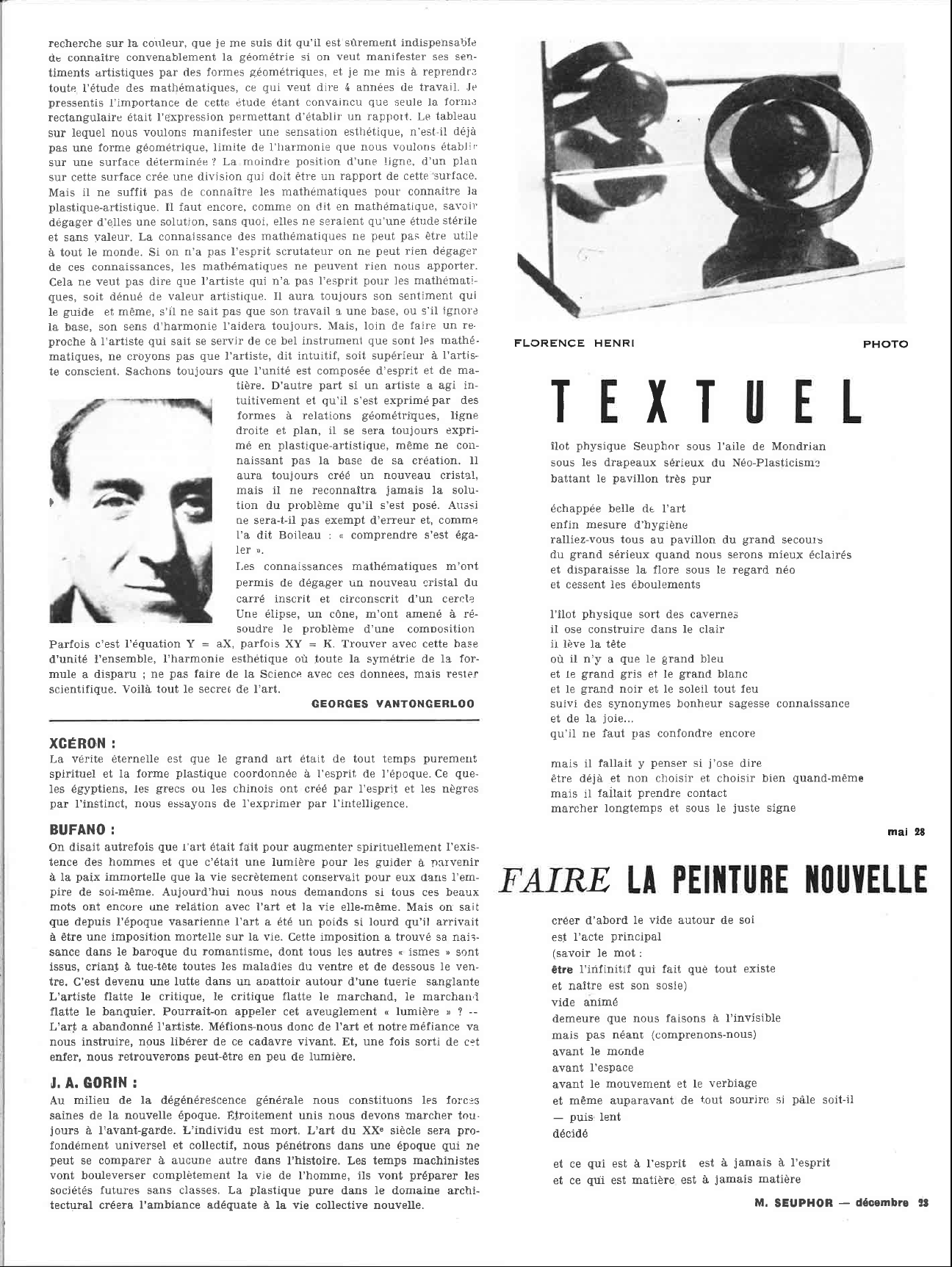

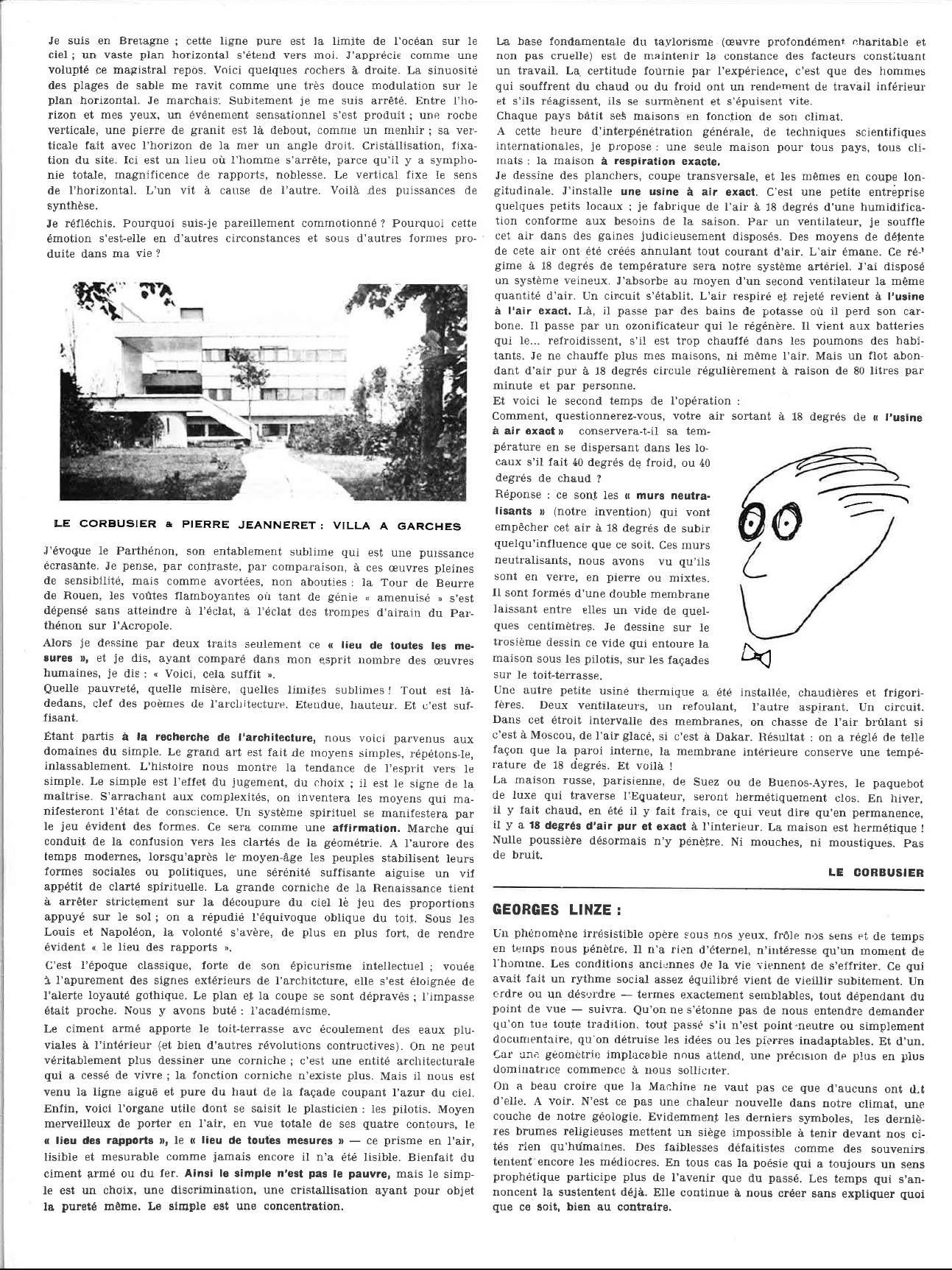

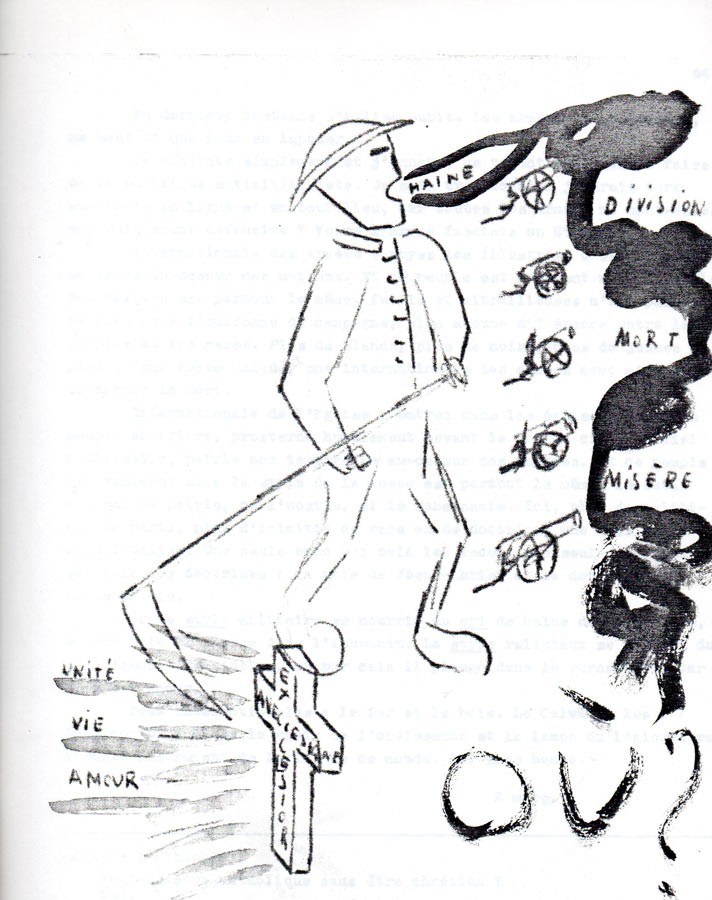

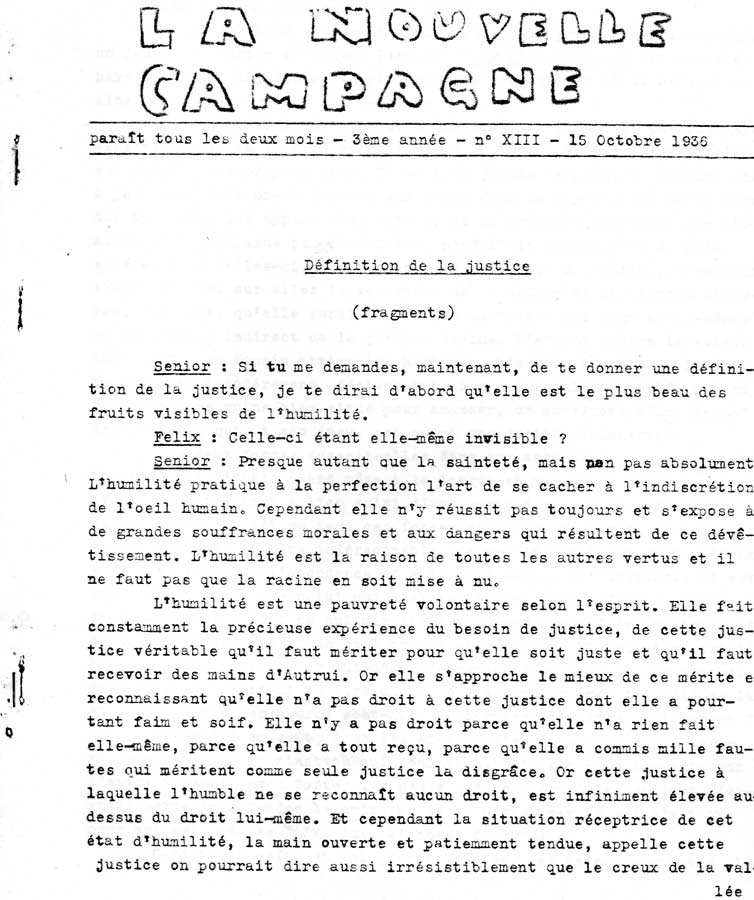

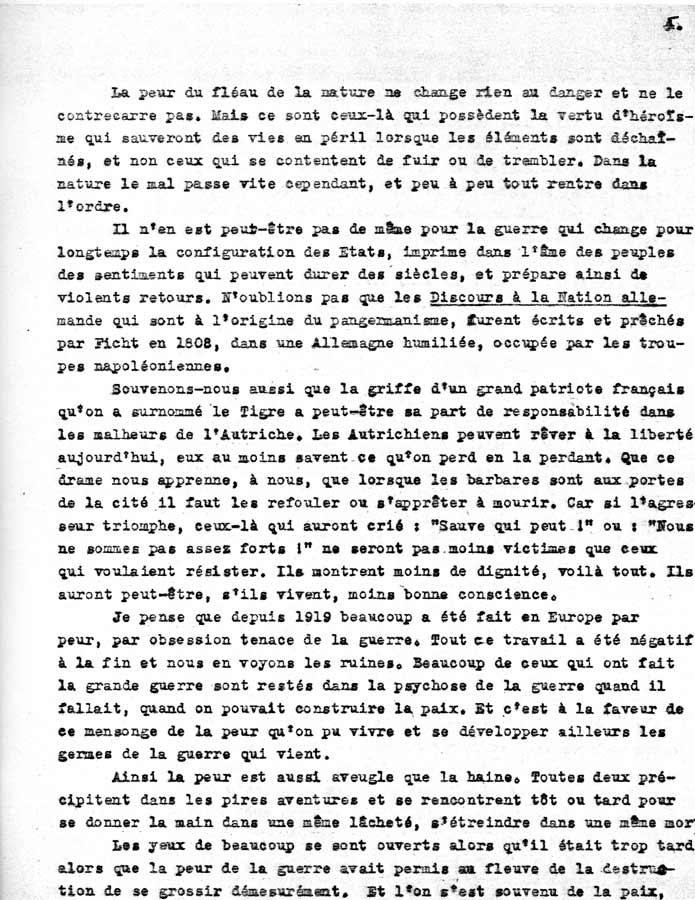

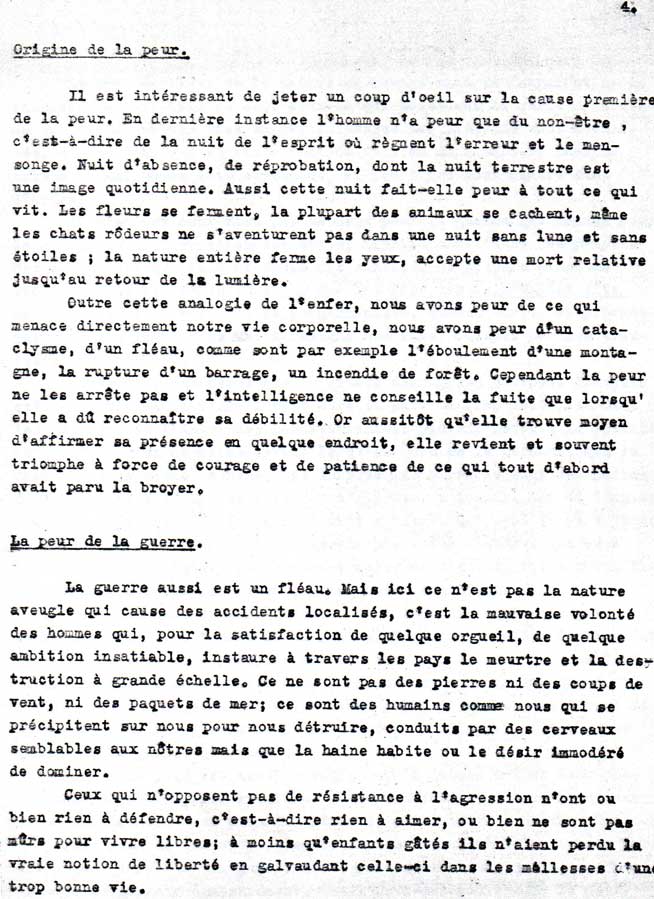

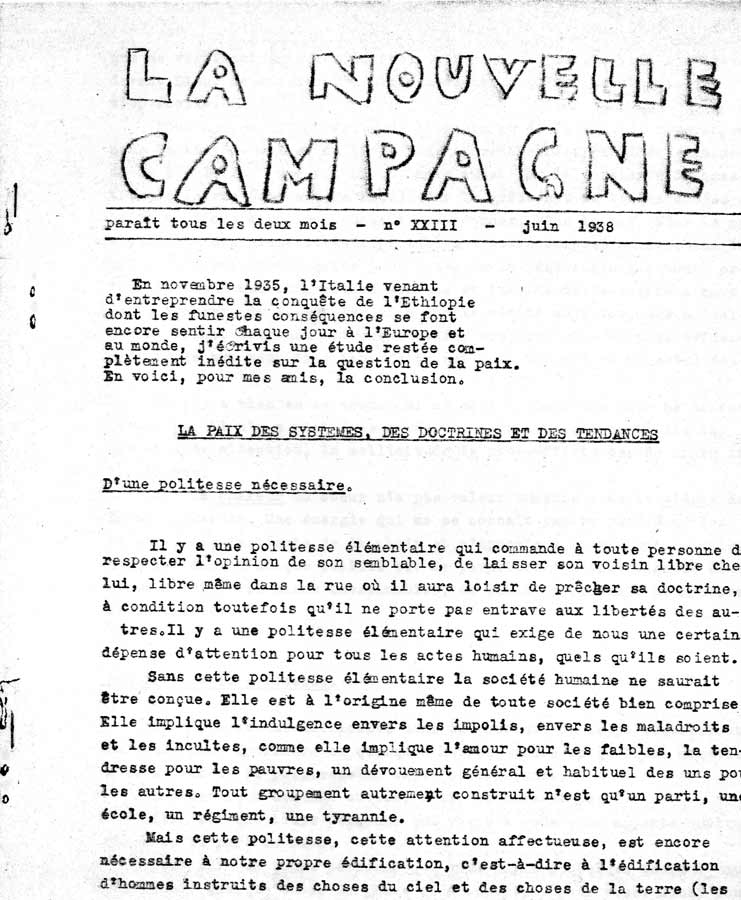

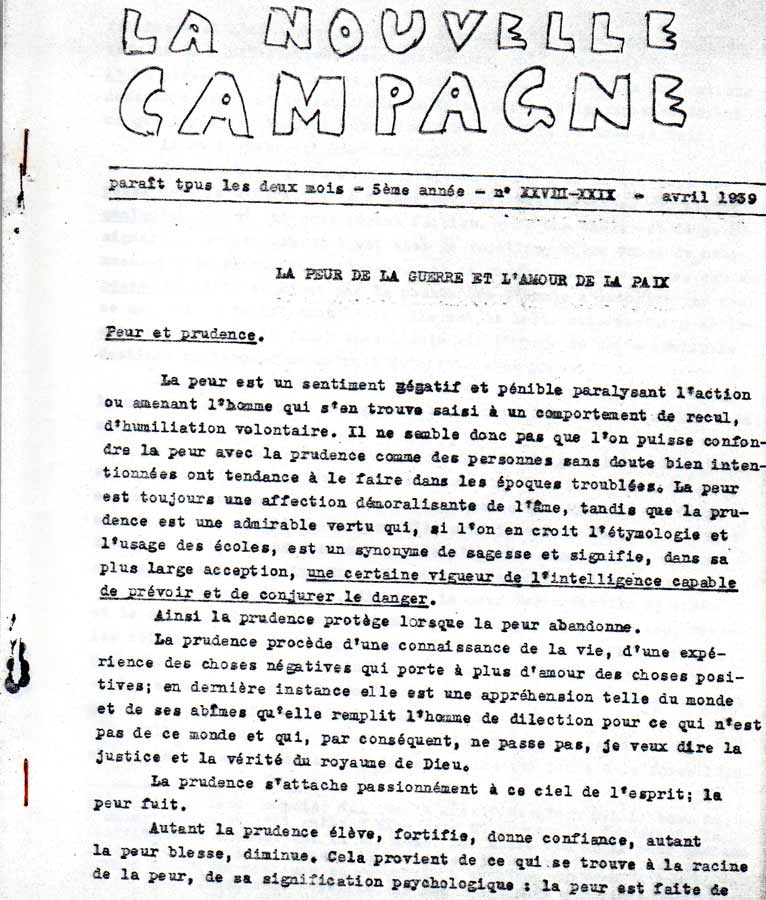

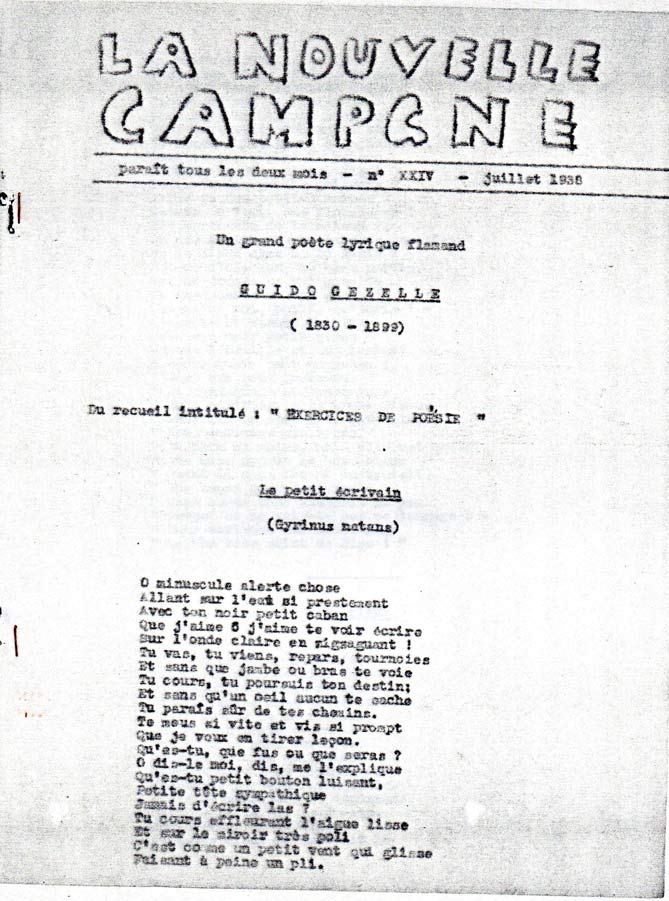

LA NOUVELLE CAMPAGNE

In 1934, Michel Seuphor, through the intermediary of Jacques Maritain, came in touch with the White Fathers of Juvisy who were preparing to found the weekly Sept.

« I was courted a little by these fathers, who saw in me a neophyte animated by young and sparkling ideas. So I began by writing a sort of somewhat autobiographical novel, Histoires de grand dadais, and I sent the first chapters to them for reading. They were immediately published in the magazine and, very quickly, I was shown that I was at home, that I could do what I wanted. Being in Anduze had not closed my eyes at all and I naturally continued to keep myself informed of what was happening in the world. In response to an intervention by Mussolini in the Italian parliament following the invasion of Ethiopia by his armies – an intervention during which he had spat on France and the League of Nations – I responded as a poet, writing a dialogue that I entitled Force mauvaise, which recounted a meeting between Hitler and Mussolini during which they discussed the fate of Europe. Text accompanied by the photomontage of this meeting.»

↑

Michel Seuphor

Un siècle de liberté

1996Michel Seuphor’s text thus appeared in the magazine Sept, a visionary text that showed clearly, for those who cared to read, that everything was predictable: the demonstrations of 1934, the Crystal Night, in short, everything that was already contained in Mein Kampf, which Seuphor had read the year before. Having already experienced nationalism with the Fleming in Antwerp, he understood the motives and rhetoric, and felt that his experience made him responsible for speaking out. Unfortunately, nationalist and extremist ideas gained ground very quickly. Corréa, the publisher of his book Dans le royaume du coeur went back to Brazil and his work was taken over by the Buchet-Chastel publishing house. Seuphor was invited to lunch at the the home of this new publishers, who had just returned from Nuremberg, where they had attended a speech by Hitler, and he is appalled by their pro-nazis discourse.

In Anduze, the survival of the Seuphor couple was very difficult: « To try to round off our budget a little, and thanks to an excellent typewriter that had been offered to Suzanne, I decide to create a small magazine, La Nouvelle Campagne – typed thanks to Suzanne’s typing talent -, which earned us a few subscribers. This is what we lived on for five years. We also had a chicken coop, a piece of garden, but we needed some money for correspondence. The stamps to send out La Nouvelle Campagne were our biggest expense. And then, in June 1937, I learned from an issue of Sept and an accompanying letter that Rome was banning the magazine and forcing the Dominicans to declare that it was bankrupt, that it was not paying its way, and that, as a result, it had to stop publishing.»

Seuphor understood that this was an obligation to lie and soon learned that the deep reason was a decision of the Vatican, which the political positions of the magazine, especially its clearly anti-fascist articles, strongly displeased. « I therefore decided that my magazine La Nouvelle Campagne should take over from Sept, and I wrote a good number of articles against fascism and against Rome. The cessation of Sept was a terrible blow. I remained a Christian, but I left the Church.»

↑

Michel Seuphor,

Un siècle de liberté

1996The first issue of La Nouvelle Campagne dates from December 1934, the thirtieth and final issue is dated July 1939. Susanne Berckelaers-Seuphor told her granddaughter Sophie the memory of its production: « I used to insert up to seven carbons, my machine would not accept more and I had to retype the same text at least five times to reach the desired number of copies to send to our subscribers.»

La Nouvelle Campagne was a true object of connection and the vehicle of Michel Seuphor’s thought supported by his wife. The distribution was not easy and the couple had to remind, inside some issues, that the magazine has no other support than its selling price and the loyalty of the subscribers.

Each issue deals with various aspects of the author’s life and reflection with this unfailing openness towards the universal which allows him to put into abyss the thinnest subject of reflection: the birth of a flower, the grape harvest, politics, war, fear, treason, lies, poetry and its unique and primary place in the spirituality of everyone.

S. Berckelaers

LA NOUVELLE CAMPAGNE

In 1934, Michel Seuphor, through the intermediary of Jacques Maritain, came in touch with the White Fathers of Juvisy who were preparing to found the weekly Sept.

« I was courted a little by these fathers, who saw in me a neophyte animated by young and sparkling ideas. So I began by writing a sort of somewhat autobiographical novel, Histoires de grand dadais, and I sent the first chapters to them for reading. They were immediately published in the magazine and, very quickly, I was shown that I was at home, that I could do what I wanted. Being in Anduze had not closed my eyes at all and I naturally continued to keep myself informed of what was happening in the world. In response to an intervention by Mussolini in the Italian parliament following the invasion of Ethiopia by his armies – an intervention during which he had spat on France and the League of Nations – I responded as a poet, writing a dialogue that I entitled Force mauvaise, which recounted a meeting between Hitler and Mussolini during which they discussed the fate of Europe. Text accompanied by the photomontage of this meeting.»

↑

Michel Seuphor,

Un siècle de liberté

1996

Michel Seuphor’s text thus appeared in the magazine Sept, a visionary text that showed clearly, for those who cared to read, that everything was predictable: the demonstrations of 1934, the Crystal Night, in short, everything that was already contained in Mein Kampf, which Seuphor had read the year before. Having already experienced nationalism with the Fleming in Antwerp, he understood the motives and rhetoric, and felt that his experience made him responsible for speaking out. Unfortunately, nationalist and extremist ideas gained ground very quickly. Corréa, the publisher of his book Dans le royaume du coeur went back to Brazil and his work was taken over by the Buchet-Chastel publishing house. Seuphor was invited to lunch at the the home of this new publishers, who had just returned from Nuremberg, where they had attended a speech by Hitler, and he is appalled by their pro-nazis discourse.

In Anduze, the survival of the Seuphor couple was very difficult: « To try to round off our budget a little, and thanks to an excellent typewriter that had been offered to Suzanne, I decide to create a small magazine, La Nouvelle Campagne – typed thanks to Suzanne’s typing talent -, which earned us a few subscribers. This is what we lived on for five years. We also had a chicken coop, a piece of garden, but we needed some money for correspondence. The stamps to send out La Nouvelle Campagne were our biggest expense. And then, in June 1937, I learned from an issue of Sept and an accompanying letter that Rome was banning the magazine and forcing the Dominicans to declare that it was bankrupt, that it was not paying its way, and that, as a result, it had to stop publishing.»

Seuphor understood that this was an obligation to lie and soon learned that the deep reason was a decision of the Vatican, which the political positions of the magazine, especially its clearly anti-fascist articles, strongly displeased. « I therefore decided that my magazine La Nouvelle Campagne should take over from Sept, and I wrote a good number of articles against fascism and against Rome. The cessation of Sept was a terrible blow. I remained a Christian, but I left the Church.»

↑

Michel Seuphor,

Un siècle de liberté

1996

The first issue of La Nouvelle Campagne dates from December 1934, the thirtieth and final issue is dated July 1939. Susanne Berckelaers-Seuphor told her granddaughter Sophie the memory of its production: « I used to insert up to seven carbons, my machine would not accept more and I had to retype the same text at least five times to reach the desired number of copies to send to our subscribers.»

La Nouvelle Campagne was a true object of connection and the vehicle of Michel Seuphor’s thought supported by his wife. The distribution was not easy and the couple had to remind, inside some issues, that the magazine has no other support than its selling price and the loyalty of the subscribers.

Each issue deals with various aspects of the author’s life and reflection with this unfailing openness towards the universal which allows him to put into abyss the thinnest subject of reflection: the birth of a flower, the grape harvest, politics, war, fear, treason, lies, poetry and its unique and primary place in the spirituality of everyone.

S. Berckelaers

↑

La Nouvelle Campagne

n° VI, juillet 1935