NOVELS

NOVELS

Michel Seuphor’s five novels, which have a strong autobiographical content, bear witness to the author’s commitments and aspirations as well as to his inner transformations through contact with the rural world. His life experiences are both terrible and transcendent for the poet, in this period covering the Second World War. Facing death, disillusionment with the church, they testify to his unconditional quest for an ever-hard-won freedom to think and act according to his conscience. Through the portraits of the main characters, with whom he identifies himself, his conscience widens and deepens from novel to novel.

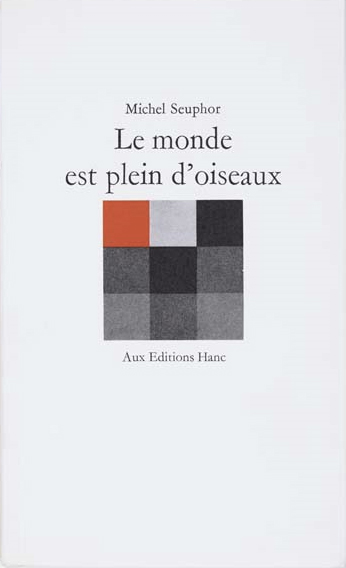

His last novel, Le monde est plein d’oiseaux (The World is Full of Birds), leaves the novelistic form as one leaves an era to blossom, in his own way, in a style that merges fable, philosophical and moralist thoughts with with poetry. The character of Calf, who appears for the first time in this novel, is the heart of it.

Sophie Berckelaers

Michel Seuphor’s five novels, which have a strong autobiographical content, bear witness to the author’s commitments and aspirations as well as to his inner transformations through contact with the rural world. His life experiences are both terrible and transcendent for the poet, in this period covering the Second World War. Facing death, disillusionment with the church, they testify to his unconditional quest for an ever-hard-won freedom to think and act according to his conscience. Through the portraits of the main characters, with whom he identifies himself, his conscience widens and deepens from novel to novel.

His last novel, Le monde est plein d’oiseaux (The World is Full of Birds), leaves the novelistic form as one leaves an era to blossom, in his own way, in a style that merges fable, philosophical and moralist thoughts with with poetry. The character of Calf, who appears for the first time in this novel, is the heart of it.

Sophie Berckelaers

•

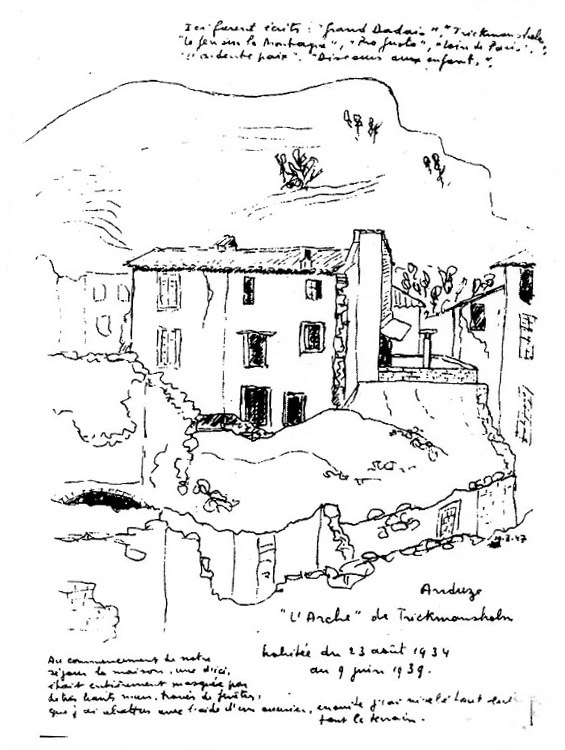

House of the ruins in Anduze, inhabited by the Seuphors from 1934 to 1939

•

Maison Claire, inhabited by the Seuphors from 1939 to 1945

•

Maison des ruines à Anduze, habitée par les Seuphor de 1934 à 1939

•

Maison Claire, habitée par les Seuphor de 1939 à 1945

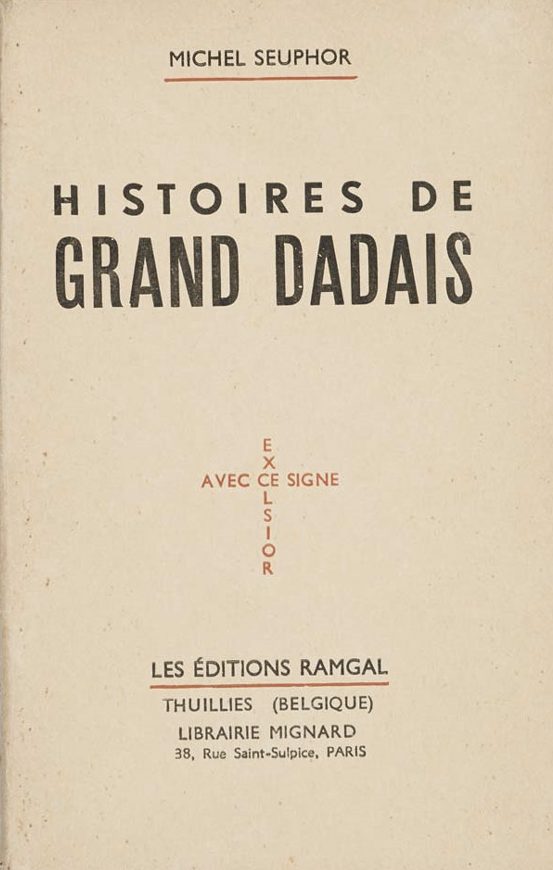

HISTOIRES DE GRAND DADAIS (STORIES OF A BIG KID)

Michel Seuphor, 1938 edition (the manuscript was written in Anduze from June 1935 to October 1936)

The author, best known as a poet and essayist, ventures here for the first time into the narrative genre.

… The youthful simplicity of the writing and of the thought is a characteristic of Michel Seuphor, of whom it has been said that he « abundantly possesses the gift of childhood, which is at the same time freshness of soul, alacrity of heart and generosity of spirit» …

Those who have enjoyed Seuphor’s other works will have the joy of finding here, in a particularly lively form, all the favorite themes of the writer: the cult of poverty, the love of nature, the exalting effusion of faith, the gift of self without measure.

…

Grand dadais can and must be in all hands. Those who understand him will not cease to love him more and more, because they will discover in him the friend of the most intimate of their hearts, the liberator of their most secret and purest capacity for love.

« I am your master,» says Grand Dadais himself at the beginning of the book, « and it is only me that you need. And why is that? Because I am only a child, but a child who speaks and who speaks to you, a child who is not afraid of blows. »

So Grand Dadais will pay with his life in a tragic final act that is also, and in the full sense of the word, an apotheosis.

↑

Press excerpts released at the time of the first publication in 1938

HISTOIRES DE GRAND DADAIS (STORIES OF A BIG KID)

Michel Seuphor, 1938 edition (the manuscript was written in Anduze from June 1935 to October 1936)

The author, best known as a poet and essayist, ventures here for the first time into the narrative genre.

… The youthful simplicity of the writing and of the thought is a characteristic of Michel Seuphor, of whom it has been said that he « abundantly possesses the gift of childhood, which is at the same time freshness of soul, alacrity of heart and generosity of spirit» …

Those who have enjoyed Seuphor’s other works will have the joy of finding here, in a particularly lively form, all the favorite themes of the writer: the cult of poverty, the love of nature, the exalting effusion of faith, the gift of self without measure.

…

Grand dadais can and must be in all hands. Those who understand him will not cease to love him more and more, because they will discover in him the friend of the most intimate of their hearts, the liberator of their most secret and purest capacity for love.

« I am your master,» says Grand Dadais himself at the beginning of the book, « and it is only me that you need. And why is that? Because I am only a child, but a child who speaks and who speaks to you, a child who is not afraid of blows. »

So Grand Dadais will pay with his life in a tragic final act that is also, and in the full sense of the word, an apotheosis.

↑

Press excerpts released at the time of the first publication in 1938

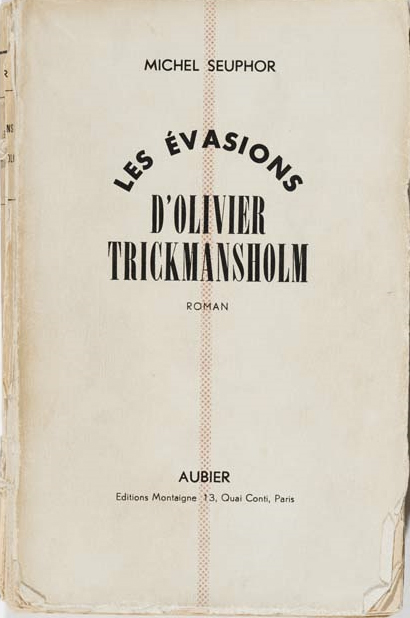

LES ÉVASIONS D’OLIVIER TRICKMANSHOLM (THE ESCAPES OF OLIVIER TRICKMANSHOLM)

The writing of the novel told by Michel Seuphor:

« In October 1937, thunder sounded in the serene sky under which I lived. The weekly Sept, which was doing well and was an excellent business, received the order from Rome to stop publishing for financial reasons. It was a terrible shock for me. The highest Catholic authority was blithely handling lies. At the same time, my livelihood and my confidence in the Church sank instantly. It was very serious, Suzanne could tell it better than me. I stayed ten days alone, locked in a room, without speaking, without even seeing her. The only thing I did was to go downstairs to collect dead leaves, to bring them in a bag upstairs, to burn them in the hearth (…)

My wife used to bring me my meals in my room. She thought I was crazy. After ten days, I said: « I found the word» . She thought I was really sick. « What word, my dear?” The word escape and I added « take the tray back, I’m coming down. I’ll eat with you and the kid”. When she saw me at the table, she noticed that I was normal. Immediately, I started to write the book that would be called Les évasions d’Olivier Trickmansholm. I wrote very quickly, abundantly, a manuscript that was immediately finalized, whereas others were sometimes redone, recast five or six times. It was published just before the declaration of war, by Aubier at the Montaigne publishing house. One day, Aubier sent me a telegram to Anduze, inviting me to a lunch offered to the members of the Goncourt Academy. « The case is in the bag!” We had the Goncourt for Les évasions d’Olivier Trickmansholm. I borrowed money and went to Paris. I had a lovely lunch in Aubier’s apartment, rue de Fleurus, with five or six members of the Goncourt Academy. Then, in the next room, a very witty and pleasant conversation. The deal was done!

A few days later, war was declared, and the Goncourt prize was postponed. Fernand Aubier had decided that there would be no war, because he didn’t want it. He became furious and dropped everything. As for me, I didn’t care, it seemed to me that there had been a misunderstanding. The Goncourt could not be for me. I am, to this day, glad I didn’t get it, because it would have steered my life in a different direction.»

↑

Michel Seuphor, Une vie à angle droit

Éditions de la Différence, 1988, p 77LES ÉVASIONS D’OLIVIER TRICKMANSHOLM (THE ESCAPES OF OLIVIER TRICKMANSHOLM)

The writing of the novel told by Michel Seuphor:

« In October 1937, thunder sounded in the serene sky under which I lived. The weekly Sept, which was doing well and was an excellent business, received the order from Rome to stop publishing for financial reasons. It was a terrible shock for me. The highest Catholic authority was blithely handling lies. At the same time, my livelihood and my confidence in the Church sank instantly. It was very serious, Suzanne could tell it better than me. I stayed ten days alone, locked in a room, without speaking, without even seeing her. The only thing I did was to go downstairs to collect dead leaves, to bring them in a bag upstairs, to burn them in the hearth (…)

My wife used to bring me my meals in my room. She thought I was crazy. After ten days, I said: « I found the word» . She thought I was really sick. « What word, my dear?” The word escape and I added « take the tray back, I’m coming down. I’ll eat with you and the kid”. When she saw me at the table, she noticed that I was normal. Immediately, I started to write the book that would be called Les évasions d’Olivier Trickmansholm. I wrote very quickly, abundantly, a manuscript that was immediately finalized, whereas others were sometimes redone, recast five or six times. It was published just before the declaration of war, by Aubier at the Montaigne publishing house. One day, Aubier sent me a telegram to Anduze, inviting me to a lunch offered to the members of the Goncourt Academy. « The case is in the bag!” We had the Goncourt for Les évasions d’Olivier Trickmansholm. I borrowed money and went to Paris. I had a lovely lunch in Aubier’s apartment, rue de Fleurus, with five or six members of the Goncourt Academy. Then, in the next room, a very witty and pleasant conversation. The deal was done!

A few days later, war was declared, and the Goncourt prize was postponed. Fernand Aubier had decided that there would be no war, because he didn’t want it. He became furious and dropped everything. As for me, I didn’t care, it seemed to me that there had been a misunderstanding. The Goncourt could not be for me. I am, to this day, glad I didn’t get it, because it would have steered my life in a different direction.»

↑

Michel Seuphor, Une vie à angle droit

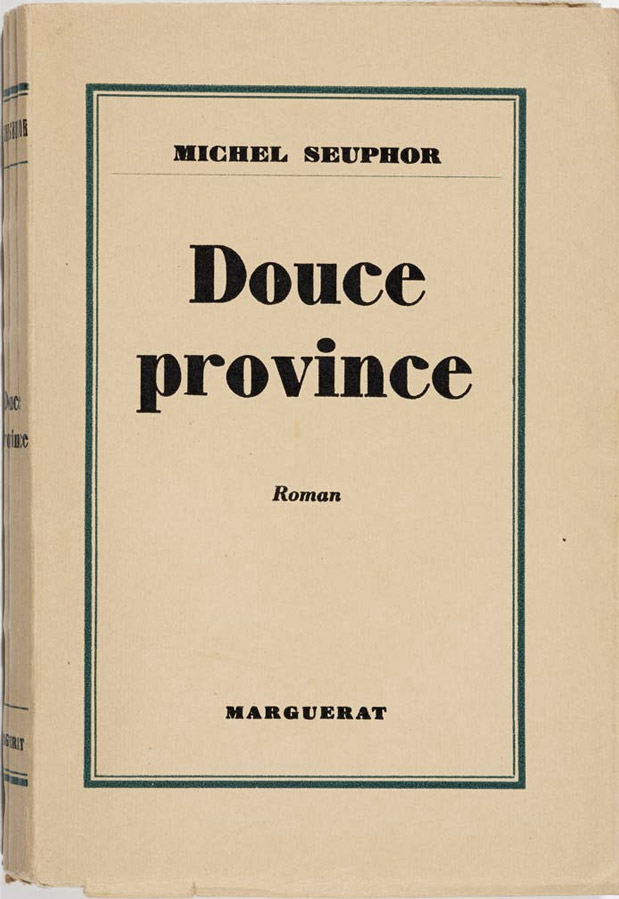

Éditions de la Différence, 1988, p 77DOUCE PROVINCE (SWEET PROVINCE)

Press extracts published in 1941

• What art in the touch! What penetration under the apparent nonchalance of the tone; what religious concern also, free of all literature. (Jean Nicollier, Gazette de Lausanne).

• A beautiful novel and a precious human document… The work ends on the eve of the war we are living, but it goes beyond the framework of time (Express).

• It is about the soul of France. The province only lends its name, or, to put it better, it is the quiet cell where this soul seeks and recognizes itself… A great debate on the eve of great events (Neue Zürcher Zeitung).

• An extremely profound and moving work, a work that is poignant with life and anguish, tragic because of the constant duel between the intelligence and the heart, and which ends with a sublime cry of faith that makes one think of Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis in D, springing from the darkness of the burial (Revue de Lausanne).

• Michel Seuphor reveals himself with Douce Province as the one of all the young writers of today who best represents the contemporary demand for an authentic spiritual rebirth (Le Mémorial).

• All the debates that have fascinated us have their echo here, contemporary France vibrates with all its soul. And through the painting of the most diverse types, one dominates: this hard conquest, of a fidelity to the spirit. This is not only a beautiful book and an authentic testimony, but also a tribute to the pure energy of the heart (Henri Lemaitre, Positions)

DOUCE PROVINCE (SWEET PROVINCE)

Press extracts published in 1941

• What art in the touch! What penetration under the apparent nonchalance of the tone; what religious concern also, free of all literature. (Jean Nicollier, Gazette de Lausanne).

• A beautiful novel and a precious human document… The work ends on the eve of the war we are living, but it goes beyond the framework of time (Express).

• It is about the soul of France. The province only lends its name, or, to put it better, it is the quiet cell where this soul seeks and recognizes itself… A great debate on the eve of great events (Neue Zürcher Zeitung).

• An extremely profound and moving work, a work that is poignant with life and anguish, tragic because of the constant duel between the intelligence and the heart, and which ends with a sublime cry of faith that makes one think of Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis in D, springing from the darkness of the burial (Revue de Lausanne).

• Michel Seuphor reveals himself with Douce Province as the one of all the young writers of today who best represents the contemporary demand for an authentic spiritual rebirth (Le Mémorial).

• All the debates that have fascinated us have their echo here, contemporary France vibrates with all its soul. And through the painting of the most diverse types, one dominates: this hard conquest, of a fidelity to the spirit. This is not only a beautiful book and an authentic testimony, but also a tribute to the pure energy of the heart (Henri Lemaitre, Positions)

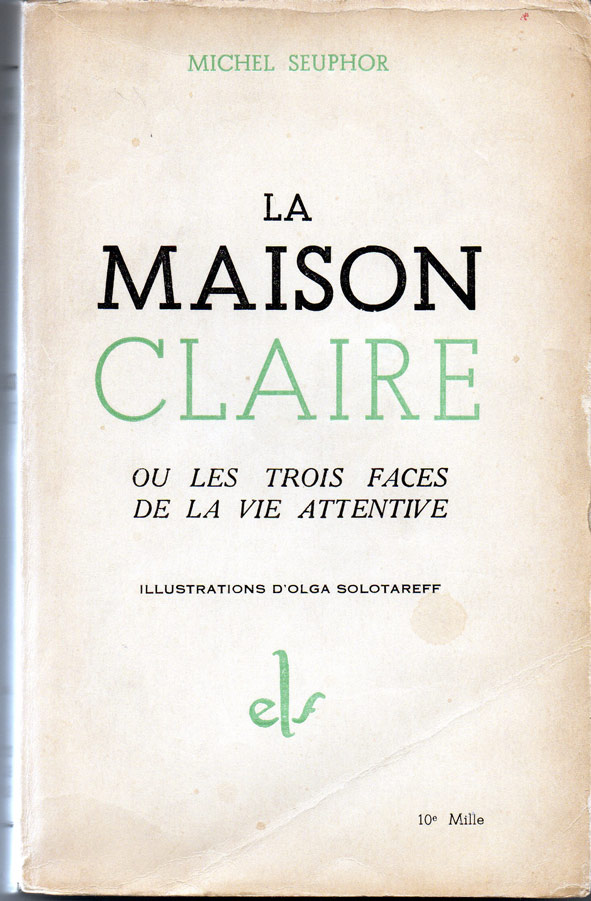

LA MAISON CLAIRE OU LES TROIS FACES DE LA VIE ATTENTIVE (THE MAISON CLAIRE OR THE THREE FACES OF ATTENTIVE LIVING)

Excerpt

THE WORD

« The word is first of all a cry. A wild cry of fear, of love, of admiration, of hate. By clinging to the mane, we ride it, then we tame it little by little. Don’t be satisfied with the manes: put A bridle to your cry, you will go straight, you will go far. But let the cry remain a cry, let its strength remain and its ardor, and its passion to run. There are writers who are at ease, who ride in a phaeton, an omnibus, a tilbury, and who only go out in good weather. There are even some who have a whole stable of old wisdom always dressed up, and a coachman and A footmen. They have nothing to say and kill the divine time. The world rewards them royally with the rentier virtues they cultivate, for their murder. But life is running out there that their lazy eye can no longer follow, can no longer even see, and the cry, to their blocked ears, is a very negligible murmur, a naïve stammering (go beg elsewhere!). And sometimes that whisper buries them before they are dead.»

Press excerpts released at the time of publication in 1943

• This book is a masterpiece. It is, in the old and full sense of the word; it is the work of a man in full possession of his means, it is the work exactly carried out, in its framework and the aimed goal; it is, humanly speaking, seen and said perfectly (André Druelle)

• The work of Michel Seuphor touches the heart and the mind. I said that it should be received as a testimony. And well! It is a testimony of the most complete sincerity, poignant, harsh, the testimony of a Christian in the century, saving his soul by losing it according to the rigor of the evangelical precept, rowing against the century, hanging on to the Cross and participating in its scandal: such as it is (Luc Estang, La Croix).

LA MAISON CLAIRE OU LES TROIS FACES DE LA VIE ATTENTIVE (THE MAISON CLAIRE OR THE THREE FACES OF ATTENTIVE LIVING)

Excerpt

THE WORD

« The word is first of all a cry. A wild cry of fear, of love, of admiration, of hate. By clinging to the mane, we ride it, then we tame it little by little. Don’t be satisfied with the manes: put A bridle to your cry, you will go straight, you will go far. But let the cry remain a cry, let its strength remain and its ardor, and its passion to run. There are writers who are at ease, who ride in a phaeton, an omnibus, a tilbury, and who only go out in good weather. There are even some who have a whole stable of old wisdom always dressed up, and a coachman and A footmen. They have nothing to say and kill the divine time. The world rewards them royally with the rentier virtues they cultivate, for their murder. But life is running out there that their lazy eye can no longer follow, can no longer even see, and the cry, to their blocked ears, is a very negligible murmur, a naïve stammering (go beg elsewhere!). And sometimes that whisper buries them before they are dead.»

Press excerpts released at the time of publication in 1943

• This book is a masterpiece. It is, in the old and full sense of the word; it is the work of a man in full possession of his means, it is the work exactly carried out, in its framework and the aimed goal; it is, humanly speaking, seen and said perfectly (André Druelle)

• The work of Michel Seuphor touches the heart and the mind. I said that it should be received as a testimony. And well! It is a testimony of the most complete sincerity, poignant, harsh, the testimony of a Christian in the century, saving his soul by losing it according to the rigor of the evangelical precept, rowing against the century, hanging on to the Cross and participating in its scandal: such as it is (Luc Estang, La Croix).

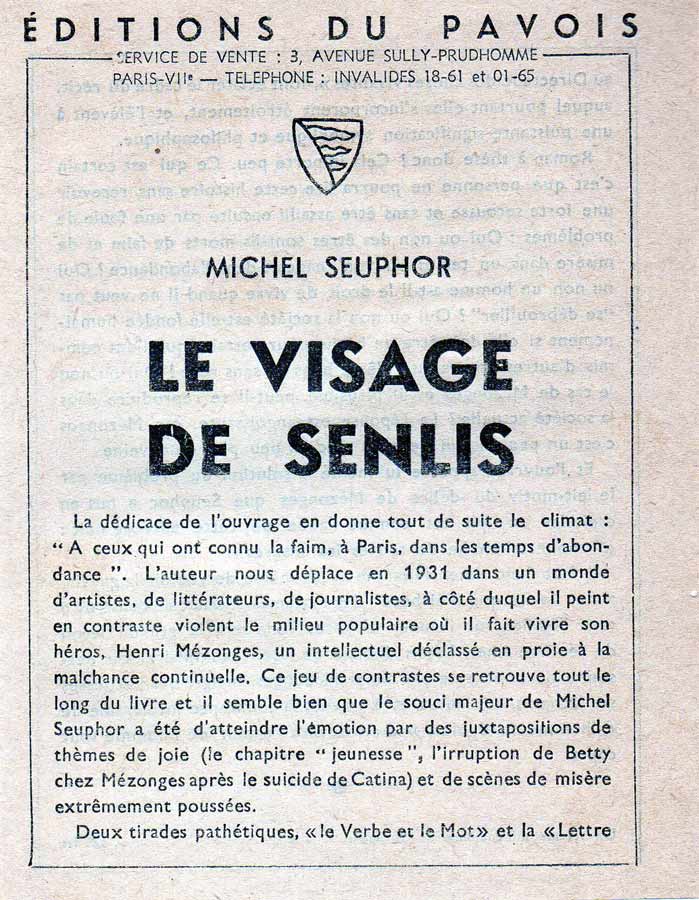

LE VISAGE DE SENLIS (THE FACE OF SENLIS)

Publisher’s announcement

The dedication of the book immediately sets the mood: « to those who have known hunger, in Paris, in times of abundance» . In 1931, the author takes us to a world of artists, writers, and journalists, alongside which he paints a violent contrast with the working-class environment in which his hero, Henri Mézonges, a downtrodden intellectual plagued by constant misfortune, lives. This play of contrasts is found throughout the book and it seems that Michel Seuphor’s main concern was to achieve emotion through juxtapositions of themes of joy and scenes of extreme misery.

Two pathetic tirades, « the verb and the word» and the « letter to the director of living things» , burst the framework of the story, even if they are closely incorporated to it, and raise it to a powerful symbolic and philosophical meaning.

Is this a thesis novel? It does not matter. What is certain is that no one will be able to read this story without receiving a strong jolt and without being assailed afterwards by a host of problems: yes or no, did beings die of hunger and misery in a time when « we» were swimming in abundance? Yes or no, does a man have the right to live when he does not want to « manage» ?

Yes or no, is society humanly founded if it is to be a prison for some who have committed no other crime than being good and guileless? Is the case of Mézonges plausible, can it happen again in today’s society? The answer is frightening, because Mezonges is a little bit of each of us with a little bit more mischief. And the book itself brings the solution of the problem by the leitmotiv of Mézonges’ delirium that Seuphor has put in capital and which is like the dawn of this awful night where : « love triumphs over all miseries» .

It is therefore necessary to love man even before wanting to cure him, to love before elaborating social systems and to build the edifice on love first. This is the great lesson of this bitter book. A lesson given in an exemplary way, because no one can fail to love Mézonges, despite his pettiness and cowardice, his faults, and through the intolerable suffering of the « man of pain» we will find the love of man himself.

196 pages. 129 Frs.

LE VISAGE DE SENLIS (THE FACE OF SENLIS)

Publisher’s announcement

The dedication of the book immediately sets the mood: « to those who have known hunger, in Paris, in times of abundance» . In 1931, the author takes us to a world of artists, writers, and journalists, alongside which he paints a violent contrast with the working-class environment in which his hero, Henri Mézonges, a downtrodden intellectual plagued by constant misfortune, lives. This play of contrasts is found throughout the book and it seems that Michel Seuphor’s main concern was to achieve emotion through juxtapositions of themes of joy and scenes of extreme misery.

Two pathetic tirades, « the verb and the word» and the « letter to the director of living things» , burst the framework of the story, even if they are closely incorporated to it, and raise it to a powerful symbolic and philosophical meaning.

Is this a thesis novel? It does not matter. What is certain is that no one will be able to read this story without receiving a strong jolt and without being assailed afterwards by a host of problems: yes or no, did beings die of hunger and misery in a time when « we» were swimming in abundance? Yes or no, does a man have the right to live when he does not want to « manage» ?

Yes or no, is society humanly founded if it is to be a prison for some who have committed no other crime than being good and guileless? Is the case of Mézonges plausible, can it happen again in today’s society? The answer is frightening, because Mezonges is a little bit of each of us with a little bit more mischief. And the book itself brings the solution of the problem by the leitmotiv of Mézonges’ delirium that Seuphor has put in capital and which is like the dawn of this awful night where : « love triumphs over all miseries» .

It is therefore necessary to love man even before wanting to cure him, to love before elaborating social systems and to build the edifice on love first. This is the great lesson of this bitter book. A lesson given in an exemplary way, because no one can fail to love Mézonges, despite his pettiness and cowardice, his faults, and through the intolerable suffering of the « man of pain» we will find the love of man himself.

196 pages. 129 Frs.

LE MONDE EST PLEIN D’OISEAUX (THE WORLD IS FULL OF BIRDS)

Excerpt

« – What do I feel? Well, that, old Calf, something there in me that is also something alive in the world, alive is not the word: a presence more than life, in us, in all beings, something that pushes us and drags us, something that walks with us, that we cannot know, for sure, as I see you and know you, but that is there anyway, that we can feel. Have you ever felt that?

-Yes, Calf said gently. The antennae of the mind.

-No, but nothing intellectual at first, Rammegoux continued, excited by his ideas. That comes after. Thinking comes after feeling. One feels like the presence of something. When I look at a tree, look, one of the trees in the square, through the window, sometimes it speaks to me, there is something between the tree and me, and I can look at it for hours without thinking about anything and without getting tired of looking, and it’s as if I were listening to something, a music, a secret dialogue, what do I know, but there is something that I feel very well, a contact between the tree and me. I can’t say what it is, but something is happening between this tree and me, I feel something that is common between it and me, the presence of a being. Does this escape you?

-No, oh, but not at all,» said Calf, more and more intimidated by this simplicity, by this revelation of inner life that he had not expected.»

LE MONDE EST PLEIN D’OISEAUX (THE WORLD IS FULL OF BIRDS)

Excerpt

« – What do I feel? Well, that, old Calf, something there in me that is also something alive in the world, alive is not the word: a presence more than life, in us, in all beings, something that pushes us and drags us, something that walks with us, that we cannot know, for sure, as I see you and know you, but that is there anyway, that we can feel. Have you ever felt that?

-Yes, Calf said gently. The antennae of the mind.

-No, but nothing intellectual at first, Rammegoux continued, excited by his ideas. That comes after. Thinking comes after feeling. One feels like the presence of something. When I look at a tree, look, one of the trees in the square, through the window, sometimes it speaks to me, there is something between the tree and me, and I can look at it for hours without thinking about anything and without getting tired of looking, and it’s as if I were listening to something, a music, a secret dialogue, what do I know, but there is something that I feel very well, a contact between the tree and me. I can’t say what it is, but something is happening between this tree and me, I feel something that is common between it and me, the presence of a being. Does this escape you?

-No, oh, but not at all,» said Calf, more and more intimidated by this simplicity, by this revelation of inner life that he had not expected.»